Oldest Medical Report of Near-Death Experience Discovered

Reports of people having "near-death" experiences go back to antiquity, but the oldest medical description of the phenomenon may come from a French physician around 1740, a researcher has found.

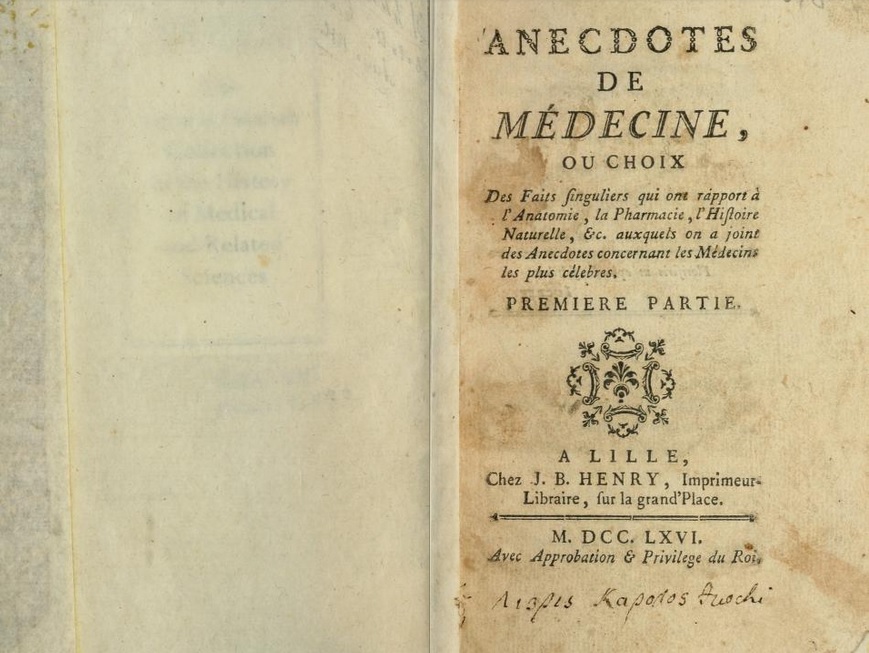

The report was written by Pierre-Jean du Monchaux, a military physician from northern France, who described a case of near-death experience in his book "Anecdotes de Médecine." Monchaux speculated that too much blood flow to the brain could explain the mystical feelings people report after coming back to consciousness.

The description was recently found by Dr. Phillippe Charlier, a medical doctor and archeologist, who is well known in France for his forensic work on the remains of historical figures. Charlier unexpectedly discovered the medical description in a book he had bought for 1 euro (a little more than $1) in an antique shop.

"I was just interested in the history of medicine, and medical practices in the past, especially during this period, the 18th century," Charlier told Live Science. "The book itself was not an important one in the history of medicine, but from a historian's point of view, the possibility of doing retrospective diagnosis on such books, it's something quite interesting."

To his surprise, Charlier found a modern description of near-death experience from a time in which most people relied on religion to explain near-death experiences. [The 10 Most Controversial Miracles]

The book describes the case of a patient, a famous apothecary (pharmacist) in Paris, who temporarily fell unconscious and then reported that he saw a light so pure and bright that he thought he must have been in heaven.

Today, near-death experience is described as a profound psychological event with transcendental and mystical elements that occurs after a life-threatening crisis, Charlier said. People who experience the phenomenon report vivid and emotional sensations including positive emotions, feeling as though they have left their bodies, a sensation of moving through a tunnel, and the experiences of communicating with light and meeting with deceased people.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Charlier compared the nearly 250-year-old description with today's "Greyson criteria," which is a scale that a psychiatrist developed in the 1980s to measure the depth of people's near-death experiences, so that these cases could be uniformly studied. The scale includes questions about the perceptions people report during near-death experiences, for example altered sense of time, life review and feelings of joy. A score of 7 or higher out of a possible 32 is classified as a near-death experience.

Although the data in the old book were limited, Charlier determined that the patient would have scored at least 12/32 on the Greyson criteria, Charlier said. He published his findings last month in the journal Resuscitation.

In the 18th-century case description, Monchaux also compared his patient with other people who reported similar experiences, caused by drowning, hypothermia and hanging.

The physician offered a medical explanation for the bizarre sensations, too, but his explanation was the opposite of what modern day physicians name as the likely cause of near-death experience, Charlier said. Monchaux speculated that in all of reported cases of near-death experience, the patients were left with little blood in the veins in their skin, and abundant blood flowing in the vessels within their brains, giving rise to the vivid and strong sensations.

However, modern researchers think it is likely the lack of blood flow and oxygen to the brain that puts the organ in a state of full alarm and causes the sensations associated with near-death experiences.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus