Photos: Migrants to Ancient Rome Uncovered in Cemetery

Four immigrants, including three adult men and a young teenager, were found buried in cemeteries outside of Rome. Analyses of the teeth suggested the individuals lived during the first to third centuries A.D., and are considered the first individuals identified as migrating to the city during the Roman Imperial era. Here’s a look at the excavated skeletons and study findings. [Read full story about the Roman migrants]

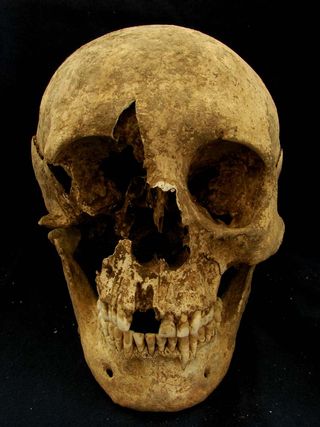

Ancient migrant

The partial skull of a man between the ages of 35 and 50, found in a cemetery outside of Rome. This man lived and died in the capital city of the Roman Empire during the first to third centuries A.D., but he wasn't born there. A new isotope analysis of the teeth of this and other skeletons reveals the first known individual migrants to Rome during this era.

Isotopes, or variations of elements, can reveal where a person spent their early years, when tooth enamel was developing. This man's enamel was high in strontium isotopes, suggesting he grew up somewhere with old geology (as opposed to most of Italy's young rocks). Other isotopes point to the Alps or the islands of the Tyrrhenian Sea as a possibility. (Credit: Kristina Killgrove)

Long-distance traveler

The skull of a second middle-aged man who was probably a migrant to Rome during the Imperial era. Isotopes in this man's teeth suggested that he may have hailed from the Alps or Italy's Tyrrhenian islands, or some other spot with old, non-volcanic geology. Researchers can't know if this person was a voluntary migrant or a slave brought to Rome by force. His burial, however, suggests that he was a low-status person.(Credit: Kristina Killgrove)

Cemetery Map

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A map showing two cemeteries outside of Rome where researchers found evidence of migrants to the city. Casal Bertone and Castellaccio Europarco were burial grounds for the metropolis, which was home to perhaps a million people during the Imperial Era. Burials took place outside the city walls for reasons of hygiene and religion. (Credit: Killgrove K, Montgomery J (2016) All Roads Lead to Rome: Exploring Human Migration to the Eternal City through Biochemistry of Skeletons from Two Imperial-Era Cemeteries (1st-3rd c AD). PLoS ONE 11(2): e0147585. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0147585)

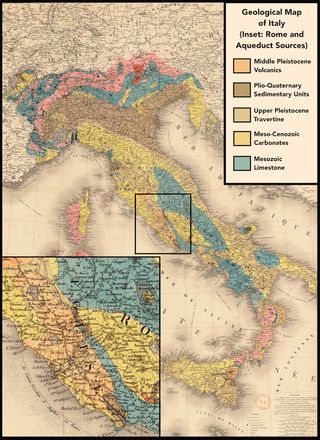

Geology of Italy

A map showing the types of rocks underlying Italy. Geology can tell researchers where a person came from. In the first years of life, when the tooth enamel is forming, molecular signatures from food and water end up incorporated into the teeth. Some of these signatures, called isotopes, originate in the rocks and soil. Killgrove and her colleagues studied isotopes of the element strontium to pinpoint newcomers to Rome. (Credit: Killgrove K, Montgomery J (2016) All Roads Lead to Rome: Exploring Human Migration to the Eternal City through Biochemistry of Skeletons from Two Imperial-Era Cemeteries (1st-3rd c AD). PLoS ONE 11(2): e0147585. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0147585)

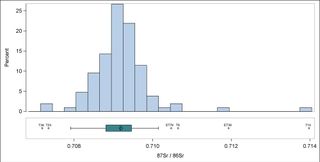

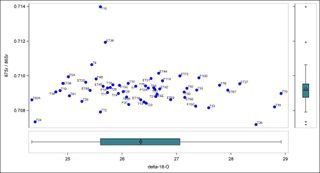

Strontium graph

This graph shows strontium isotope ratios for Imperial-era skeletons buried in two cemeteries outside of Rome. Most of the skeletons are clustered between 0.708 and 0.710, reflecting the strontium isotopes underlying Rome itself. But outliers on the graph — T36, T24, ET76, T8, ET38 and T15 — represent skeletons that may have belonged to migrants. (Credit: Killgrove K, Montgomery J (2016) All Roads Lead to Rome: Exploring Human Migration to the Eternal City through Biochemistry of Skeletons from Two Imperial-Era Cemeteries (1st-3rd c AD). PLoS ONE 11(2): e0147585. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0147585)

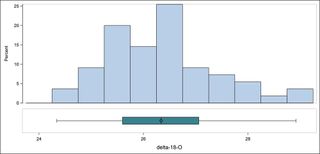

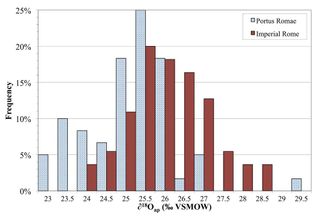

Oxygen graph

This graph shows the oxygen isotope ratios of skeletons from two cemeteries outside of Rome. Oxygen isotopes mostly reflect the origin of the water people drink, which can capture information about the climate, elevation and rainfall of the place of their birth. (Credit: Killgrove K, Montgomery J (2016) All Roads Lead to Rome: Exploring Human Migration to the Eternal City through Biochemistry of Skeletons from Two Imperial-Era Cemeteries (1st-3rd c AD). PLoS ONE 11(2): e0147585. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0147585)

Comparing oxygen

A graph comparing the oxygen ratios of Imperial Roman skeletons with skeletons found in the Isola Sacra cemetery of the city of Portus Romae, which is on the coast of Italy southwest of Rome. The differences in the values reflects the different origins of the drinking water and food of these two populations. (Credit: Killgrove K, Montgomery J (2016) All Roads Lead to Rome: Exploring Human Migration to the Eternal City through Biochemistry of Skeletons from Two Imperial-Era Cemeteries (1st-3rd c AD). PLoS ONE 11(2): e0147585. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0147585)

Strontium and Oxygen

A plot of strontium and oxygen ratios of people buried in Imperial Roman cemeteries outside of the city. A glance at this graph reveals outliers like T15, a middle-age man with an unusually high strontium ratio, or T36, an adolescent of unknown gender with a high oxygen isotope ratio and low strontium. This teen appears to have come from an arid climate with limestone or basalt geology, perhaps North Africa. (Credit: Killgrove K, Montgomery J (2016) All Roads Lead to Rome: Exploring Human Migration to the Eternal City through Biochemistry of Skeletons from Two Imperial-Era Cemeteries (1st-3rd c AD). PLoS ONE 11(2): e0147585. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0147585)

Teen migrant?

The frontal skull bone of skeleton T36, which belonged to a teenager between the ages of 11 and 15. This person had an isotope value suggesting that they were born somewhere with an arid climate and geology quite different than Rome's. One possible match, Killgrove and her colleagues reported, was North Africa. (Credit: Kristina Killgrove)

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular