'Worm Therapy' Stimulates Gut Mucus

For some sufferers of inflammatory bowel diseases, relief comes in the form of a parasite cocktail: A deliberate infection with worms seems to soothe disease symptoms. Thanks to one man who volunteered his gut for science, a new study suggests the worms work their magic by stimulating mucus production and healing.

Ulcerative colitis, a type of inflammatory bowel disease, is marked by constant abdominal pain and frequent bloody diarrhea. The disease, which leaves the intestinal lining inflamed and ulcerated, isn't well understood. Some patients improve with immune-suppressing drugs, but these treatments can have major side effects. When all else fails, patients require surgery to remove part, or all, of the colon.

Frustrated by these options, some patients have turned to a treatment not for the squeamish-at-heart: Swallowing the eggs of parasitic worms. These worms, or helminthes, are able to modulate their host's immune system to stay alive. Several studies (along with anecdotal reports) have shown that as a side effect, inflammatory bowel symptoms decrease.

In the new study, published today (Dec. 1) in the journal Science Translational Medicine, researchers followed a man who deliberately infected himself with Trichuris trichiura, the human whipworm. It's an approach not recommended by doctors: The only worm that's been approved for clinical testing in the United States is Trichuris suis, a pig whipworm that survives in humans only temporarily. For this patient, however, the worms seemed to ease the ulcerative colitis symptoms, perhaps by stimulating immune cells to produce proteins that promote healing instead of inflammation.

Whipworm treatment

The patient, a 35-year-old man, was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis in 2003. In 2004, rather than take immune-suppressing steroids, the patient swallowed 500 whipworm eggs he had obtained from Thailand. Three months later, he downed an additional 1,000 eggs.

After taking the eggs ⎯ and seeing his symptoms improve to the point that he didn't need treatment ⎯ the man contacted P'ng Loke, now a professor of medical parasitology at New York University's Langone Medical Center. Then a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, Loke agreed to track the patient's progress and analyze just what was going on in the man's gut.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When he had colonoscopies for different reasons, we basically tried to characterize biopsies that were taken from his gut," Loke told LiveScience. "We tried to look at these biopsies and see what kinds of immune cells were activated… what kind of genes were activated. We were trying to put together a picture of what was going on in the gut at different times."

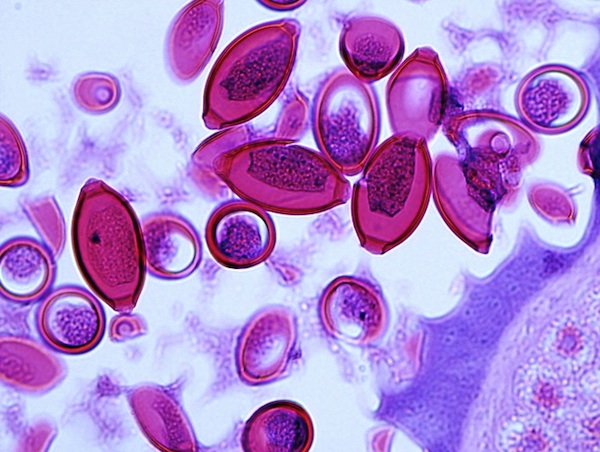

In 2005, Loke and his colleagues observed a symptom-free patient with a large intestine full of worms. In worm-infested areas, the intestinal lining looked healthy and mucus-rich. [Photo: Patient's worm-infected colon]

In 2008, the man's ulcerative colitis symptoms returned. The flare-up coincided with a drop in the number of worm eggs in the man's stool, from 15,000 eggs per gram to less than 7,000, the researchers observed. The patient dosed himself with another 2,000 whipworm eggs. His symptoms retreated.

More worms, more mucus

The researchers analyzed biopsy samples from colonoscopies in 2008 and 2009, one during a symptom flare-up and one when all was clear. They found that during the colitis outbreak, 70 percent of a particular type of immune cell, called the T helper cell, produced an inflammatory protein called interleukin-17. Only 1 percent produced interleukin-22, a protein that is known to stimulate mucus production in mice. In less-inflamed areas, the T cells produced more interleukin-22.

Intrigued, the researchers checked the inflamed bowel for mucus. Sure enough, in inflamed areas, the intestinal lining was dry. In 2009, when symptoms receded, the same areas were flush with mucus.

Whether the researchers compared symptom-free times with inflammatory bouts, or they compared inflamed areas with non-inflamed areas during the same colonoscopy, increased interleukin-22 production always coincided with healing, Loke said.

The researchers don't know why the worms trigger interleukin-22 production, but it may not be intentional, Loke said.

"I think what's happening is the immune response is trying to expel the worms and also trying to repair the damage that the worms are causing in the gut," he said. "That response may actually improve colitis, because it's increasing mucus production and it's increasing the turnover of the epithelial cells in the gut."

Use as directed

Because the study only investigated one patient, it's no substitute for clinical trials on multiple subjects who don't know what treatments they're receiving, said Joel Weinstock, a biomedical researcher at Tufts University, who was not involved in the study.

"It's not definitive proof that the agent made him better," Weinstock told LiveScience. "It's just suggestive."

However, Weinstock said, the study was a "well-done," novel investigation, and the discovery of interleukin-22's role opens up a new line of research.

"The worms apparently have several tricks up their sleeve, so to speak, for modulating and regulating the immune system," Weinstock said. "Interleukin-22 hasn't been on the radar screen."

Tests of the similar worm T. suis are ongoing in the United States and Europe, Weinstock said. That research goes beyond inflammatory bowel disease into other autoimmune disorders like food allergies and multiple sclerosis, he said.

Nonetheless, both Loke and Weinstock advise against patients rushing out in search of T. trichiura or other worms. The worms live and lay eggs in human feces, which can also transmit diseases like hepatitis.

"There's no safe way of getting exposed to it at this point," Weinstock said. "All of these things should be done with the aid of a doctor and carefully thought through, not by indiscriminately seeking exposure."

- The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites

- Extremophiles: World's Weirdest Life

- Mind-Controlling Parasites Date Back Millions of Years

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus