Nubian Mummies Had 'Modern' Disease

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A "modern" disease of humans may have been what sickened ancient Nubian cultures, research on more than 200 mummies has found. The mummies were infected by a parasitic worm associated with irrigation ditches.

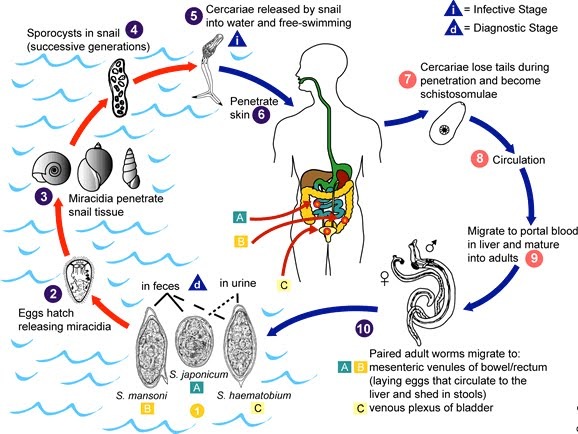

The disease, called schistosomiasis, is contracted through the skin when a person comes into contact with worm-infested waters. The disease infects over 200 million people worldwide a year; once contracted, the disease causes a rash, followed by fever, chills, cough and muscle aches. If infection goes untreated, it can damage the liver, intestines, lungs and bladder.

The species of Schistosoma worm, called S. mansoni, found to be prevalent in the Nubian mummies had been thought of as a more recent agent of disease, linked to urban life and stagnant water in irrigation ditches. [The 10 Most Diabolical & Disgusting Parasites]

"It is the one most prevalent in the delta region of Egypt now, and researchers have always assumed that it was a more recent pathogen, but now we show that goes back thousands of years," said study researcher George Armelagos of Emory University in Atlanta.

Although Armelagos and his colleagues weren't able to discern how bad the infections were in these Nubians, they said those who were infected would have felt run down — which would have affected their work (mostly farming).

Modern S. mansoni

Previous research showed that mummies from the Nile River region had been infected by Schistosoma worms, though new techniques are allowing researchers to determine which species.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team tested tissue from mummies from two Nubian populations (in the area now known as Sudan), dating from 1,200 and 1,500 years ago, respectively.

The earlier population, the Kulubnarti, lived at a time when their civilization's lifeblood, the Nile River, was at a high point, and there is little evidence of irrigation. They "probably weren't practicing irrigation; they were allowing the annual floods of the Nile to fertilize the soil," Armelagos told LiveScience.

The later population, the Wadi Halfa, lived a little farther south along the river and at a time when the water levels were lower; archaeological evidence indicates canal irrigation was in use to water crops.

The researchers expected each population would have shown signs of distinct species of Schistosomiasis; for example, S. mansoni thrives in stagnant water, while Schistosoma haematobium, another species that can infect humans, lives in flowing waters. (The team specifically looked for the antigens, proteins associated with the parasite, as well as the body's response molecules, antibodies.)

Irrigation issues

Here's what they found: About 25 percent of the 46 Wadi Halfa mummies tested were infected with S. mansoni, while only 9 percent of the Kulubnarti (191 individuals tested) were.

"In the past everyone has assumed S. haematobium was the source of the infection, and this study shows it was S. mansoni," Armelagos said.

The two populations also probably were infected with S. haematobium, said the researchers, who didn't test for its presence.

The irrigation canals built by the Wadi Halfa are the most likely source of the S. mansoni parasite, the researchers said. The Wadi Halfa probably contracted the disease when they used the canals to wash their clothes as well as flood the fields.

The study was published in the June issue of the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus