Live Science's top stories of 2020: Writers' choice

From a mirror universe to X-shaped galaxies, these stories guaranteed that 2020 would be a year to remember.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

At Live Science we cover hundreds of science news stories each month, totalling more than one thousand over the course of a year. That's a lot of science! So as 2020 winds down, we're taking a look back, revisiting and spotlighting many of the year's top stories — as we usually do. But during this exceptional year, we'd also like to showcase a few of the articles that stood out to our reporters and editors.

For the first time at Live Science, we've asked our writers and editors to pick the stories that made the biggest impressions on them in 2020. From a mirror universe to X-shaped galaxies, these stories guaranteed that 2020 would be a year to remember.

A mirror universe?

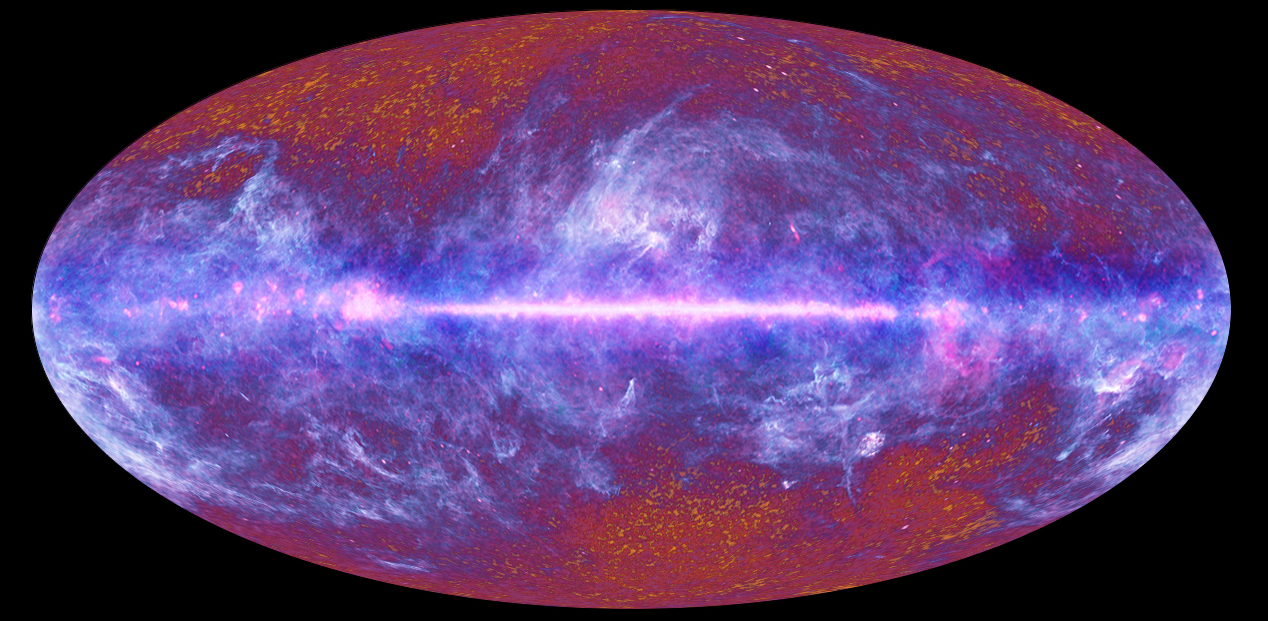

Rafael Letzter, Senior Writer: My favorite science story this year wasn't true at all. Over the summer, a bunch of tabloids misread a 2018 paper about a fascinating subject — the mysterious particles detected shooting out of the ground in Antarctica, and how they relate to an unusual theory of time — and claimed they were coming from a "mirror universe." But their error was our gain: It gave us an opportunity to learn about this bizarre theory of time, and a real mirror universe that might be hiding in space-time behind the Big Bang. This one's got all the hits: dark matter, unsolvable equations, a "fourth type of neutrino" and the cosmic microwave background.

Read more: Why some physicists really think there's a 'mirror universe' hiding in space-time

Solar disruption

Kimberly Hickok, Reference Editor: My favorite science story this year was about how solar storms could be messing with the ability of gray whales to navigate Earth's oceans.

Research presented at the 2020 Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology conference found that healthy gray whales are nearly 4.5 times more likely to strand when our sun has lots of sunspots, which indicate increased solar storm activity and high emissions of radio waves.

Scientists have long suspected that gray whales use Earth's magnetic field to navigate. So, it's possible that when something disrupts Earth's magnetic field, such as a solar storm, it causes the whales to make a navigational error and strand.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But scientists don't know for sure if whales even have a magnetoreceptive sense or not, so maybe something else is going on. All that's clear right now is that healthy gray whales strand more often when the sun is acting crazy.

Read more: Solar storms might be causing gray whales to get lost

Understanding "long COVID"

Nicoletta Lanese, Staff Writer: I've been covering COVID-19 since January, writing articles about the virus's biology, the thorny logistics of vaccine development and contact tracing, the threat evictions pose to public health, and everything in-between. Of all the stories I've written, this one stands out most in my memory, not as a happy story, per se, but as a hopeful one.

This story features several "long-haulers" — people who contracted COVID-19 and remained ill for many months after their initial infections subsided. When doctors couldn't offer them answers, long-haulers formed online communities to validate each other's experiences and offer emotional support. But what began as a collection of internet forums blossomed into a full-blown movement to understand "long COVID."

This story highlights the early efforts of these patient-led research groups. Their advocacy continues today, but now, the broader scientific and medical community has joined the charge.

Read more: 'We just had no answers': COVID-19 'long-haulers' still learning why they're sick

COVID-19 origins

Jeanna Bryner, Editor-in-Chief: One of the most intriguing questions yet to be answered about the novel coronavirus causing COVID-19 is: Where did it originate? Back in the spring, I explored that question in a couple of articles that left more questions than answers, and the experts contacted by Live Science indicated there's a chance we'll never know exactly where the virus came from. Even so, scientists know the virus most closely matches coronaviruses found in certain populations of horseshoe bats that live in Yunnan province, China. However, even if they know the virus likely originated in a horseshoe bat, scientists aren't sure how it hopped to humans and whether an intermediary host was involved — several intermediaries have been proposed, including pangolins and even snakes. Though some conspiracy theories took off earlier in the pandemic suggesting the virus was human made, several genetic analyses suggest that is very, very unlikely. And the idea that the virus somehow "escaped" from a virology lab in Wuhan that works with coronaviruses also seems unlikely. Live Science will keep you up to date as we learn more about the origins of SARS-CoV-2.

Read more: Wuhan lab says there's no way coronavirus originated there. Here's the science.

X marks the spot

Brandon Specktor, Senior Writer: My favorite story of 2020 was about the strange, boomerang-shaped galaxy PKS 2014−55. When seen with radio telescopes, this galaxy looks like a giant X in the sky, each arm stretching into space for tens of millions of light-years (or about 100 times the length of the Milky Way!). The question is: why?

I spoke to Bill Cotton of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Virginia about it. He and his colleagues had just mapped this crazy galaxy with South Africa's massive MeerKAT radio telescope, and developed a truly incredible image of it. The image clearly shows two jets of super-charged matter flying out of the galaxy's central black hole, then being repelled backwards by the pressure of intergalactic space. Some of that retreating matter bounced off of the galaxy's dusty disk, creating the vivid boomerang shape we see here.

I looked at hundreds of astronomy photos this year, and this one is my favorite. Bill was also the first person I interviewed over Zoom during the spring lockdown. Seeing him at home with a big calendar of X-shaped galaxies behind him gave me a strange sense of hope that there was still more to life than COVID.

Read more: The sky is full of weird X-shaped galaxies. Here's why.

Hard to swallow

Rachael Rettner, Senior Writer: My most memorable story of 2020 was on an unusual case of a teenager who unknowingly swallowed a sewing pin that pierced his heart. As a health reporter, I've seen my fair share of strange medical cases, but this one stood out. I had never heard of a sewing pin, or other ingested foreign object for that matter, traveling through the stomach and into the heart, as doctors believe happened in this case. Fortunately, doctors were able to remove the sewing pin via open heart surgery, and the teen experienced no complications.

Read more: A teen unknowingly swallowed a sewing pin. It pierced his heart.

Ice age miners

Laura Geggel, Editor: During the last ice age, humans in what is now Mexico ventured into pitch black caves, risking life and limb to mine a valuable mineral. It wasn't gold or silver they sought, but ochre — a crayon-like reddish pigment used for rituals and everyday activities.

This finding, published in the journal Science Advances, shows just how clever and driven humans were 12,000 years ago. We tend to think of prehistoric humans as people who weren't terribly sophisticated, but that's far from the truth. In this case, the Indigenous people of the Yucatan Peninsula carried torches into the caves, made stone tools and crafted stone markers al la Hansel and Gretel so they wouldn't get lost. They did all of this work to mine ochre, which they possibly used as a sunscreen or bug repellent. Talk about relatable! I stock up on similar supplies every summer.

Read more: Ice age mining camp found 'frozen in time' in underwater Mexican cave

Eerie image

Tia Ghose, Assistant Managing Editor: My favorite story of the year, about the longest-exposure photo ever taken, came about thanks to a few key elements: time, luck and beer!

When UK-based graduate student Regina Valkenborgh poked a hole in a beer can and taped some photo paper to it eight years ago, she had no idea she would be breaking records. The photographer had created a low-tech “pinhole camera,” suitable for tracking slow-moving objects over time, and affixed it to a telescope at the Bayfordbury Observatory at the University of Hertfordshire. Then, she promptly forgot about it.

Luckily for Valkenborgh, a staff member at the observatory recently detached the beer can and discovered the treasure attached to it.

The end result? An eerie blue image of the sun’s neverending dance across our sky. The time-lapse photo, which captures 2,953 arcs of light from the sun, beats the next-best record holder for longest-exposure image by four years.

Read more: Longest-exposure photo ever was just discovered. It was made through a beer can.

mRNA vaccines

Yasemin Saplakoglu, Staff Writer: My favorite story this year was about mRNA vaccines and how they could dramatically reshape vaccine production in the future. Two of the leading COVID-19 vaccines are based on mRNA, a strand of genetic code that primes the immune system to fight the novel coronavirus. The day we published this feature article, the Food and Drug Administration approved the very first coronavirus vaccine — based on mRNA — for emergency use in the U.S. A few days later, healthcare workers received the very first doses across the country. Having followed and reported on the development of COVID-19 vaccines since the very first clinical trials, it was heart-warming to be able to write a hopeful story. COVID-19 vaccines, which were rolled out on unprecedented timescales, are truly one of the most impressive scientific achievements of 2020 — and writing about them has left me in awe.

Read more: COVID-19 vaccines: The new technology that made them possible

Backdoor exit

Mindy Weisberger, Senior Writer: Biologists are constantly finding new examples of animal weirdness, and this story was one of the more unusual cases that I read about this year ... or any year, really. It's about a water beetle that performs an ingenious escape from a frog predator after the frog swallows it.

And the beetle exits the frog through a different route than the one it came in by.

When pond frogs gulp down the aquatic beetle Regimbartia attenuata, the satisfaction from their meal is short-lived. The slippery beetles emerge unscathed just a few hours later, squeezing out of the frog's anal opening, or vent. A frog's vent is typically held tightly shut by sphincter muscles, but researchers suspect that the swallowed beetle may be stimulating the frog's defecation reflex to open a portal to safety.

After witnessing a beetle's escape, scientist Shinji Sugiura of Kobe University in Japan was "very surprised," he told me. I expect that the frog was pretty surprised, too.

Read more: After being swallowed alive, water beetle stages 'backdoor' escape from frog's gut

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus