AIDS Exhibit Explores Early Years of Epidemic

NEW YORK - Young people today do not know a world without AIDS, and many may not be aware of the confusion, fear and panic that surrounded its emergence as a completely new disease.

And even though it was just over 30 years ago, some people not directly affected by the epidemic may have forgotten this tumultuous time.

A new exhibit at the New York Historical Society uses artifacts — including clinicians notes, diary entries, audio and video clips, public health posters and newspaper articles — to retell the story of the early years of the AIDS epidemic.

Called AIDS in New York: The First Five Years, the exhibit focuses on the impact of the disease in New York City, one of the areas hardest hit by the epidemic. By the end of 1985, more than 3,700 New Yorkers had died of AIDS.

The exhibit covers the years 1981 through 1985. It weaves together the tale of scientific discovery around AIDS, with that of the hardships faced by patients, and the social and political clashes that held captive the nation's attention.

It includes a copy of the first medical journal article that mentioned AIDS, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, published June 5, 1981. In the exhibit, interviews with doctors highlight the mysteries surrounding the sudden emergence of rare diseases, such as Kaposi's sarcoma and pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, in populations of gay men — diseases that typically don't harm healthy people.

"We tried a few drugs but nothing changed. You don't lose a 33-year old patient. We were agonized," reads one quote from Dr. Donna Mildvan, who treated some of the first AIDS patients.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A transcript of a 1982 conference describes the moment when the disease was renamed from GRID, Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, to AIDS, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.

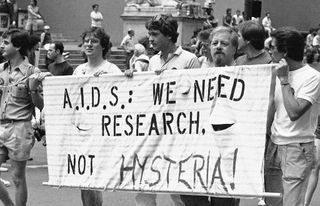

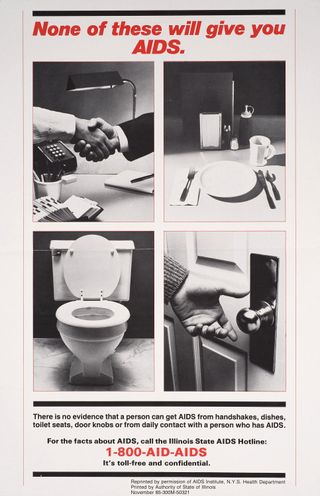

The exhibit also highlights the wealth of misconceptions about the disease in the early years. Even when researchers were fairly sure the disease was spread through the blood, and not through causal contact, some health care workers were hesitant to touch AIDS patients, and members of the public feared they might get the disease by riding the subway or dining out. In 1983, New York State funeral homes stopped embalming AIDS victims for a two-month period.

The start of the AIDS epidemic increased the stigma against gay and transgender people, which is described in the exhibit through depictions of anti-gay protests and media reports of violence against gays.

The final part of the exhibit describes the discovery of the AIDS virus, which would become known as human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, in 1983, as well as the start of AIDS activism, including the formation of the group ACT UP, which aimed to bring an end to the silence surrounding the AIDS epidemic and draw attention to the need for research about the disease.

"For those who lost partners, children, siblings, parents, and friends, the memory of the fear and mystery that pervaded New York at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic remains vivid," Jean Ashton, curator of the exhibit, said in a statement.

"For many people today, though, these years are now a little-understood and nearly forgotten historical period. Yet the trajectory of HIV/AIDS changed paradigms in medicine, society, politics and culture in ways that are still being felt," Ashton said.

The exhibit is on view at the New York Historical Society from June 7 through Sept. 15.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily @MyHealth_MHND, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on LiveScience.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.