Oil Drilling Contaminated Western Amazon Rainforest, Study Confirms

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Peru's Amazon rainforest is extensively contaminated from decades of oil and gas drilling, researchers reported yesterday (June 12) here at the annual Goldschmidt geochemistry conference.

In the past decade, volatile demonstrations by indigenous groups and tangled lawsuits against oil companies have exposed the toxic legacy of decades of oil drilling in the Western Amazon. People living in the rainforest say they are suffering health effects from the nearby polluted drilling and waste sites, and from eating plants and wildlife laced with heavy metals and petroleum compounds.

But lax government regulations during the early years of oil exploration, combined with a lack of environmental monitoring, mean there's little data on the true extent of contamination in the richly diverse rainforest.

"I was surprised by how little has been published," said study co-author Antoni Rosell-Melé, an environmental chemist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona in Spain.

Now, using publicly available water sampling data, Rosell-Melé and his colleagues have built a comprehensive database of contamination levels during the past 30 years in Peru's remote rainforest. The team plans to publish the database so other scientists can use the data to better understand how oil exploration affects the Amazon rainforest. [See Stunning Photos of the Amazon Rainforest]

"We know a lot about the impacts of deforestation, but very little has been published about the impacts of oil exploration," Rosell-Melé said.

The results confirm the complaints from indigenous and green groups: Pollutant levels exceed government and international standards, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When we extract oil, it has a very high price for the environment, and sometimes, it's not paid by those who use the oil," Rosell-Melé said.

The data comes from Peruvian public agencies, oil companies and non-governmental organizations, but has never been collected in one place. The database contains 4,480 samples from 10 major rivers, taken between 1983 and 2013.

Nearly 70 percent of the river water samples exceed Peru's limits for lead, and 20 percent exceed cadmium limits, Rosell-Melé said. "There's clearly been impacts from discharge into the rivers," he said.

During the early decades of oil mining, companies dumped their drilling waste into open pits or directly into rivers and streams. Leaky pipelines and wells, as well as accidental oil spills could also produce the contamination detected in the water samples. The heavy metals and other compounds tested were at higher levels downstream of the discharge sites, as compared with levels upstream, which suggests the oil discharges had caused the contamination, the researchers said.

Health effects

High levels of lead and cadmium have been found in blood taken from indigenous people living in the rainforest, and from the wildlife these groups hunt for food, according to earlier studies.

Activists believe the contamination results from such pollutants moving up the food chain, from wildlife to indigenous peoples who rely on the rainforest ecosystem for a subsistence lifestyle.

To confirm that rainforest animals eat in oil-contaminated areas, the researchers set up camera traps in the forest. The traps caught animals such as tapirs feeding directly on the chemicals from the spills, and researchers documented oil in the animals' feces. Rosell-Melé thinks the animals are attracted to the taste of salty wastewater and chemicals. Soils in the rainforest are low in salt, and animals may mistake the spills for natural salt licks, Rossell-Mele said.

According to the database, pollution levels in Peru's rainforest rivers started to drop after 2007, when the government ordered drilling companies to stop dumping toxic waste into rivers.

"The situation has improved over what it used to be, but it's not acceptable by Western standards," Rosell-Melé said.

The new environmental regulations haven't completely prevented new toxic waste spills, however. Peru's Environment Ministry declared an environmental emergency in the Corrientes and Pastaza River basins in March 2013 due to drilling contamination. [Photos: The 10 Most Pristine Places on Earth]

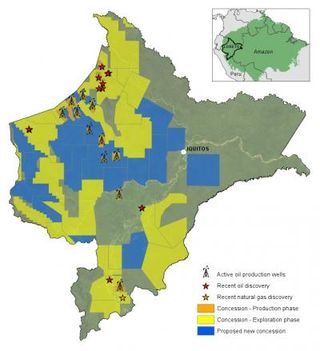

About 30 percent of the world's rainforests overlie fossil fuel reservoirs, Rosell-Melé said. Huge oil and gas reserves have been discovered under the Amazon rainforest in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and western Brazil. Oil drilling in the Western Amazon peaked in the 1970s, with exploration funded by both private companies and national governments. The rise in oil prices during the 2000s sparked a new drilling boom in the area. More than 180 areas zoned for new exploration and development now cover a section of Amazon rainforest the size of Germany.

"The exploitation of these resources is a threat to biological and cultural diversity," Rosell-Melé said.

EmailBecky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular