Yellowstone Supervolcano May Have Had More Eruptions Than Thought

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The supervolcano that lies beneath Yellowstone National Park might have erupted less powerfully but more frequently than previously thought, new research suggests.

In the ancient past, the supervolcano at Yellowstone led to some of the largest-known continental eruptions in Earth's history. Each of the world's roughly one dozen supervolcanoes is capable of spewing up to thousands of times more magma and ash than any eruption ever recorded in human history.

Scientists now find that the biggest Yellowstone eruption — the fourth-largest known to science, which created the 2-million-year-old Huckleberry Ridge deposit — was actually at least two different eruptions that occurred about 6,000 years apart.

Sharper focus

To see when the eruptions took place, the researchers analyzed rocks from Yellowstone to look at isotopes of particular elements (isotopes have different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei). The rate at which the isotope potassium-40 radioactively decays to become the isotope argon-40 is known, and by analyzing the ratio of argon and potassium isotopes within these rocks, researchers could determine when they were laid down by eruptions. [Infographic: The Geology of Yellowstone]

Researcher Darren Mark at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Center recently helped improve this dating technique by 1.2 percent — a small-sounding difference that can become huge across geologic time.

"It's like getting a sharper lens on a camera — it allows us to see the world more clearly," Mark said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

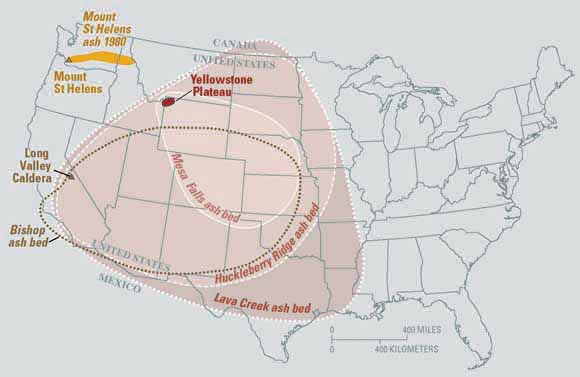

The new ages for each Huckleberry Ridge eruption reduce the volume of the first event to about 530 cubic miles (2,200 cubic kilometers), roughly 12 percent less than previously thought. A second eruption of about 70 cubic miles (290 cubic km) took place more than 6,000 years later. In comparison, the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens produced just about a quarter of a cubic mile (1 cubic km) of ash.

The first Huckleberry Ridge eruption still deserves to be called "super." By itself, it is the fourth-largest known to have occurred on Earth, darkening the skies with ash from southern California to the Mississippi River, said researcher Ben Ellis, a volcanologist at Washington State University.

"The big eruptions from Yellowstone are certainly still big," Ellis told OurAmazingPlanet.

More frequent eruptions

By knowing how this supervolcano behaved in the past, scientists can now better predict what it might do in the future.

"This research suggests explosive volcanism from Yellowstone is more frequent than previously thought," Ellis said.

These findings, detailed in the June issue of the journal Quaternary Geochronology, suggest that other supereruptions might actually be multiple, closely spaced eruptions as well.

"We can now show we have capability to split 'supereruptions' into smaller, more frequent events," Ellis said. "The ability to do this will impact upon the 'doomsday'-style scenarios which are commonly associated with supereruptions."

"It would be interesting to go to a series of big eruptions all around the world and really see what we can do with this technique," Ellis added.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus