Why America's Love Affair with Cars Is No Accident

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Drivers may feel spooked by seeing the first self-driving cars appear in coming years. But the new era could prove far less disruptive and bloody than the automobile's 20th-century battle to push pedestrians off U.S. streets.

The change in American public opinion from thinking of cars as wildly dangerous vehicles to having a "love affair with the automobile" was no accident. Instead, it reflected a serious push by the car industry to change people's psychology. Automobiles had to win the battle for hearts and minds before they could take over streets where people had once swarmed.

"That's not the natural order of things; that's the result of a real struggle," said Peter Norton, a historian of technology at the University of Virginia. "That struggle may have analogies with what we're facing in the future with autonomous vehicles."

One key difference between the two eras of transition may prove to be a huge blessing — the rise of self-driving cars could boost road safety and eliminate thousands of unnecessary motorist deaths in the U.S. each year. That futuristic scenario stands in contrast to the relatively bloody rise of cars in the early 20th century.

A bloody beginning

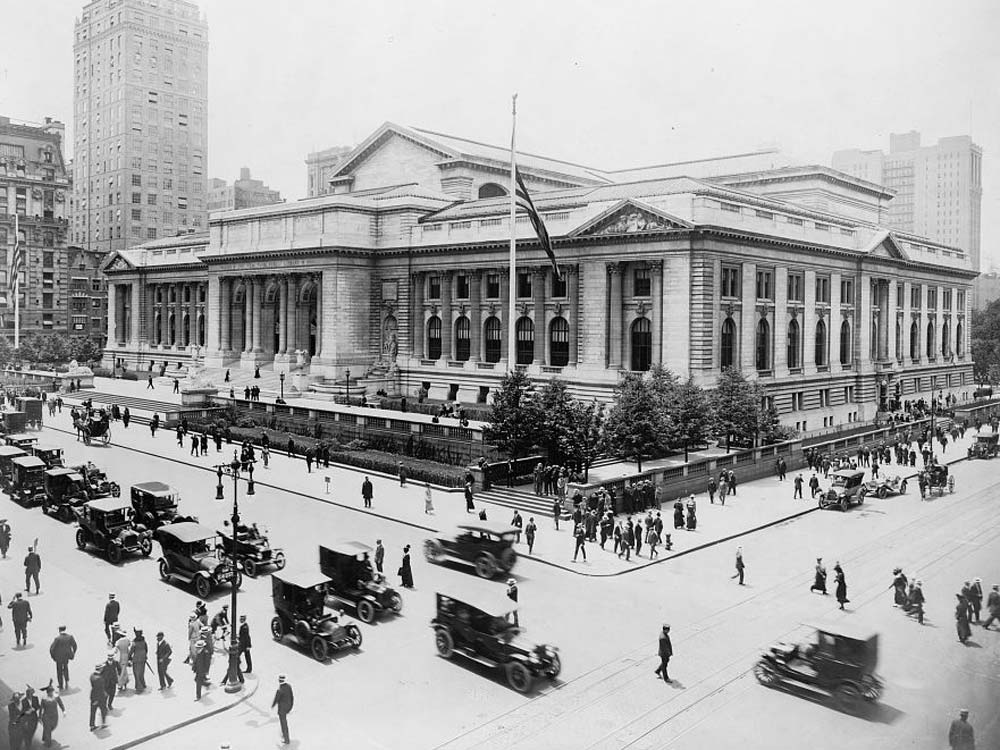

American hearts and minds did not change easily when cars first appeared. Pedestrians crowded the streets of U.S. cities and towns at the start of the 20th century, walking alongside horse-drawn wagons, carriages and trolleys. Contrary to modern sensibilities, parents thought it was perfectly normal for their kids to play in the streets.

"If a pedestrian strode into a street and maybe a wagon wheel ran over their foot, the law would be on their side," Norton told InnovationNewsDaily. "Judges would say pedestrians belonged there, and that if you're operating a heavy dangerous vehicle, it's your fault."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Car accidents led to injuries and deaths among pedestrians and a strong public backlash against automobiles, Norton said. He found newspapers of the time commonly ran cartoons showing the grim reaper at the wheel of a car running over children — part of his research for the book "Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City" (MIT Press, 2008).

People even pushed for a 1923 law requiring all cars in Cincinnati to have a mechanism limiting their speed to no higher than 25 mph, but car makers gathered enough support to defeat it.

America's affair with the automobile

The automobile industry eventually began waging a psychological campaign to get pedestrians out of the streets. First, it invented the term "jaywalking" (a reference to the idea of jaybirds as loud idiots) to make fun of pedestrians walking in the street as being stuck in the past.

Second, schools helped train new generations of children to avoid the streets when the American Automobile Association (AAA) became the top supplier of safety curriculum for U.S. schools in the 1920s, Norton explained. The AAA also spread the idea of school safety patrols to help keep kids out of the street.

The popular phrase "America's love affair with the automobile" eventually came along in a TV show called "Merrily We Roll Along" as part of the DuPont Series of the Week in 1961 — a time when DuPont owned a large percent of stock in General Motors. American comedian and actor "Groucho" Marx used the phrase in his narration of the show until it stuck in people's minds.

Usage of the phrase was nonexistent in newspapers "until 1961, when it goes straight up and never goes down again," Norton said. "It was introduced by the show and seen by millions of people, who eventually forget it was invented."

Nobody at the wheel

The first commercial self-driving cars may inherit a world already built for automobiles, but they still need to know how to share the road with drivers, bikers and pedestrians, said Peter Stone, director of the Learning Agents Research Group at the University of Texas in Austin. His group has tested its own driverless car alongside simulations to see how intersections could work with self-driving cars.

"I personally bike to work often, so I'm definitely not interested in creating a system where it's not feasible to have bikes on the road," Stone said. "You'll still have traffic signals, so it's not too difficult technically for bikes to approach intersections and have periods of safe passage."

Safer streets seem like a win for everyone. But Norton cautioned that self-driving cars may also blind people to public transportation or walking solutions for towns and cities — especially in a world filled with rising fossil fuel costs, carbon emissions contributing to climate change and urban sprawl.

"We inherited the mental model of getting everywhere in a car alone, and we've adopted so fully that we're envisioning the future like that," Norton said. "But the history of automobiles shows us mental models can change. If we can change the mental model, why not change the future?"

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to Live Science. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus