Mayan Apocalypse Countdown: 1 Month 'Til Doom

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Are you ready for the end? Or perhaps a new beginning?

Either way, buckle up, because today marks the one-month countdown until the 2012 Mayan Apocalypse, set for Dec. 21. That date corresponds to the end of the 13th b'ak'tun, or 144,000-day cycle, on the Maya Long Count calendar, marking a full cycle of creation, according to the ancient Maya.

This milestone has triggered both fear and excitement in some subcultures, particularly online. Some believers see the day as a true doomsday, when the Earth will be destroyed in a planetary collision or other major disaster. Others see it as a day marking a new dawn of peace and unity.

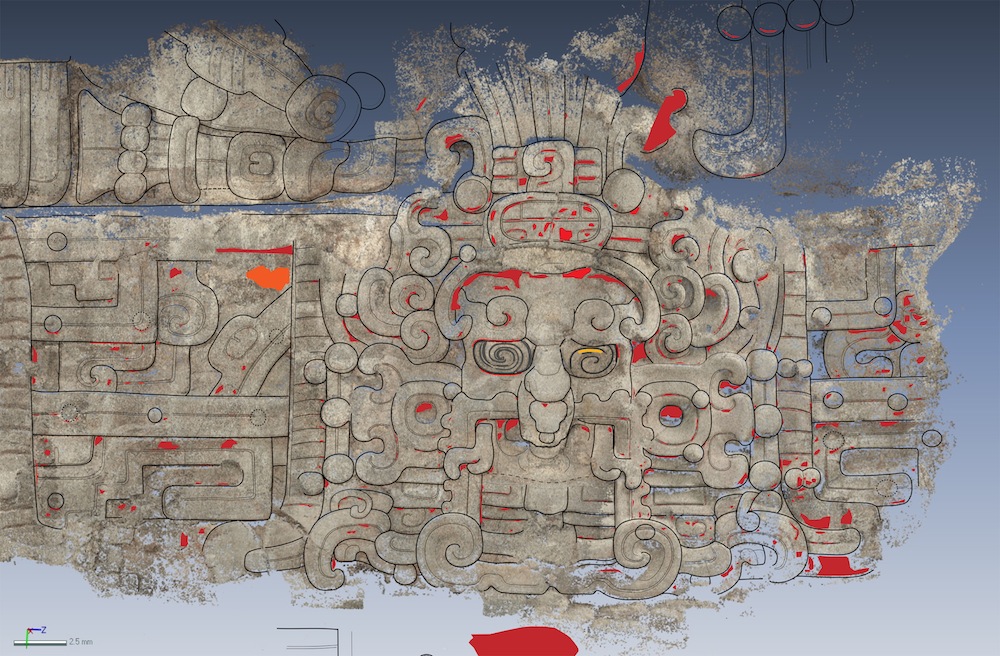

All of this excitement stems from two ancient texts found in Central America and dating back to the heydays of the Mayan Empire. One calendar inscription was found on a monument made around A.D. 669 in Tortuguero, Mexico, and refers to the coming of a god associated with cycle changes on the Dec. 21 date. (Of course, since December is an invention of western calendars, they didn't use quite those terms.) [Doom & Gloom: Top 10 Post-Apocalyptic Worlds]

A second inscription, unearthed this year in Guatemala, refers to a struggling king who called himself the "13 k'atun lord," an effort to tie himself to the 13th b'ak'tun of Dec. 21, 2012. This was likely a public relations move designed to shore up support after the king suffered a crippling defeat in battle a few years before.

In neither text were apocalyptic predictions made. But when westerners caught wind of the Mayan calendar, they mixed in their own end-of-the-world mythology, much of it stemming from Christianity, and created a new legend, according to University of Kansas Maya scholar John Hoopes.

Apocalypse predictions are a fairly frequent occurrence in western civilization. Most recently, radio preacher Harold Camping gained notoriety after predicting Judgment Day on May 21, 2011 and the end of the world on Oct. 21 of that year. Camping had initially claimed the world would end in 1994, later asserting he had gotten his Biblical math wrong; the real date, he said, would be Oct. 21, 2011.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The real Mayan Empire did actually end, of course, albeit slowly and not on anyone's predicted timetable. Environmental evidence suggests that drought helped crumble advanced Mayan cities and may have kept them from rebuilding once their political institutions collapsed.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappasor LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook& Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus