How Sputnik Changed the World 55 Years Ago Today

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

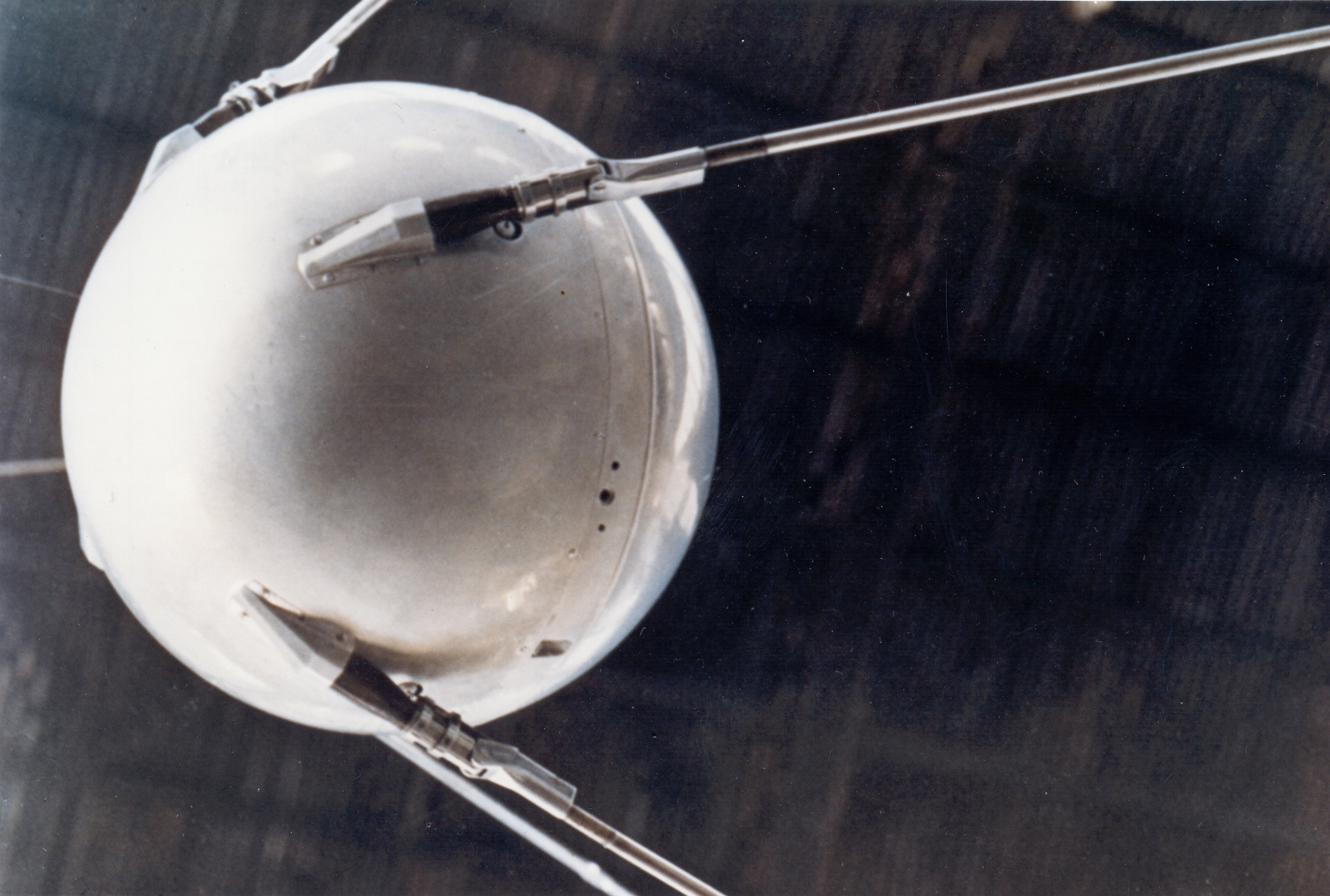

Fifty-five years ago today, the Space Race was kicked into gear by a silver basketball flying through the sky.

Sputnik 1, the Soviet probe that became the first manmade object to reach space, launched Oct. 4, 1957. The feat proved the Soviet Union's technological bonafidesand spurred the United States into stepping up its game in space.

The anniversary is being marked by the 13th annual World Space Week, which includes hundreds of space-themed events in dozens of countries from Oct. 4 through Oct. 10.

Traveling companion

Sputnik ("traveling companion" in Russian) was a small sphere about 22 inches (56 centimeters) in diameter, with four long antennas protruding from its head. The 183-pound (83 kilograms) probe used a radio beacon to send a beeping sound back to Earth as it orbited the planet every 98 minutes.

This beeping was played over the world's radio stations, and in combination with the sight of the probe orbiting Earth, sparked fear in Americans that our country was falling behind the Soviets in technological capability. [Graphic: How Sputnik Worked]

At the time, Sputnik's significance lay in the prestige it gave the Soviet Union and the anxiety it provoked in that nation's Cold War enemies. Fifty-five years later, however, historians say this first artificial satellite's biggest impact was the incredible legacy of space exploration achievements it inspired.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In the 55 years since Sputnik first beeped its way around the planet, the small silver sphere with its whip-like antennas has transcended the Soviet Union's success to become a symbol for a global Space Age," said space history and artifacts expert Robert Pearlman, editor of collectSPACE.com.

Sputnik has been credited for helping instigate President John F. Kennedy's 1961 declaration that America would put a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s — a move designed in part to reestablish U.S. technological superiority.

Without Sputnik, as well as the Soviet Union's ensuing achievement of putting the first man into space — Yuri Gagarin in April 1961 — experts have questioned whether American astronauts would have walked on the moon as soon as they did, or ever. In a sense, the victory of the Apollo 11 moon walk in July 1969 can be traced all the way back to Sputnik.

New beginning

This heritage is seen not just in the fame the tiny satellite holds on to, but in the enduring popularity of Sputnik collectibles, Pearlman said.

"Gracing stamps, models, toys, medallions and jewelry, Sputnik's shape and sounds continue to embed themselves in our pop culture," Pearlman told SPACE.com."The real Sputnik may have fallen out of orbit in January 1958, but its impact and iconography continue to circle the world today."

At this point, more than half a century after the probe's launch, the United States is facing another key moment in space. The 30-year space shuttle program is finished, and NASA is regrouping for its next phase of space exploration.

President Barack Obama has challenged the space agency to send people to an asteroid by 2025, and to Mars by the mid 2030s. NASA is outsourcing transportation of its astronauts to the International Space Station to the private sector, and aiming to build a new heavy-lift rocket to travel beyond low-Earth orbit.

In economically troubled times, space advocates are having a hard time convincing lawmakers and taxpayers that space is worth the expense. Perhaps we need another Sputnik moment to fire up the nation about space the way that little satellite did 55 years ago.

To find World Space Week events near you, visit the official site here: http://www.worldspaceweek.org/.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus