Maybe Bigfoot Was a Dinosaur, If These Fossils Are Any Indication

While basketball player LeBron James' shoe size (15) is pretty big, it's nowhere near the considerable foot size of the dinosaur with the largest feet on record, a new study finds.

That honor goes to a long-necked dinosaur of "enormous proportions" that lumbered around about 150 million years ago in what is now Wyoming, the researchers said.

At nearly 3.2 feet (1 meter) long, "it is the largest dinosaur foot that was ever found, which must have belonged to one of the largest land animals ever," study co-researcher Emanuel Tschopp, a postdoctoral fellow at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, told Live Science. [Titanosaur Photos: Meet the Largest Dinosaur on Record]

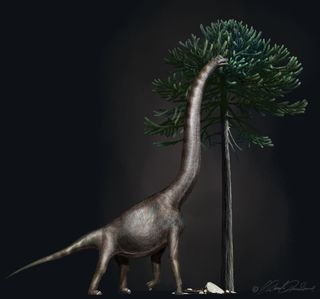

Researchers found the jumbo-size foot fossils in 1998, buried underneath the tail of a long-necked Camarasaurus dinosaur. These fossils are part of the Morrison Formation — a rocky expanse known for its Late Jurassic period fossils, especially its sauropods (long-necked herbivorous dinosaurs that walked on all fours), such as Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus. Though the scientists aren't sure what species the fossils came from, it's likely a close relative of Brachiosaurus, which made a cameo in the 1993 film "Jurassic Park."

During the dig, the paleontologists found "several individuals of various ages and from at least three different species," Tschopp said. "This foot definitely belonged to the largest individual preserved in this quarry, but unfortunately, nothing else of it was found."

The foot — a left hindfoot — was so massive that the paleontologists from the 1998 dig nicknamed it "Bigfoot." But despite its gargantuan size, the foot hadn't been described in detail until now, said lead study researcher Anthony Maltese, curator of the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center in Woodland Park, Colorado, who also took part in the 1998 excavation.

To investigate, Maltese and his colleagues used a 3D-scanning technique to take precise measurements of the mystery dinosaur's foot and then compared those with the foot bones of other sauropods. They found that the beast was closely related to Brachiosaurus and that it likely stood about a whopping 13 feet (4 m) tall at the hip.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: The most famous Bigfoot sightings

Given the dinosaur's fantastic foot size, it's safe to call it a titanosaur — the largest group of sauropod dinosaurs — which includes the 122-foot-long (37 m) Patagotitan and the 115-foot-long (35 m) Argentinosaurus.

The newly described foot bones are slightly larger than those of the long-necked Giraffatitan sauropod dinosaur and "considerably larger than those of Dreadnoughtus, which was reported to be one of the largest sauropods ever found." Even so, it's by no means the largest dinosaur on record, the researchers wrote in the study. That's because foot size doesn't directly equate to body size.

"Some of the largest sauropods such as Argentinosaurus or Patagotitan do not preserve pedal [foot] material, but have femur lengths that considerably exceed our estimate for [the newly discovered dinosaur]," the researchers wrote in the study. For instance, the mystery dinosaur has an estimated femur length of 6.7 feet (2 m), while Argentinosaurus had a femur length of 8.3 feet (2.5 m) and Patagotitan's was 7.7 feet (2.3 m), the researchers said.

The finding also reveals that large brachiosaurs and their close relatives inhabited huge geographical swaths 150 million years ago, from eastern Utah to northwestern Wyoming.

"This is surprising," Tschopp said in a statement. "Many other sauropod dinosaurs seem to have inhabited smaller areas during that time."

The study was published online today (July 24) in the Journal of Life and Environmental Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular