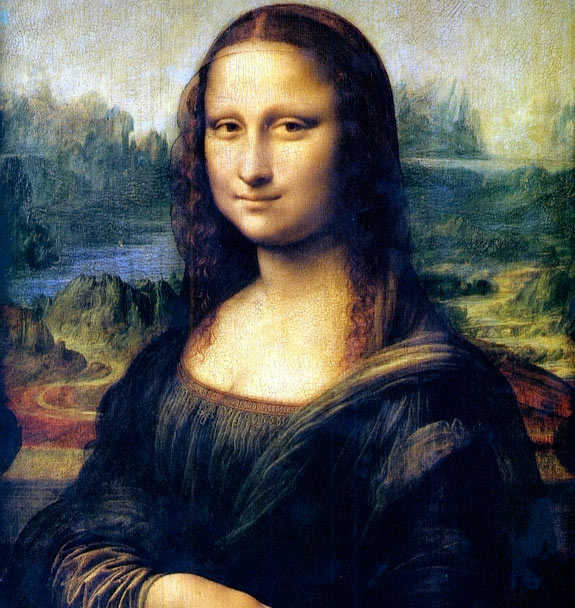

Mona Lisa Turns 500, and Other Unproved 'Theories'

Maybe she's smiling because she found the secret to immortality.

Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa," widely considered the world's most recognizable work of art, turns 500 this year. Maybe.

The sitter's enigmatic smirk is just one of the mysteries that historians, scientists and conspiracy theorists have been debating since the artist touched his last brushstroke to the canvas.

Even the year it was painted is not known for sure. It is widely believed to have been finished in 1506, but experts say that's no more than a good guess. Toting it with him his entire life, da Vinci likely touched it up in subsequent years.

What's the fuss?

The painting currently hangs in the Louvre Museum in Paris. It is set behind a wall of bulletproof glass and watched over by armed guards.

So what's all the fuss about?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There's no reason for it," said Frank Fehrenbach, Renaissance expert and professor of art history at Harvard University. "It is a beautiful portrait, but only historical coincidences have made it so famous."

The Romantic Movement in the 19th century had a lot to do with popularizing the work, Fehrenbach said.

"Romantic writers created the popular image of the 'Mona Lisa,'" Fehrenbach told LiveScience. Because of her bemused smile, "they said she must hold secrets, that she was the quintessential ‘femme fatale.' With all of these new ideas about the Renaissance being discussed, the 'Mona Lisa' became the symbol of that."

The decisive moment

A brief absence from the Louvre made her even more famous.

"The theft in 1911 was a decisive moment in her history," Fehrenbach explained. "After she was recovered and returned triumphantly to the museum in 1913, she became its temple icon."

Since then, the public has held an unwavering fascination with the "Mona Lisa," and her mystique has only snowballed with the emergence of various popular theories over the years. "The Da Vinci Code" (Doubleday, 2003), Dan Brown's wildly successful novel, has helped out in no small part, with the painting figuring prominently in its riveting opening chapters. A film version will be released on May 19.

Like Brown's protagonist, some are convinced that da Vinci filled the "Mona Lisa" with religious and scientific symbolism, including the golden ratio—a very precise measurement said to appear mysteriously throughout the natural world—in drawing the sitter's face. Experts are quick to dismiss this notion, and most other "theories" on the painting, as the products of overactive imaginations.

"There is no documented evidence that da Vinci had any kind of intention to use the golden ratio within the 'Mona Lisa,' even though he certainly had knowledge of it," said Mario Livio, astrophysicist and author of "The Golden Ratio: The Story of PHI, The World's Most Astonishing Number" (Broadway, 2003).

"Art historians will sometimes treat paintings with a meter stick to find some kind of hidden geometry," Fehrenbach agreed. "But you can always find something if you're looking."

Science and art

There is plenty of science going on in the painting, Fehrenbach noted, just not the hidden, mysterious kind that people would like to believe.

Most evident is da Vinci's fascination with the earth sciences.

"The sitter's background is a rough, primordial landscape with very little else. This technique was very new at the time," he said. "It demonstrates da Vinci's interest in erosive forces and hydrogeology, which we know he would investigate further."

And what about that half-smile? Fehrenbach has his own theory.

"It's quite possible that she became bored during the long sitting process and da Vinci wanted to reflect that in the painting," he said.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus