Hopes Dashed: Women Don't Generate New Eggs

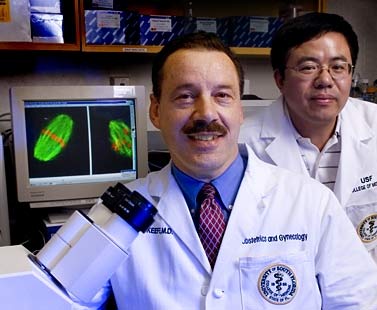

Since the 1950s, women were told all the eggs they'd ever carry were created before they were born. A couple years back, however, research on mice suggested eggs might be generated later in life. That gave a glimmer of hope to women who suffered infertility problems. But the hope has apparently been dashed by a new study led by University of South Florida biologists Lin Liu and David Keefe. The dogma that a woman's egg-making days are limited was challenged by a team lead by Harvard reproductive endocrinologist Jonathan Tilly who published studies conducted on mice in 2004 and 2005. "The implications of Tilly's group's work may be less exciting for human fertility if the work done by Liu's team is confirmed by similar or alternate approaches," said Emre Seli, a Yale University molecular gamete biologist who was not involved in the research. After Tilly's research on female mice producing eggs later in life was published, fertility specialist Keefe said women came into his office with a false hope about their future fertility, assuming that scientists were well on their way to regenerating eggs. Still, doctors have observed in IVF (in vitro fertilization) clinics that women do not generate new eggs later in life. "In Tilly's articles, there was a bit of overselling the concept," said Keefe, a physician scientist. "It was not really fair to the patients." To determine when eggs are made, Liu and colleagues studied the genes in ovaries of 12 women aged 28 to 53 and compared those with genes of female fetuses. In the fetuses, the researchers pinpointed genes responsible for egg production, but in the adult women, the scientists found no evidence of such "oogenesis" genes. The results were published in the March issue of the journal Developmental Biology. In reaction to Liu's results, Tilly wrote a response in a different journal, Cell Cycle, stating in its April issue, "It is disappointing to see arguments against the possibility of postnatal oogenesis in mammals still being drawn using solely an 'absence of evidence' approach." Yet ovarian physiologists, including Janice Bahr at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, think differently. Bahr, who was not involved in any of the studies, found Liu's work meticulous and solid. She did, however, agree with Tilly's desire to challenge old ideas with new technology. From the 1850s until 1951, scientists assumed women made new eggs during sexual maturation. But research published in 1951 by biologist Solly Zuckerman changed people's thinking when he showed that a female is born with all of her eggs. "Because of the new techniques available to us, it is always good for science to reexamine theories," Bahr said. "But then when we do examine them, we really need to present rigorous data to confirm that a long held theory isn't true. With our new tools, we can ask: Will this theory established in 1950 still stand today?" she said. "The Liu paper has confirmed Zuckerman's research."

- Sniff and Swim: How Sperm Find Eggs?

- The Sex Quiz: Myths, Taboos, and Bizarre Facts?

- A Brief History of Human Sex?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.