The Mystery of the Money Tree Revealed

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Buried in ancient Chinese tombs, money trees are bronze sculptures believed to provide eternal prosperity in the afterlife.

One money tree was crafted in southwest China during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 CE). Supported by a ceramic base, this rare piece of art stands 52 inches tall and spans 22 inches wide. Dragons and phoenixes — symbols of longevity — and coins decorate the tree's 16 bronze leaves.

The Portland Art Museum acquired the tree as a gift from a private collection. There was little information available about the tree and no documentation as to the time or place of its excavation. It was also unclear whether the tree had all of its original parts from the Han Dynasty or if replacement parts had been added. Nor were the artistic details fully visible, due to layers of corrosion.

The museum partnered with assistant professor of chemistry Tami Lasseter Clare and her team from Portland State University to learn more about the tree and its mysterious past.

Clare had several goals: identify points of breakage in the tree and determine how to prevent breakage in the future; identify the tree's material composition to see if it dated to the Han Dynasty; identify the corrosion products and layers of materials that accumulated over time and, determine if all parts of the tree were original.

The benefits of this research are largely educational, Clare said. "Many major museums employ scientists who study similar issues; however, no museums in the Pacific Northwest do. This project was a rare opportunity to collaborate with the Portland Art Museum and to demonstrate what 'secrets' can be learned using scientific methods." Clare also explained that some of the research findings are featured in an exhibition at the Portland Art Museum, "which is an exciting outcome for this work."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

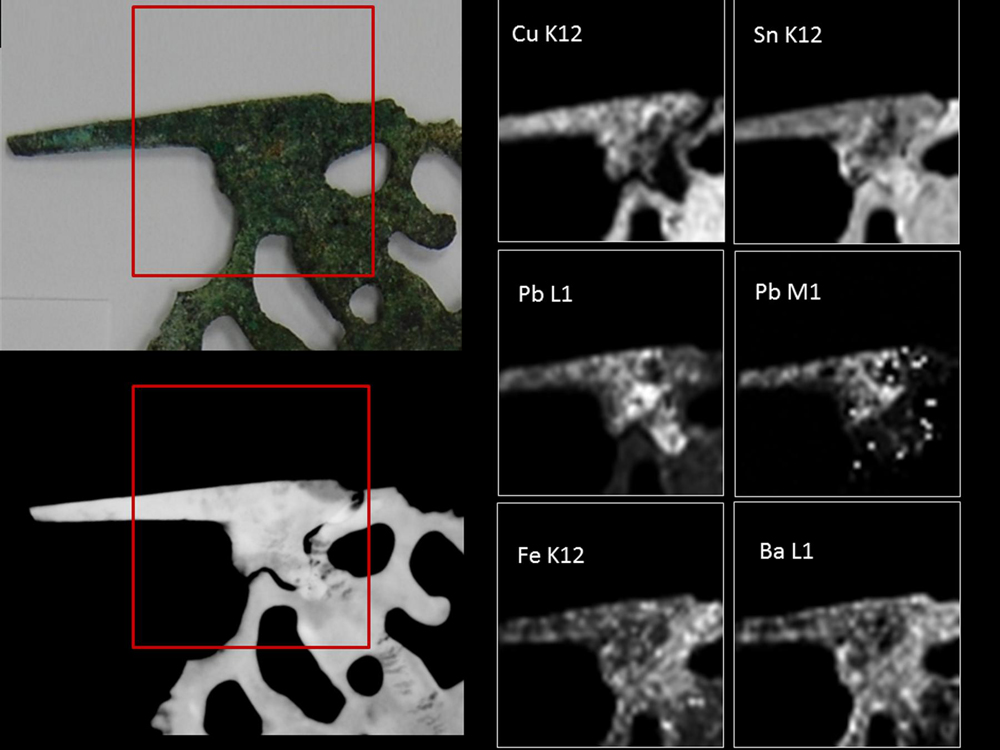

Clare and her team used various techniques to "look beneath the surface" of the tree and determine the chemical composition. They used X-radiography, which is an imaging technique that uses X-rays to study an object or materials' structure and composition. The X-rays pass through different parts of the sample object or material and an image is recorded based on how the varying parts of the sample absorb radiation. The images are displayed in different tones depending on the intensity of the X-ray. This process is especially useful for examining metal objects, such as the tree, covered by corrosion, as well as paintings with multiple layers of paint, biological samples and other objects and materials with multiple layers.

Using this technique, the team identified weaknesses and cracks in the tree and areas that needed extra reinforcement and handling care. This information also helped determine areas of the tree that might be prone to future breakage.

In addition, the team used X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and fourier transform infrared micro-spectroscopy to identify the tree's chemical composition and the encrustations, or what Clare explains are "the layers of material that adhered to its branches as a result of its presumed burial, often composed of sand, calcite and corrosion products." XRF is specifically used to find the elemental composition of solid materials using an X-ray beam, and FTIR is used to determine various types of infrared spectrums that can identify and study chemicals.

These techniques helped the team learn valuable information about the money tree and its history. They determined it was made using cast bronze, each piece of the tree produced via molten bronze set in a two-part mold.

They also learned that the tree was buried in the ground at some point. Clare observed "thin, almost hair-like roots" that grew within or on top of the encrustation layers of the tree. Some of the roots were covered in a crust of calcite, or calcium carbonate. Further evidence that the tree was buried included some of the corrosion products on the tree — azurite (a copper mineral) and malachite (a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral) — which are common minerals found on bronze objects buried in the ground.

Although encrustations and corrosion products helped prove that the tree spent time underground, they were covering artistic details of the tree. Using X-radiography, the team learned that encrustations covered the entire figures of two monkeys holding bananas, and also the outlines of dragon gills and eyes that form the "foliage" on the branches.

Encrustations were not the only additions that transformed the tree over time.

The team determined that the tree was repaired numerous times in the past with replacement parts that did not match the originals. The replacement parts were made with a different method, had a different chemical composition and lacked the design detail of the original.

"The numerous and distinct repair methods suggest that the [tree] may have changed hands several times, though the record of ownership is not known," said Clare.

Instead of bronze casting, the repairers manufactured replacement parts using mechanical cutting tools and abrasives. They attached the pieces to the original tree using lead-tin solder, a fusible metal alloy. Via X-ray fluorescence and infrared spectroscopy, the team also learned that the chemical composition of the replacement parts was different than the composition of the original. These tenons — pieces that fit into notches and attach branches to the trunk or one another — were more likely to break because they carried the weight of the branches.

While those who repaired the tree attempted to make the replacement parts blend in with the original, their efforts were ultimately in vain.

"Interestingly, the replaced parts had been painted to match the blues and greens of corroded bronze and the white color of the encrustation layers, showing that whoever made the replacements didn't want those pieces to be visibly different from the others, probably to increase the market value of the tree," said Clare.

Currently the money tree is at the Portland Art Museum as part of an exhibition, "Cornerstones of a Great Civilization," which features Chinese art masterpieces. The exhibition will run through Nov. 12, 2012.

Editor's Note: The researchers depicted in Behind the Scenes articles have been supported by the National Science Foundation, the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Behind the Scenes Archive.