Higgs Boson to the World Wide Web: 7 Big Discoveries Made at CERN

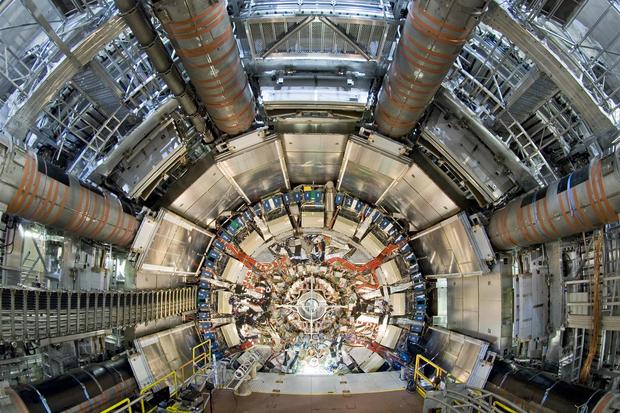

The world's biggest atom smasher, where monumental discoveries such as the detection of the once-elusive Higgs boson particle and the creation of antimatter have occurred, is celebrating its 60th anniversary today (Sept. 29).

Founded in 1954, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or CERN, located near Geneva on the French-Swiss border, contains some of the largest and most advanced particle accelerators in the world.

In honor of the lab's anniversary, here are a few of the greatest discoveries made at CERN over the past six decades. [Wacky Physics: The Coolest Little Particles in Nature]

1. The 'God particle'

The physics world erupted in excitement in July 2012, when scientists using the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN announced they had detected a particle that looked to be the so-called Higgs boson.

In the 1960s, British physicist Peter Higgs hypothesized the existence of a field through which all particles would be dragged — like marbles moving through molasses — giving the particles mass. Higgs thought this field would have a particle associated with it — one that is thought to give all other particles their mass. This particle became known as the Higgs boson. It was nicknamed the "God particle" after a 1993 book by physicist Leon Lederman and science writer Dick Teresi, but many physicists — including Higgs himself — reject the term as being sensational.

In 2012, after a decades-long hunt, two experiments at the LHC detected a new elementary particle weighing about 126 times as much as a proton, the positively charged particle found in the nucleus of an atom. Less than a year later, after physicists had collected two-and-a-half times more data inside the LHC, the researchers confirmed that the newfound particle was, indeed, the Higgs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The discovery of the Higgs boson represents the final piece of the puzzle in the Standard Model of particle physics, a theory that describes how three of the four fundamental forces — electromagnetic, weak and strong nuclear forces — interact at the subatomic level (but does not include gravity). Peter Higgs and Belgian physicist Francois Englert were awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 2013 for their prediction of the Higgs boson's existence.

2. Weak neutral currents

In 1973, one of the first major discoveries came out of CERN: the detection of so-called weak neutral currents, inside a device called the Gargamelle bubble chamber.

Weak neutral currents are one way that subatomic particles can interact via the weak force, one of the four fundamental interactions in particle physics. The discovery of neutral currents helped unify two of the fundamental interactions of nature (electromagnetism and the weak force) as the electroweak force.

Theoretical physicists Abdus Salam, Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg predicted weak neutral currents in the same year that scientists at CERN confirmed these currents' existence. The theorists were awarded a Nobel Prize for their work in 1979.

3. W and Z bosons

In 1983, a decade after CERN scientists detected weak neutral currents, they discovered the W and Z bosons, elementary particles that mediate the weak force. The two W bosons (W+ and W-) have the same mass but opposite electrical charges, while the Z boson has no charge. Their discovery was a major boon to the Standard Model.

Using a particle accelerator called the Super Proton Synchrotron, particle physicists Carlo Rubbia and Simon van der Meer led a team that found proof of the bosons in experiments called UA1 and UA2. The two scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in physics the following year.

4. Light neutrinos

In 1989, CERN scientists determined the number of families of particles containing what are known as light neutrinos. Uncharged elementary particles with very little or no mass, neutrinos only rarely interact with other particles, and thus are sometimes called "ghost particles."

The discovery of these light, ghostly particles was made at the Large Electron-Positron Collider (LEP), using an instrument called the ALEPH detector. The findings agreed well with the Standard Model. [Twisted Physics: 7 Mind-Blowing Findings]

5. Antimatter

Antimatter consists of particles that have the same mass as a particle of matter but an opposite electrical charge (as well as other properties). When matter and antimatter combine, they annihilate each other, releasing enormous amounts of energy and producing high-energy particles such as gamma-rays.

In 1995, CERN scientists succeeded in creating a form of antimatter called antihydrogen, a negatively charged version of hydrogen, in the PS210 experiment at the Low Energy Antiproton Ring. However, the antimatter collided with matter and was annihilated before scientists could study it.

In 2010, CERN's Antihydrogen Laser Physics Apparatus (ALPHA) team created and corralled antihydrogen for about a sixth of a second, and in 2011, they maintained the antimatter for more than 15 minutes.

6. Charge parity violation

One of the mysteries of cosmology is how matter exists despite the presence of antimatter in the universe, since the two tend to annihilate each other. The answer has to do with a kind of asymmetry between matter and antimatter.

At first glance, the laws of physics should be the same if a particle were replaced with its antiparticle — a concept known as charge parity symmetry (CP-symmetry). But physicists at CERN were able to show that charge parity is violated.

In 1964, nuclear physicists James Cronin and Val Fitch found the first evidence that CP-symmetry could be broken — a discovery for which they won the Nobel Prize in 1980. But the final evidence for the violation of this symmetry came in 1999, with the NA48 experiment at CERN, and in a parallel experiment at the U.S. particle physics facility Fermilab, in Batavia, Illinois.

7. World Wide Web

Particle physics aside, CERN is the birthplace of one of the world's best-known inventions: the World Wide Web (WWW). Invented by British scientist Tim Berners-Lee at CERN in 1989, the Web was originally designed as a way for scientists at institutions around the world to share information.

The first website described the World Wide Web project, as well as how to use it to access documents or set up a computer server. Berners-Lee hosted the Web on his NeXT computer, which is still located at CERN.

The WWW software was put into the public domain in April 1993, and was made freely available so anyone could run a Web server or use a basic browser. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.