Microbes Find Protection in Organized Communities

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This Research in Action article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Bacteria have very good organizational skills — so good that they actually get more orderly when they're put in small, crowded environments.

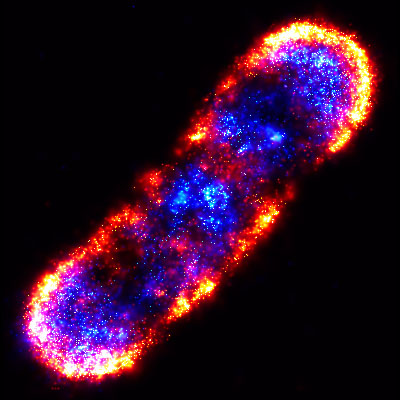

In this computer simulation, a few E. coli bacteria (blue rods) start out perpendicular to the walls of their square container. As the bacteria multiply and the space gets more crowded, they orient themselves into tidy columns (red rods) parallel to the container walls. The perfectly choreographed routine finishes with a flourish when the model bacterial community is pure red.

Bioengineer Jeff Hasty and physicist Lev Tsimring, both of the University of California, San Diego, put together this color-coded computer model to figure out how crowds of cells behave and communicate. The researchers wanted to know how a different density of cells in a given space affects organization. They found that the rod-like E. coli bacteria put themselves into a remarkably organized arrangement as the crowd expanded. In other words, this growing microbial metropolis progressed from disorder to a more ordered state.

Bacteria cluster into communities for the same reason humans do: it offers protection from hazards, in this case antibiotics. As Tsimring puts it, "when environmental conditions are harsh, bacteria like to stick together."

Learning the specifics of how bacterial cells organize themselves when they multiply is helping scientists better understand biofilms, dense sheet-like colonies of bacteria. Biofilms are the most common way bacteria organize themselves in nature. They're found on living tissues and on the surface of rocks, as well as on moist man-made objects like kitchen drains and hospital tubing.

Most biofilms are harmless to humans, but some are associated with tooth decay and infections of the lungs, ears and urinary tract. For these health problems and others, understanding how bacteria cluster and crowd could offer new insight into how to beat them.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

To see more cool images and videos of basic biomedical research in action, visit the Biomedical Beat Cool Image Gallery.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Research in Action archive

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus