Tiny Creatures Are Ocean's 'Vacuum Cleaners'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Small blob-like creatures may be the ocean's most efficient feeders, a new study suggests.

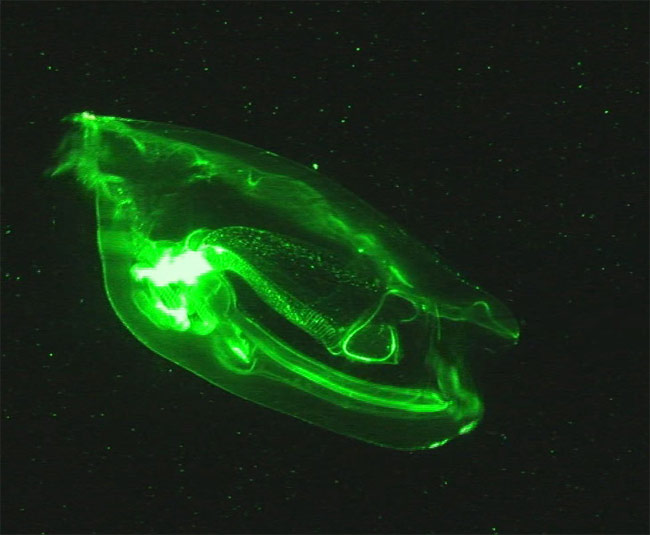

The salp, a 5-inch (13-centimeter)-long , barrel-shaped organism that resembles a streamlined jellyfish, lives in mid-ocean waters where it filters the seawater for food particles.

"We had long thought that salps were about the most efficient filter-feeders in the ocean," said study researcher Larry Madin, director of research at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.

But the new results show these animals can consume particles that span a huge size range, or about four orders of magnitude, from a fraction of a micrometer to a few millimeters. If sized up that range would be like eating everything from a mouse to a horse, Madin said.

The finding, published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, "implies that salps are more efficient vacuum cleaners than we thought," said study researcher Roman Stocker of MIT.

Mucus trap

Salps, which can live for weeks or months as single globs or chains of 100 or more individuals, swim and eat in rhythmic pulses, each of which draws seawater in through an opening at the front end of the animal. A nanometer-scale mucus net captures the food particles, mostly phytoplankton, which end up in the gut where they get digested.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The mucus net "starts from the mouth and extends backwards, like a bag in a vacuum cleaner," Stocker told LiveScience.

Until now, it was thought the 1.5-micron-wide holes in the mesh meant only particles larger than that got captured, while smaller particles would slip through the mucus net. (For comparison, the diameter of a human hair is about 100 microns.)

But a mathematical model suggested salps somehow might be capturing food particles smaller than that, said study researcher Kelly Sutherland, then working on her Ph.D. at MIT and WHOI.

In the laboratory at WHOI, Sutherland and her colleagues offered salps food particles of three sizes: smaller, around the same size as, and larger than the mesh openings.

"We found that more small particles were captured than expected," said Sutherland, now a post-doctoral researcher at Caltech. "When exposed to ocean-like particle concentrations, 80 percent of the particles that were captured were the smallest particles offered in the experiment."

Salp survival

The finding helps explain how salps can survive in the open ocean where the supply of larger food particles is low.

In addition, the results reveal the importance of the salps in carbon cycling. Scientists believe its waste material may help remove carbon dioxide (CO2) from the upper ocean and the atmosphere.

After eating both small and large particles, the animals release waste that consists of these particles packed into larger, denser globs.

The larger and denser the carbon-containing pellets, the sooner they sink to the ocean bottom. "This removes carbon from the surface waters, and brings it to a depth where you won't see it again for years to centuries," Sutherland said.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the WHOI Ocean Life Institute.

- Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures

- The Truth Behind Global Jellyfish Swarms

- Images: Rich Life Under the Sea

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus