NASA Rover Finds Rare Mars Rock With Clues of Ancient Water

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

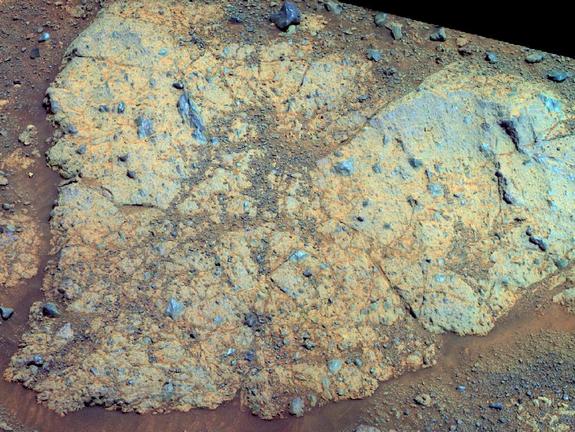

NASA's Opportunity rover has found an intriguing rock that could offer clues into Mars' wetter past.

Opportunity is more than seven years into its roving mission on Mars and arrived at the rim of the giant Endeavour crater in August. Just last week, the rover began studying a rock scientists have named "Chester Lake." The Mars rock appears to be much older than the geologic formations Opportunity has so far encountered.

"We've never seen a rock that looks remotely like this on Mars before," the rover's chief scientist Steve Squyres, a Cornell University geologist, said during a Planetary Foundation luncheon in Washington Sept. 9. [Photos: The Search for Water on Mars]

Opportunity and its twin rover Spirit landed on the Red Planet in January 2004. Both rovers far outlived their initial planned 180-day missions, but in May, NASA cut off communication with the ailing Spirit. Opportunity, however, is still going strong.

"Opportunity is just a really well-made vehicle," the rover's deputy principal investigator Ray Arvidson, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement. "It's way, way beyond warranty. It was supposed to drive about 600 meters and so far it's gone 33,500 meters in round numbers, and has taken maybe 150,000 pictures by now."

Opportunity's new location at the 14-mile (22-km) wide Endeavour crater offers the chance learn more about Mars' ancient times, when scientists think rivers of water flowed over the now dry surface. [Video: Opportunity Nears Endeavour Crater]

"The ancient rim of Endeavour represents a period when there was probably a lot more water on the surface," Arvidson said. "So, we're trying to get the chemical, mineralogical and geological setting to 'back out' those ancient conditions to reconstruct environmental conditions during this earlier time period."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While most Martian land has been covered over by more recent geological processes, the terrain at Endeavour crater's rim is thought to date back to Mars' earliest days, about 3.5 to 4 billion years ago. At this time, the Red Planet was being bombarded by space rocks that had not yet collected into larger bodies like planets and huge asteroids. Endeavour crater itself was likely created when one of these slammed into Mars.

The Chester Lake rock is a so-called breccia, meaning it contains many broken fragments of rock that have been cemented together, likely when Endeavour crater was formed.

Researchers plan to use Opportunity's Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) to clean off a layer of the Chester Lake rock's surface to expose deeper material. They hope this material will contain clay minerals that formed in the presence of water.

"Clays form in more neutral, less acidic conditions than the sulfate-rich sandstones we've been looking at," Arvidson said. "Our hypothesis is that if there are clay minerals, the water was less acidic and therefore more conducive to life."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus