Wow! Natural Art in the Ocean

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

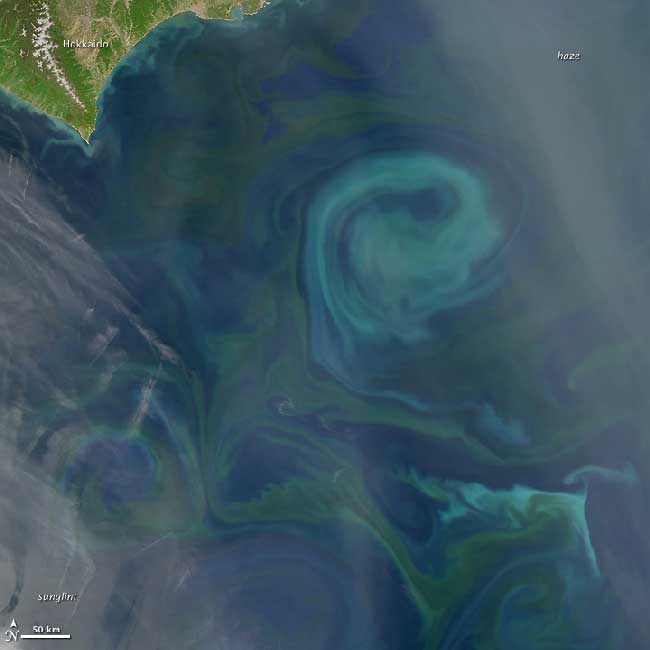

This photo, taken from a NASA satellite, reveals the life embedded in two ocean currents that are converging in the Pacific Ocean.

In the northwest Pacific, the Oyashio Current flows down out of the Arctic, past Siberia and the Kamchatka Peninsula. Around the latitude of Hokkaido, Japan, it begins to veer eastward and converges with the warmer Kuroshio Current, flowing into the area from the south.

The new image illustrates how the convergence of these two currents affects phytoplankton, the microscopic plant-like creatures that form the base of the marine food web, scientists explained.

When two currents with different temperatures and densities — cold, Arctic water is saltier and denser than subtropical waters — collide, they create eddies. Phytoplankton growing in the surface waters become concentrated along the boundaries of these eddies, tracing out the motions of the water. The swirls of color visible in the waters southeast of Hokkaido (upper left), show where different kinds of phytoplankton are using chlorophyll and other pigments to capture sunlight and produce food. The bright blues just offshore of Hokkaido may be churned up sediment, rather than phytoplankton.

During the spring bloom season, nutrients are abundant in the surface waters. The water has been "resting" all winter, when light levels were too low — and storms were too frequent — to support phytoplankton growth.

But as the phytoplankton deplete the available nutrients, the bloom will taper off. At this stage, the eddies in the convergence zone can give a boost of nutrients at the surface because they don't just circulate the surface water; they also produce upwelling. The upwelling can draw nutrient-rich water up from deeper in the ocean, allowing smaller blooms to occur later in the growing season.

The washed out appearance of the image at lower left is from sunglint—the (blurred) mirror-like reflection of the sun off the water. At upper right, a plume of haze, perhaps smoke from fires in Mongolia and Russia, cuts across the scene.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The image, from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Aqua satellite, was taken May 21 and released this week.

- Gallery: Earth as Art

- Planet Earth: A Year of Pictures

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus