What Made Ancient Hominins Cannibals? Humans Were Nutritious and Easy Prey

Around 900,000 years ago in what is now Spain, the human relative Homo antecessor hunted and ate others of their kind, leaving behind the oldest known evidence of cannibalism.

And new analysis of these ancient remains hints that these hominins were cannibals because human flesh was nutritious — and that humans were easier targets than other types of large prey. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

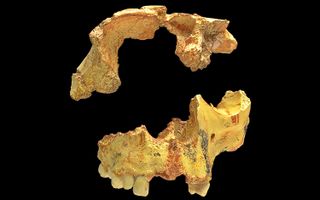

Bones of seven H. antecessor individuals at the Spanish archaeological site Gran Dolina displayed distinctive signs that they were cannibalized: human tooth marks, cut marks, and fractures to expose the marrow, researchers reported in a new study. Those bones were mixed with bones representing nine other mammal species; 22 individuals that also had been butchered and eaten.

H. antecessor seemingly had plenty of prey to choose from, so why were humans on the menu? To find out, the researchers used computer models to calculate how many calories H. antecessor would require per day. Then, they estimated the caloric payoffs of various animals — including humans — and the energy that would have been needed to catch them. They speculated that H. antecessor hunters would choose their prey based on a balance: the most calories for the least effort.

Counting calories

Previous studies showed that while humans provided a moderately nutritious meal, there were other animals that packed far more calories per bite, the scientists reported. But if hunters had to spend less energy to catch human prey, they would benefit even if the caloric count of human flesh was lower, according to the study.

The researchers found that while human bones were the most represented, they accounted for less than 13% of the hunters' caloric requirements; most of which came from rhinos, deer and horses. But unlike humans, those animals come at a very high energy cost.

"Our analyses show that Homo antecessor, like any predator, selected its prey following the principle of optimizing the cost-benefit balance," lead study author Jesús Rodríguez, a researcher with the Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH), in Spain, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Considering only this balance, humans were a 'high-ranked' prey type. This means that, when compared with other prey, a lot of food could be obtained from humans at low cost," Rodríguez said.

The findings were published online in the June 2019 issue of the Journal of Human Evolution.

- Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans

- Cannibal Nutrition and Self-Colonoscopies Win Accolades at the 2018 Ig Nobels

- Photos: Newfound Ancient Human Relative Discovered in Philippines

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.