Photos: The Amazing Animals of China

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

China is home to some amazing animal species, from golden snub-nose monkeys to the charismatic giant panda. New research suggests that protections given to the bamboo-eating pandas have benefited other threatened species in the region. Here's a look at China's gorgeous wildlife. [Read the full story on how panda protections help other species]

Protection for one, protection for many

A golden snub-nose monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana), found only in the forest of central and southwestern China. New research published September 16 in the journal Conservation Biology finds that these endangered monkeys can benefit from protections meant for pandas. Panda preserves provide an "umbrella" of protection for golden snub-nose monkeys and other species that share the panda's range. This monkey is seen in the Qinling Mountains of Shaanxi Province. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Endangered cuties

Golden snub-nose monkeys live in bands of dozens to hundreds in forests between 4,900 feet and more than 11,000 feet (1,500 meters to 3,400 meters) elevation, and they're adapted for the cold, snowy weather found at these heights. They are listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). According to the IUCN, there are a total of about 20,000 golden snub-nose monkeys (divided among three subspecies) in the wild. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Safe havens

Panda and golden snub-nose monkey habitat overlaps, meaning that panda preserves provide zones of safety for these monkeys. Habitat destruction is the main threat to these monkeys, according to the University of Wisconsin's Primate Info Net, though poaching for fur and meat remains a concern, too. This monkey was photographed in the Qinling Mountains of Shaanxi Province. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Not endangered, but protected

A blue eared pheasant (Crossoptilon auritum) at the Wanglang National Nature Reserve in Sichuan Province. This nature reserve, established in 1965, protects giant pandas as well as these birds, which live in mountainous areas of central China. The blue eared pheasant is listed as "least concern" by the IUCN. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Fun and engaging, and protecting others

A panda plays peek-a-boo around a tree trunk at the Bifengxia Giant Panda Breeding and Conservation Center in Sichuan Province. China's flagship species provides an umbrella of protections for less charismatic animals. New research reveals that 96 percent of the panda's range is in "endemic centers" — areas that are in the top 5 percent for number of species found only in China. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Great care, time and money

A giant panda at the Bifengxia Giant Panda Breeding and Conservation Center in Sichuan Province. China has devoted large amounts of resources into protecting pandas, including a successful lending program that has seen these hard-to-breed bears reproduce in zoos around the world. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

A little known species

Pandas are iconic, but the takin (Budorcas taxicolor tibetana) is hardly known outside its range. This takin – a subspecies known as the Sichuan or Tibetan takin — stands in snow at the Wanglang National Nature Reserve. Takins are also known as gnu goats. This subspecies is listed as vulnerable by the IUCN. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Using available resources

A Sichuan takin scratches an itch at the Wanglang National Nature Reserve. Takin live alongside pandas, tackling steep slopes with ease and hiding in dense underbrush. They roam at elevations as lofty as 14,000 feet (4,267 m), according to the Lincoln Park Zoo. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Here's lookin' at you

The takin's large snout helps it warm the cold mountain air as it breathes, keeping the animal toasty even in the depths of winter. Takins also have thick, double-layered coats, according to the San Diego Zoo. Because takins live in such cold, remote climes, little is known about their numbers or behavior in the wild. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Kept safe in the preserve

Maroon-backed Accentor (Ptunella immaculata) has a large range throughout Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar and Nepal, according to the IUCN, which lists the bird as "least concern." This bird perches in the Wanglang National Nature Reserve in Sichuan, China. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

In their natural environment

Blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur) at the Wanglang National Nature Reserve. These animals are also known as bharal, or naur. Nimble slope-dwellers, blue sheep are the main food source of the elusive snow leopard, according to the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Center of attention

A blue-eared pheasant struts its stuff at the Wanglang National Nature Reserve in Sichuan, China. These birds grown nearly 3 feet (nearly 1 meter) long and sport a curved tail of two dozen feathers. They live in the high forests of Sichuan, Tibet and Gansu province. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

In need of a protector

A Tibetan Macaque (Macaca thibetana) photographed at Tangjiahe National Nature Reserve in Sichuan. This species, listed as near-threatened by the IUCN, is threatened by deforestation in east-Central China. Although this macaque is perching on a branch, these animals spend most of their time on the ground and sleep mostly in caves. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Protected beauty

A striking golden pheasant (Chrysolophus pictus) amidst greenery at Changqing National Nature Reserve in China's Shaanxi Province. Native to China, golden pheasants now live in as far-flung locations as the United States, New Zealand and Peru, transported by humans as game birds. Males sport showy red-and-yellow feathers, while female golden pheasants are duller brown. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Rock climbers protected

Blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur) at Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve in Qinghai Province, China. This nature reserve covers part of the Tibetan Plateau, where blue sheep roam in small herds. These ungulates can climb as high as 21,000 feet (6,500 m) on rocky slopes, according to the Snow Leopard Trust. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

Protection measures needed

A close-up of a Tibetan Macaque (Macaca thibetana) at the Tangjiahe National Nature Reserve in Sichuan, China. These monkeys range from eastern Tibet into southeastern China and are listed as near threatened by the IUCN. Forest loss and habitat destruction are this monkey's greatest threat. (Credit: Binbin Li.)

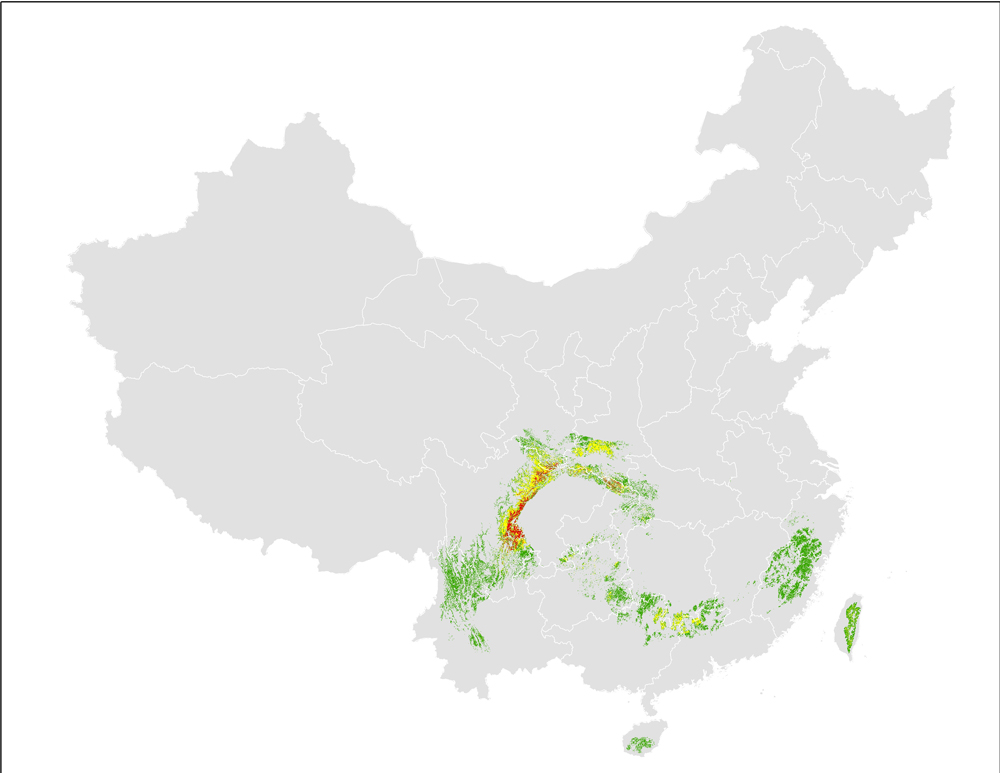

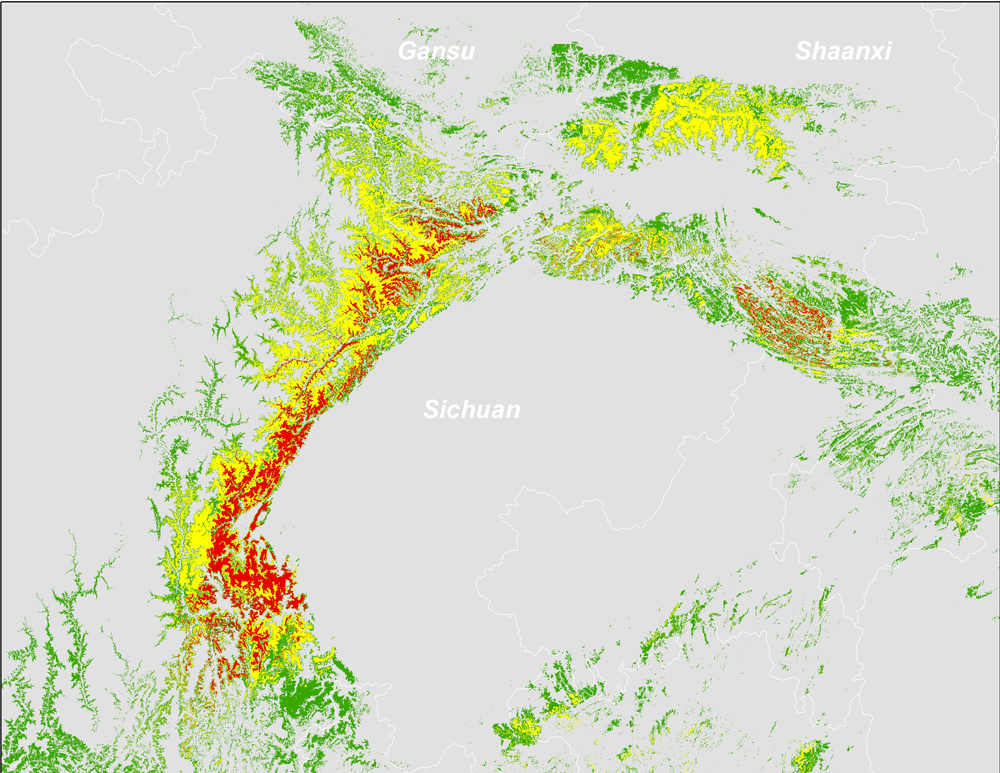

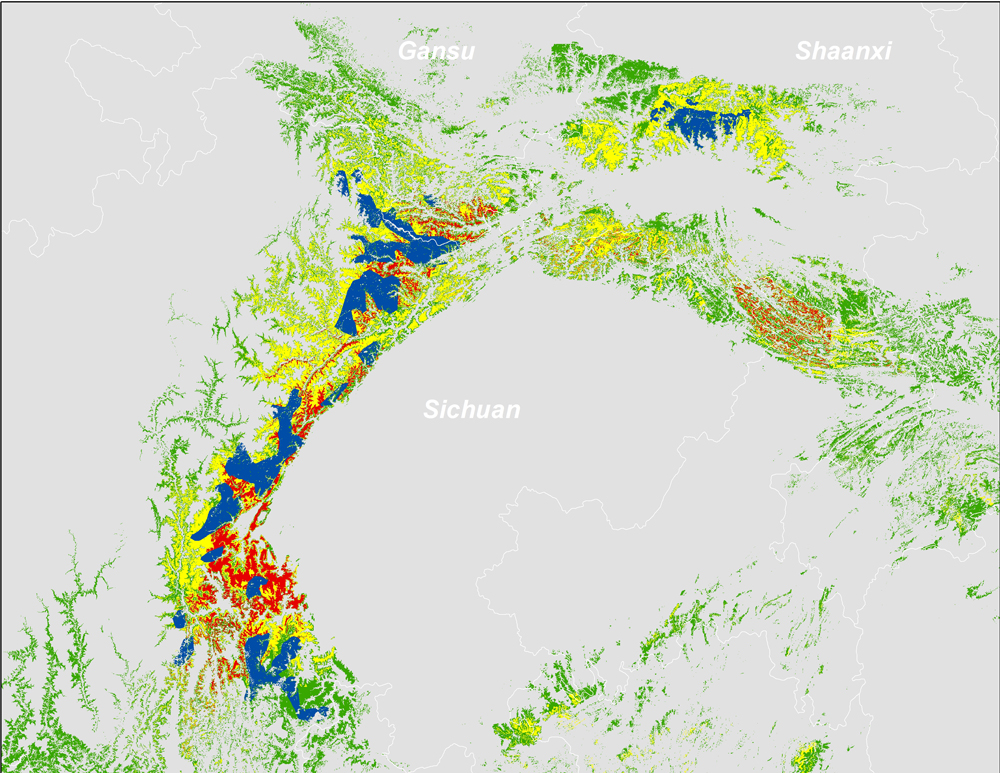

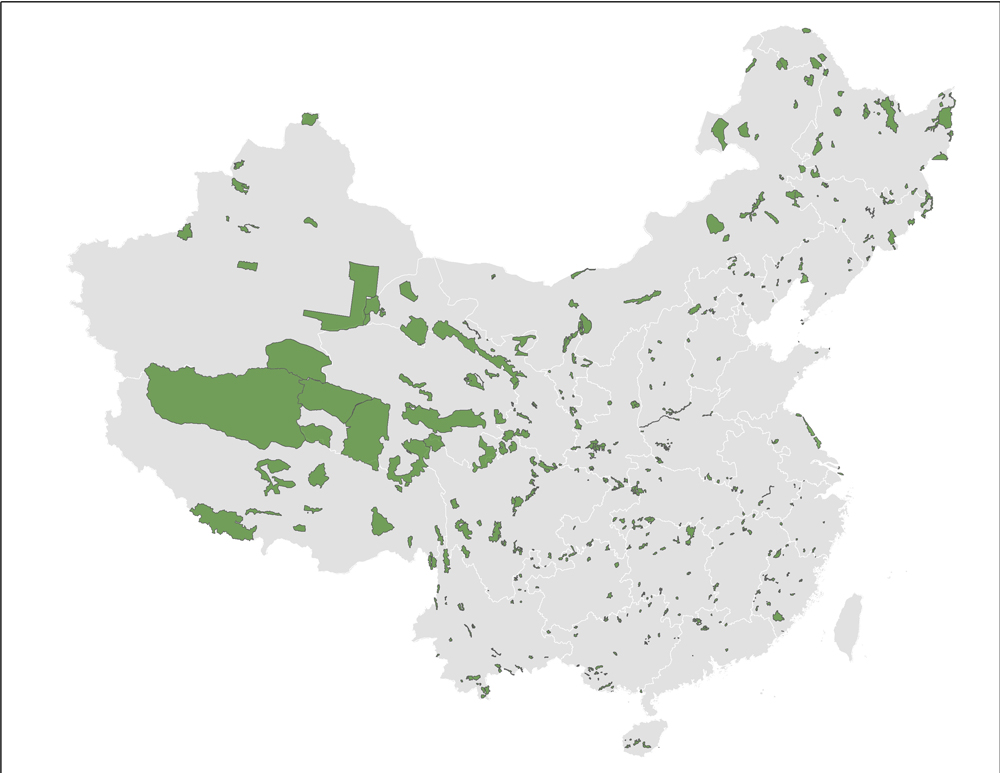

Home to unique species

A map of China showing "endemic centers," or the top 5 percent richest regions for species found only in China. Red areas are endemic centers for birds, mammals and amphibians; yellow areas are endemic centers for two of the tree. Blue areas are rich in one of the three groups. (Credit: Binbin Li & Stuart Pimm.)

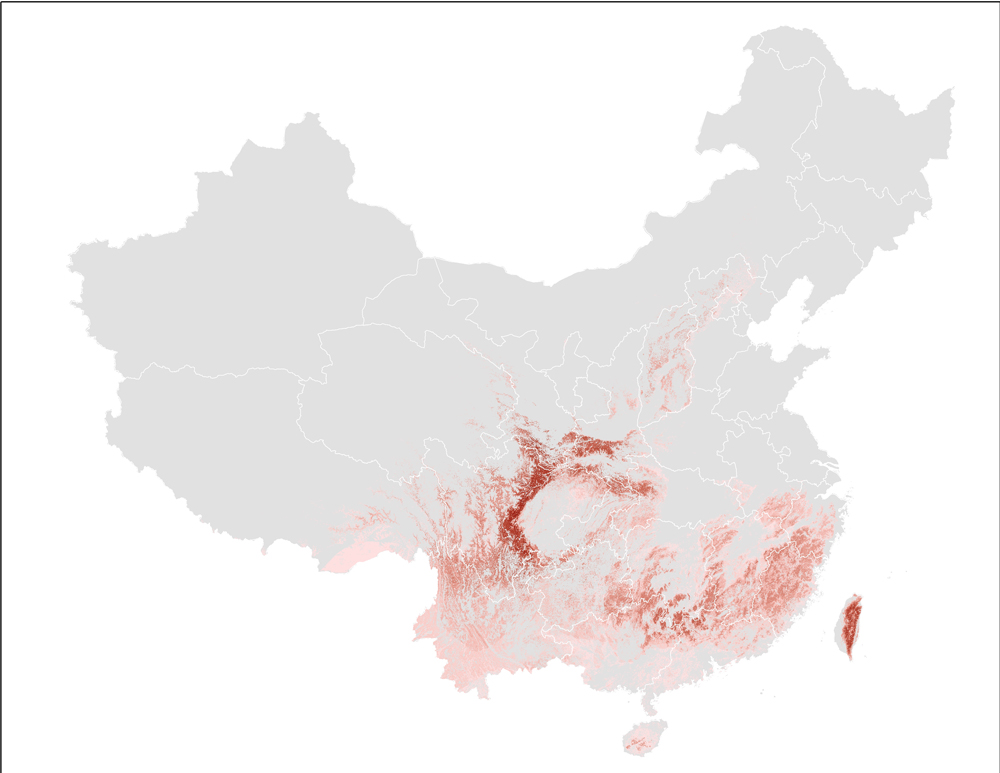

Protected by default

A map of endemic bird distribution in China. Darker areas represent spots where there are more species of birds unique to the country. Half of the endemic animals of China are forest species, which means their ranges often overlap with the range of giant pandas. (Credit: Binbin Li & Stuart Pimm.)

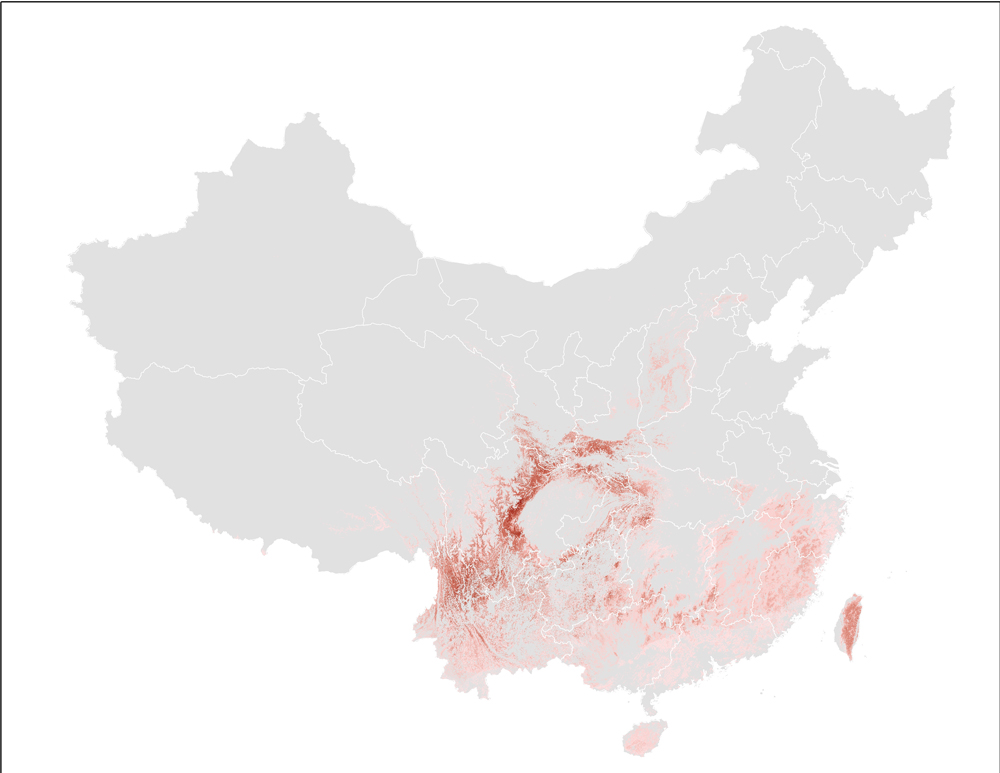

Diversity abounds, needs protection

A map of endemic mammal diversity in China. The darker the region, the more endemic species live there. Endemic species are defined as those whose range is more than 80 percent within China's borders. (Credit: Binbin Li & Stuart Pimm.)

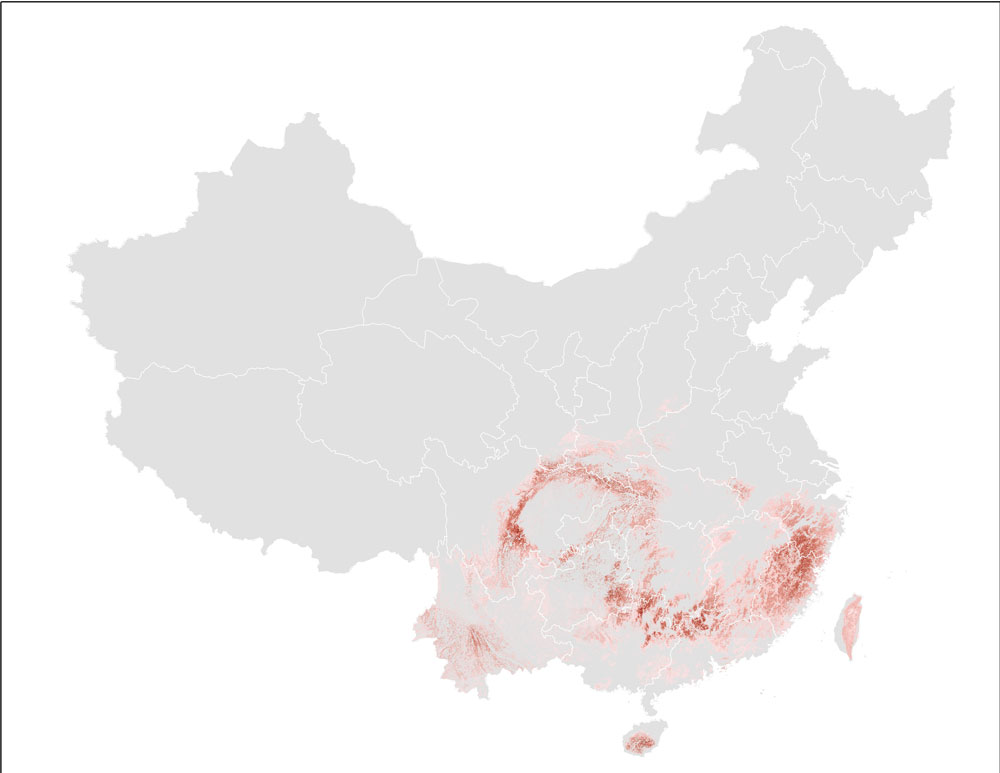

More protection needed

A map of endemic amphibian distribution across China. The darker the color, the more amphibian species unique to China live in the region. Amphibians are the group least protected by panda reserves; panda range overlaps with the range of only 31 percent of amphibian species, according to new research in the journal Conservation Biology. All told, 99 percent of small-range amphibians and 85 percent of large-range amphibians lack protection, the researchers found. (Credit: Binbin Li & Stuart Pimm.)

Staying put

A map showing the distribution of giant pandas in China. Pandas are mostly found in China's Sichuan province, subsisting on a diet of bamboo. (Credit: Binbin Li & Stuart Pimm.)

Additional protections for native animals

A close-up on the mountains of Sichuan, Gansu and Shaanxi provinces, where pandas are found. This map shows the number of endemic species in this region. Endemic species are defined as animals found entirely or almost entirely in China. Red areas are the top 5 percent for number of endemic species of birds, mammals and amphibians. Yellow areas are top 5 percent for two out of the three groups, while blue areas are top 5 percent in one of the three groups. (Credit: Binbin Li & Stuart Pimm.)

Natural homes

A map of endemic centers in the Sichuan region with panda protection areas overlaid in blue. This map shows places where panda reserves are protecting other native species. It also shows species-rich areas that are not protected. (Credit: Binbin Li & Stuart Pimm.)

Where the protection is

A map of China showing the distribution of national nature reserves in green. Reserves predominate in areas that are high, arid and sparsely populated; few are found along China's crowded eastern coast. (Credit: Binbin Li & Stuart Pimm.)

Unexpected benefits

The maps reveal that pandas are a boon for China's wildlife, and that further protection for pandas will end up benefitting other species as well. Currently, 14 mammal species, 20 bird species and 82 amphibian species are insufficiently protected. (Credit: Binbin Li & Stuart Pimm.)

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus