An ancient member of the human family has gotten a digital facelift, and the new mug looks more ape-like than scientists previously thought.

The new reconstruction suggests the large brains and flatter faces characteristic of modern humans did not appear in our lineage until much later in our history.

“For how many years now, people have been using this [skull] and the numbers may not be very meaningful,” said Timothy Bromage, an anthropologist at New York University who led the new reconstruction effort.

Controversial skull

The skull in question, KNM-ER 1470, is arguably the most controversial fossil in the history of anthropology. When it was first discovered in northern Kenya in 1972, it was initially dated to nearly 3 million years old. Yet the skull—which scientists painstakingly pieced together from hundreds of bone fragments—had a large brain and a flat face, features reminiscent of modern humans but completely unlike any hominid known to exist at the time.

So troublesome was the skull that famed paleo-anthropologist Richard Leakey, the leader of the team that discovered it, once told reporters: "Either we toss out this skull or we toss out our theories of early man. It simply fits no models of human beginnings."

Leakey later revised the age of KNM-ER 1470 to 1.9 million years, but even then, some scientists have argued that the skull’s features are much more humanlike than its contemporary, Homo habilis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other scientists claim Homo rudolfensis, the name that some anthropologists have assigned to the skull, should be identified as a H. habilis and not a separate species at all. Whether either of these hominids was a direct ancestor of humans is still an open question.

Impossible face

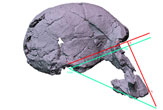

For the new reconstruction, the researchers used a combination of a deformable cast and computer-generated models to create replicas of KNM-ER 1470’s skull that could be shaped.

Bromage said the original reconstruction relied on preconceptions about how early humans looked that are now known to be incorrect. The result, he said, was a skull that shared several features in common with modern humans, including a relatively flat face and a large brain case.

“It’s always been an outlier in every study ever performed on [hominid] brain sizes” from that period, Bromage said.

Bromage said his team’s reconstruction includes biological principles not known at the time of the skull’s discovery, which state that a mammal’s eyes, ears and mouth must be in precise relationships relative to one another.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re a rat, a kangaroo, an elephant, a human or a dog—their [facial features] are all organized to a very specific architectural plan,” Bromage said.

For example, Bromage said, take any mammal and draw an imaginary line from the last permanent molar in its jaw that extends towards the opening of the ear and out the center of the eye socket. The angle of that line should be around 45 degrees.

“What this does is distribute the senses in a very specific way,” Bromage explained.

In the original KNM-ER 1470 reconstruction, this angle was between 60 and 75 degrees, Bromage said. “It was absolutely incompatible with life,” he said. “The jaw would have been positioned so far back in the skull that there would have been no room for an airway or esophagus. It couldn’t breathe or eat.”

Bromage presented his team’s findings at the annual meeting of the International Association for Dental Research last week and is submitting the results to a scientific journal for peer review later this year.

Smaller brain too?

The new reconstruction suggests H. rudolfensis’ jaw jutted out much farther than previously thought. The researchers say the cranial capacity of a hominid can be estimated based on the angle of the jaw’s slope and they have downsized KNM-ER 1470’s cranial capacity from 752 cubic centimeters to about 526 cc. (Humans have an average cranial capacity of about 1,300 cc.)

But not everyone agrees that brain size can be inferred from jaw protrusion. Biological anthropologist Robert Martin, of the Field Museum in Chicago, said the researchers “may well be right” in their reconstruction of the face, but said the researchers’ claims about being able to estimate cranial capacity from facial features are “crazy.”

“What they’re claiming is you stick the face out, and because the face sticks out more the brain capacity has to be less. I don’t follow that at all,” said Martin, who is an expert on hominid skulls and who was not involved in the study.

“They haven’t changed the skull at all; they’ve simply rotated the face outwards,” Martin added.

Martin also disputes the claim that H. rudolfensis’ large cranial capacity made it stand out among ancient hominids. Martin points out that a 1.6 million-year-old Homo erectus skeleton known as “Turkana Boy” had a cranial capacity of about 900 cc.

“At 1.9, you’ve got [H. rudolfensis] with [a cranial capacity] of 750 cc, and at 1.6 you’ve got 900 cc. I don’t have a problem with that,” Martin said.

If confirmed, KNM-ER1470’s new cranial capacity would be comparable to that of H. habilis. “Now it’s no longer an outlier,” Bromage said. “It’s just part of the gang.”

It would also suggest humans developed their characteristically large brains and flatter faces at least 300,000 years later than previously thought, perhaps as recently as 1.6 to one million years ago when H. erectus and another later hominid, Homo ergaster, lived.

- Top 10 Missing Links

- Fear of Snakes Drove Pre-Human Evolution

- All About Evolution

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus