Weirdest Worm Ever? Clawed Creature Finds Its Family Tree

When researchers first discovered the fossil worm Hallucigenia in the 1970s, they were so perplexed they identified its head as its tail and its legs as its spines.

Now, this 505-million-year-old worm, whose fossil was discovered in Canada's Burgess shale, has been put to rights — and even given a place in a family tree. According to a new study of the creatures' odd claws, Hallucigenia sparsa is the ancestor of modern-day velvet worms, which are strange, sluglike creatures with centipede-style legs.

The finding is surprising because it rewrites the evolutionary history of spiders, insects and crustaceans, said study researcher Javier Ortega-Hernandez, a paleobiologist at the University of Cambridge. Most genetic studies have found that these arthropods are close relatives of today's velvet worms, Ortega-Hernandez said in a statement. But the new study finds that velvet worms are only distant cousins of arthropods. [See Images of Hallucigenia and Other Wacky Cambrian Creatures]

"The peculiar claws of Hallucigenia are a smoking gun that solves a long and heated debate in evolutionary biology," said study researcher Martin Smith, an earth scientist at the University of Cambridge.

Weird worm

Hallucigenia lived during the Cambrian Explosion, a time when animal life exploded in diversity. The worms were seafloor dwellers and grew to be only about 1.3 inches (35 millimeters) long.

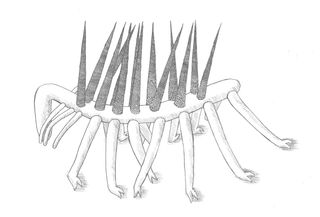

The ancient creature gets its name from the word "hallucination," a moniker the worm earned due to its weird body. The animal's head looks almost like its tail, and the creature has seven or eight pairs of legs as well as strange back-spikes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1992, Lars Ramskold, then at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, turned the animal right-side up. Even so the animal still puzzled scientists.

"Even with the correct orientation, Hallucigenia has been regarded as problematic, because there are few features that connect it directly with living organisms," Ortega-Hernandez told Live Science in an email.

It was Hallucigenia's claws that gave the crucial clue to the worm's family relationships. The claws are made of a fingernail-like substance stacked like cups (or like Russian dolls), the same structure found in the modified chewing claws of modern velvet worms.

"This is very significant, because the only other occurrence of that configuration is found in velvet worms (also known as onychophorans)," Ortega-Hernandez wrote.

The finding, detailed online yesterday (Aug. 17) in the journal Nature, puts Hallucigenia in the lineage of velvet worms, but disrupts the link between those worms and modern spiders, insects and crustaceans, a group known as arthropods. In fact, Ortega-Hernandez said, the new results suggest that arthropods are more closely related to another weird organism: the water bear, or tardigrade. These microscopic cuties are incredibly hardy. They can even survive the vacuum of space.

"It’s often thought that modern animal groups arose fully formed during the Cambrian Explosion," Smith said. "But evolution is a gradual process: Today’s complex anatomies emerged step by step, one feature at a time. By deciphering 'in-between' fossils like Hallucigenia, we can determine how different animal groups built up their modern body plans."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.