In Photos: Carved Human Skulls Discovered at Ritual Site

Göbekli Tepe

An aerial view of Göbekli Tepe, an 11,000-year-old Stone Age site in what is now Turkey. In excavations since 1995, archaeologists have discovered round stone buildings, pillars and elaborate animal carvings at this site, all made with nothing more than flint tools. Göbekli Tepe was built at a time when Neolithic people were transitioning from migratory hunter-herder lifestyles to more sedentary agricultural communities. [Read full story about the carved skulls found at the site in Turkey]

Sliced Skull

Now, researchers have discovered a new mystery at Göbekli Tepe: Seven skull fragments from three different skulls, each marked with deep cuts like this one, which ran down the middle of the top of the head. The cuts were made shortly after death.

Mysterious carvings

A detailed view of some of the skull fragments from Göbekli Tepe. These fragments were found mixed in a loose array of soil, animal bone fragments, flint fragments and human bone pieces inside the stone structures at the Stone Age site. One skull sported a 0.2- inch (5 millimeter) drill hole (upper right). The position of the cuts and hole suggest that they might have been used to attach cords to hang the skulls or decorate them with objects like feathers.

Deep Grooves

The bone fragments of a skull found at Göbekli Tepe sport cut marks, illuminated in red on the underlying illustration. Other Stone Age sites in Anatolia have revealed evidence of "skull cults," or traditions involving the use of the skulls of the recently deceased. Nowhere else have cuts like this been observed, however.

Placement of the carvings

A schematic showing the position of the carving marks seen on the bone fragements discovered at Göbekli Tepe. The cuts were sharp-edged, indicating they were made when the bone was still fresh and somewhat elastic — in other words, not long after death. Skull 1 also had remnants of red ochre powder on the bone.

Stone Age Art

A carved stone pillar from Göbekli Tepe. Some pillars at the site are up to 13 feet (4 meters) tall. As evidenced by this carving, the Neolithic people who built this site were very skilled with flint tools. That makes the crude carvings on the skulls something of a mystery. Perhaps, archaeologists say, the skulls were carved so crudely as a way to stigmatize the person after death. Or they may have simply been practical cuts for displaying the skulls.

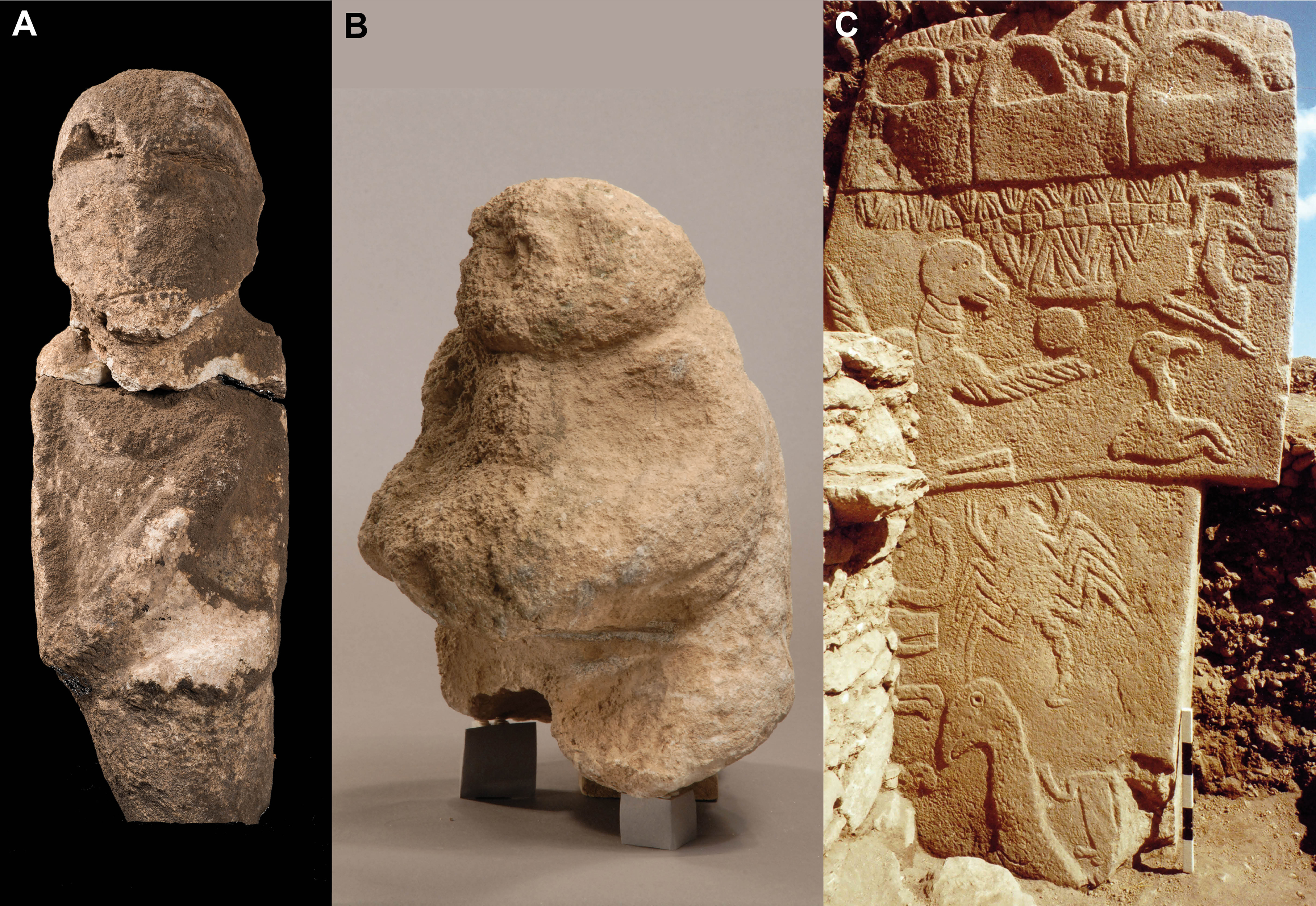

Gobelki Tepe Carvings

Three carvings from Göbekli Tepe that hint at the importance of skulls to the site. On the far left, a 23-inch (60 cm) tall statue deliberately broken at the neck. In the middle, a 10- inch (26 cm) tall gift bearer holds a human head in his hands. On the right, a carved pillar shows a headless individual with an erect penis and one arm raised (lower right portion of the carving).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mysterious Place

The ritual complex at Göbekli Tepe. This site shows no sign of human habitation or domestic life, and archaeologists have yet to find formal burial sites — though they have found nearly 700 human bone fragments from men, women and children. The kind of rituals conducted here remain a mystery.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus