What Does the Fiscal Deal Mean for Science?

The deal that lawmakers and the White House finalized late Tuesday (Jan. 1) to avert going over the fiscal cliff leaves science agencies in limbo, delaying a decision on budget cuts for two more months.

The agreement does, however, reduce the potential impact of these cuts.

"I am hopeful they will find a deal that spares the worst of these cuts, that takes a much more balanced approach," said Matt Hourihan of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Tuesday's tax deal, he said, "is a step in that direction."

The mandatory cuts would affect the current year's budget as well as future ones, leaving agencies such as the National Institutes of Health, NASA and the National Science Foundation in limbo.

"This deal doesn't change that at all, it just extends that condition of uncertainty into the next couple of months," said Hourihan, director of the AAAS research and development budget and policy program.

Had no deal been reached as the New Year began, Hourihan estimates that mandatory across-the-board cuts to research and development, both in defense and elsewhere, would have come to about 9 percent.

Negotiators managed to knock off about one-fifth of that cut for this year, then kicked the can down the road by delaying the deadline until March 1. [7 Great Dramas in Congressional History]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These budget cuts, mandated by the Budget Control Act of 2011 and known as sequestration, were an important element of what is known as the fiscal cliff. Politicians struggled to address the fiscal cliff, which also involved the expiration of tax cuts.

The highest-profile element of Tuesday's deal —income tax increases on those making $400,000 per year or couples making $450,000 or more — was separate from sequestration. It does not affect the prospect of mandatory spending cuts.

For this fiscal year, the mandatory cuts would have reduced federal spending by $109 billion. But the deal made changes to rules regarding retirement accounts, with the intent of raising $12 billion. It also trades one type of cut for another. Congress has agreed to make $12 billion in cuts, divided between this year and next.

Under sequestration, the Office of Management and Budget must allocate the cuts as mandated by the law. However, the $12 billion in cuts made as part of the deal are different. This time, Congress will have the power to pick and choose the areas that lose funding, Hourihan said.

This means science agencies may or may not be affected by the $12 billion in cuts.

The deal reduces the potential cuts to this year's budget to $85 billion, but potential cuts for future years remain unaffected, according to an analysis by the AAAS.

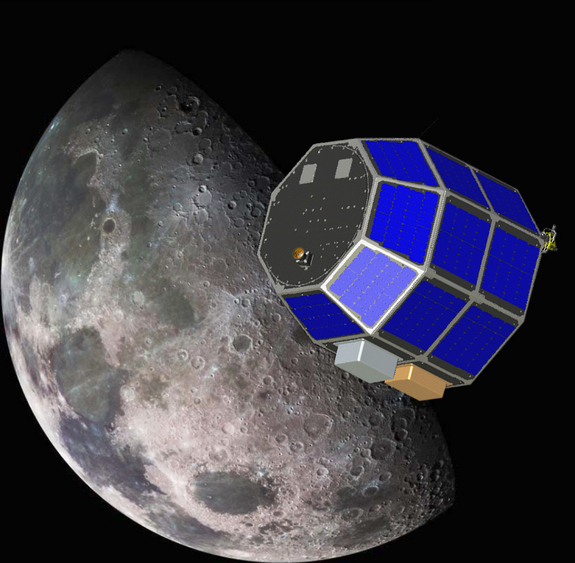

Budget cuts for science agencies mean less money to spend on equipment, facilities or research. For NASA, for example, this could mean cutbacks in missions, Hourihan said.

For the NIH or the NSF, both of which provide funding to the academic community, cuts could mean fewer and smaller grants, and, as a result, less support for graduate students and others becoming established as scientists, he said.

Prior to the deal, NIH director Francis Collins told a congressional subcommittee that sequestration would require the NIH to award 2,300 fewer grants.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.