Chasing Volcanoes with Filmmaker Bertrand Loyer

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

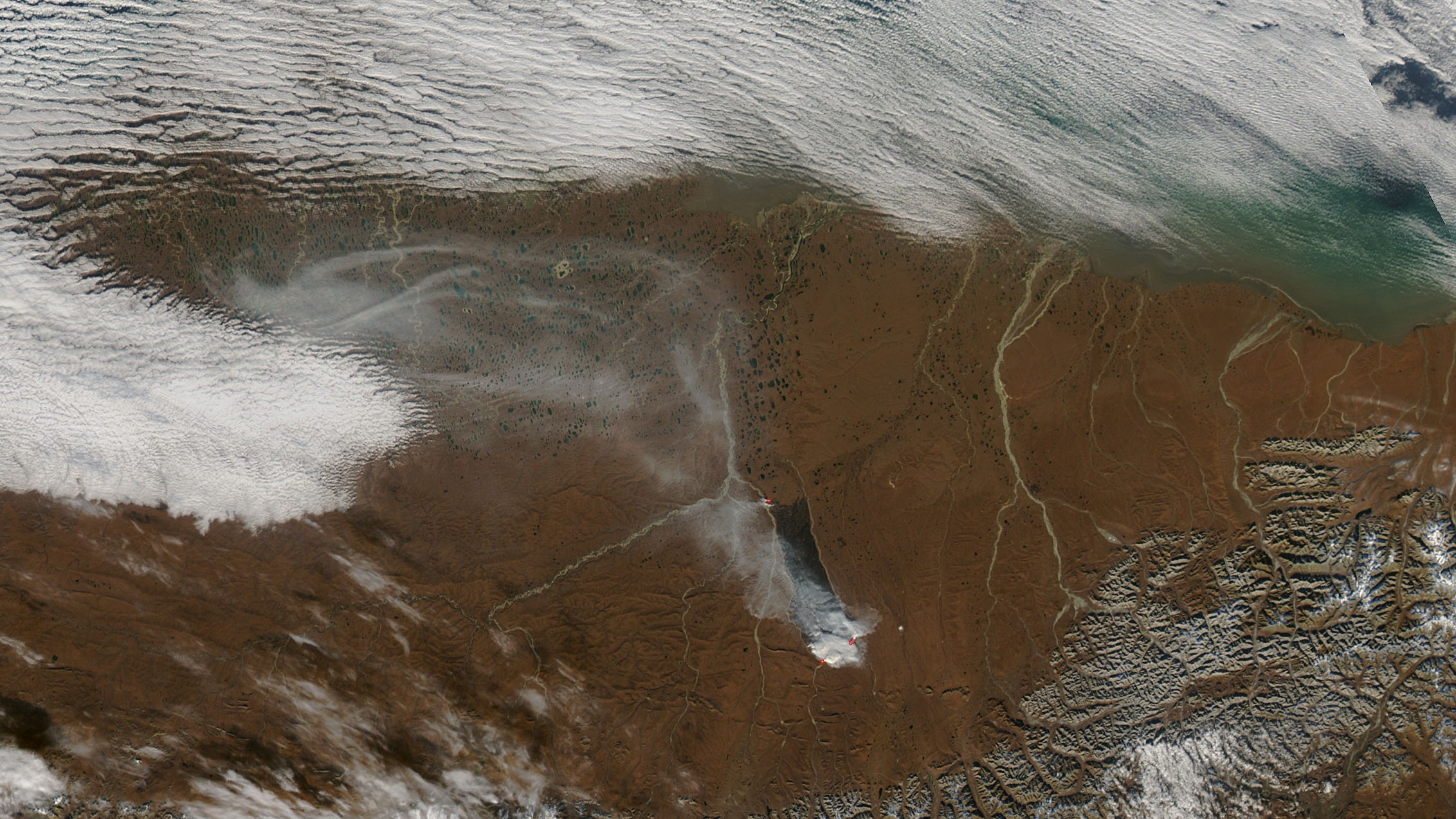

Bertrand Loyer almost drowned while filming an underwater volcano near Tonga, in the South Pacific. But even drifting for a night during a storm couldn't deter Loyer and his crew from capturing erupting volcanoes around the world for a new PBS documentary, "Life on Fire."

From a surprise encounter between sooty seabirds and deep-sea shrimp, to Alaska's famous salmon runs, four episodes in the six-part series explore the relationship between wildlife and volcanoes. Then "Volcano Doctors" presents the latest in eruption-prediction science. An aerial tour of the aftermath of the Eyjafjallajökull eruption, which premiered Wednesday (Jan. 2) on PBS, examines which Icelandic volcano may erupt next. The series airs on PBS through Feb. 6.

OurAmazingPlanet spoke with Loyer to learn more about the physical and technical challenges of filming active volcanoes.

OurAmazingPlanet: What was the most difficult technical challenge in filming?

Bertrand Loyer: There have been several of them. One was to make sure we would bring the expensive Cineflex technology [a stabilized, high-definition camera] at a good time.

Volcanoes and eruptions generally work on their own agenda, and we're spending approximately $30,000 on an aerial cutaway of an eruption. We would study the past eruptions, to know what kind of cycle the volcano is on. We also take a lot of precautions, on the eruption but also on the weather. We need to juggle all those parameters, but at the end of the day, it pays off. It can definitely give you angles which are very, very hard to get otherwise.

I won some bets with some friends to anticipate the eruption dates.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

OAP: How long did it take to film the series?

B.L.: I started back in 2001, with the very first episode. We were waiting for a bloody volcano to create an island. It took a while for our little planet to send us that show. But by the time it happened, a storm came, so I had no chance. I called the European broadcaster [the sponsor], and said we were having a bit of a problem: we were in the middle of the South Pacific, with no volcano to film. But there was another one erupting nearby, so would they be interested if I just created from scratch a new episode? So I took the risk, brought our expensive equipment, plus another expensive gizmo, the Cineflex, and we did get an eruption and came out with very spectacular footage.

There is a lot of random aspect in it, of course. We are depending on the activity of the volcano. But volcanoes, when you want to tell a story, you have a before, during and after of an eruption. You have a three-part narrative arc of a story, and this is great, because the volcano is bringing a lot of drama to the story.

OAP: How did you become interested in geology and volcanoes?

B.L.: I wondered, "What are the forces guiding and shaping our planet?" And my training is a bit of engineering and biology, so a mixture of the two gave birth to the series.

When you spend your time on the slopes of a volcano, you want to just know more. It's a virus. It's a virus you're catching.

OAP: What is one important thing people don't know about volcanoes?

B.L.: I would say, expect the unexpected, because we tend to describe volcanoes by saying it is just a mountain of fire. But we figured out you can't really categorize a volcano. One unique volcano can change its mood from day to day.

OAP: What did you learn in filming the series?

B.L.: We've learned a lot, actually. Because we have access to things that are very short in time, very ephemeral, we've learned about the extraordinary changes at the surface of the volcano itself. Also things about the wildlife, which are not really expected, like the deep-sea shrimps and the way they are being eaten by the tern [seabirds]. [The mystery of how the terns catch the shrimp is revealed in "Pioneers of the Deep," which airs Feb. 6.]

We did learn it's not necessary to be there on day one of the eruption. In fact, we had some cases where on day three, four or five, the eruption was at full power [instead of on day one].

OAP: Since our site is called OurAmazingPlanet, what's your favorite amazing thing about the planet?

B.L.: It's a combination of what's on the volcano, its energy from the depths and what happens when that energy is being released. It is the elements, and especially the clouds. The clouds formed [when volcanoes erupt] are quite a display of energy. You get a lot of lightning, purple lightning, entire clouds being cross-crossed by lighting. Those kinds of things are probably the most spectacular display that comes to mind in this series. It makes you feel like you're dust in the wind.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus