Why Is Africa Ripping Apart? Seismic Scan May Tell

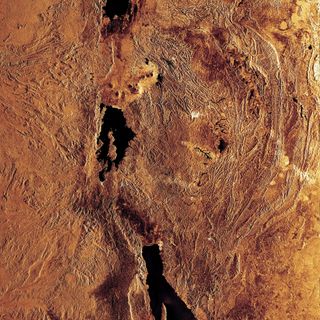

Arrays of sensors stretching across more than 1,500 miles in Africa are now probing the giant crack in the Earth located there — a fissure linked with human evolution — to discover why and how continents get ripped apart.

Over the course of millions of years, Earth's continents break up as they are slowly torn apart by the planet's tectonic forces. All the ocean basins on the Earth started as continental rifts, such as the Rio Grande rift in North America and Asia's Baikal rift in Siberia.

The giant rift in Eastern Africa was born when Arabia and Africa began pulling away from each other about 26 million to 29 million years ago. Although this rift has grown less than 1 inch (2.54 centimeters) per year, the dramatic results include the formation and ongoing spread of the Red Sea, as well as the East African Rift Valley, the landscape that might have been home to the first humans.

"Yet, in spite of numerous geophysical and geological studies, we still do not know much about the processes that tear open continents and form continental rifts," said researcher Stephen Gao, a seismologist at the Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla, Mo. This is partly because such research has mostly focused on mature segments of these chasms, as opposed to ones that are still in development, he explained. [Earth Quiz: Mysteries of the Blue Marble]

Seismic SAFARI

Geodynamic models suggest that below mature rifts, a region called the asthenosphere is upwelling. The asthenosphere is the hotter, weaker, upper part of the mantle that lies below the lithosphere, the planet's outer, rigid shell. So far, there are two contenders for what might cause this upwelling: anomalies deeper in the mantle or thinning of the lithosphere due to distant stresses.

To help find out which of the two different rifting models is correct, the Seismic Arrays for African Rift Initiation (SAFARI) project installed 50 seismic stations across Africa in the summer of 2012, each spaced about 17 to 50 miles (28 to 80 kilometers) apart.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"One of the techniques that we will use to image the Earth beneath the SAFARI stations is called seismic tomography, which is in principle similar to the X-ray CAT-scan technique used in hospitals," Gao told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet. "The only differences are that our sources of the 'rays' are earthquakes and man-made explosions, and the receivers are the seismic stations such as the 50 SAFARI stations."

Altogether, these arrays encompass a length of about 1,550 miles (2,500 km) and are located in four countries — Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia.

"I think the project has a positive impact on local communities," Gao said. "Some of our 50 SAFARI seismic stations are on local schools, and the teachers and students were excited and were proud about the fact that their school was selected for a high-tech scientific instrument. We believe that this project showed some kids that the outside world is different and even fascinating."

The arrays will image the areas under the Okavango, Luangwa and Malawi rifts, the southwest and southernmost segments of the East African Rift system. These so-called incipient rifts are not yet mature and could thus shed light on why and how rifting occurs.

"This is the first large-scale project to image the structure and deformation beneath an incipient rift," Gao said. "The Okavango rift in Botswana is as young as a few tens-of-thousand years, while most other rifts such as the Rio Grande and Baikal rifts are as old as 35 million years."

Upwelling or thinning?

If thermal or dynamic anomalies deep in the mantle are responsible for rifting, then upwelling from the asthenosphere should already be occurring beneath these incipient rifts. In contrast, if thinning of the lithosphere is the cause of rifting, then any levels of upwelling should be insignificant because the lithosphere should not have thinned adequately for major upwelling to occur yet.

A magnitude-5.6 earthquake in November near the northern end of the Indian Ocean's mid-ocean ridge sent out seismic waves that were more than 1 second slower than predicted. This supports the idea that the mantle layer beneath Southern Africa is hotter than normal, perhaps due to a jet of magma known as a mantle plume that geologists have proposed exists beneath this area.

To image the structures beneath these rifts and pin down what the rifting mechanism in Eastern Africa is, researchers need data from more than just one event. The seismic arrays will be deployed for 24 months, and each station will sample the Earth for seismic waves 50 times per second.

"We are anxious to see if there are melted rocks in the mantle beneath the rifts, if there is convective mantle flow that is driving the rifting process, and how much the crust has been thinned in different portions of the rifts," Gao said. "But this cannot be done until next summer, when all the data recorded by SAFARI are processed."

The scientists detailed their findings to date in the June 11 issue of Eos, the online newspaper of the American Geophysical Union.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Most Popular