Gulp! Long-Necked Dinosaurs Didn't Bother Chewing

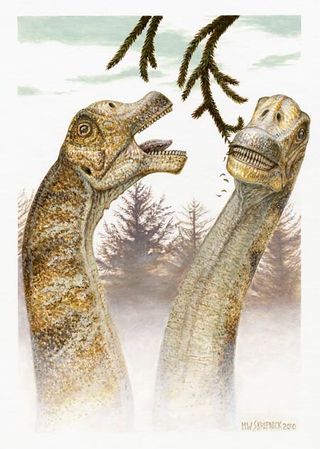

A mom's wise words about chewing your food likely got lost on a giant, long-necked dinosaur that lived about 105 million years ago in North America. That's according to analyses of four skulls from a newly identified dinosaur species.

"They didn't chew their food; they just grabbed it and swallowed it," said study team member Brooks Britt, a paleontologist at Brigham Young University.

Paleontologists discovered the four skulls, two of which whose bones were fully intact, from a quarry in Dinosaur National Monument in eastern Utah. Now called Abydosaurus mcintoshi, the dinosaur species is a type of sauropod (long-necked plant-eaters) and is most closely related to Brachiosaurus that lived 45 million years earlier.

No time for chewing

While scientists have suggested sauropods didn't chew their foods, there hasn't been much hard evidence to examine this premise. Just about 10 percent of the 120-plus sauropod species have been found with complete skulls. And so most of what scientists know about these herbivores comes from the neck down.

With the skulls from Abydosaurus, the research team suspects sauropods' small heads, which are just about one two-hundredth the volume of their bodies, might explain why they skipped chewing.

"If you have a tiny skull and you're trying to feed a big body, you're wasting time if you're trying to process the food in your mouth," said Jeffrey Wilson of the Museum of Paleontology and Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Michigan.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That's especially true for sauropods, which are the largest animals to ever plod the earth. Abydosaurus was likely a bit smaller than Brachiosaurus, which stretched more than 65 feet (20 meters) and weighed nearly 20 tons.

During the Late Jurassic Period about 150 million years ago, sauropod fossils suggest the beasts sported both broad-crowned and narrow-crowned teeth. That changed by the end of the dinosaur age, when all sauropods likely had narrow, pencil-like teeth.

Abydosaurus had teeth that seemed to be in transition from the broad shape to the narrowest ones. And while its teeth were narrower than those of Brachiosaurus, its skull looked pretty much the same.

Tooth replacement

Sauropods also replaced their teeth continuously. The narrower the teeth, the more can be packed into the jaws and the faster they were replaced, Wilson said. Abydosaurus had teeth that were as broad as those that replaced every two months or so, though the researchers haven't looked at this replacement rate yet.

To explain the rapid tooth replacement, Wilson says Abydosaurus may have been snagging abrasive foods. In addition, the dinosaurs may have been low browsers, where they would pick up sediment and other silica-containing material that can wear down teeth quickly.

Like Brachiosaurus and other sauropods, Abydosaurus didn't have any of the bells and whistles present in savvy plant-eating dinosaurs.

"For some reason sauropods don't develop any of the tricks that other dinosaurs developed for eating plants," Wilson told LiveScience. For instance, Triceratops and some duck-billed dinosaurs have pointed beaks to help cut vegetation. They also had cheeks, like us, where they could store food while they were processing it in their mouths before swallowing, and they developed batteries of teeth to process food.

"So sauropods could have evolved this machinery but didn't. Our explanation [is that] these adapatations are not good evolutionary investments for an animal whose skull is so small compared to rest of its body," Wilson said. "The sauropod strategy is to bite the food, maybe bite it once more, and then swallow it and let it digest in your gut."

The discovery is detailed in the most recent issue of the journal Naturwissenshaften.

- 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Images: Dinosaur Fossils

- Toothy Dinosaur Mowed Earth Like a Cow

Jeanna served as editor-in-chief of Live Science. Previously, she was an assistant editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Jeanna has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland, and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Most Popular