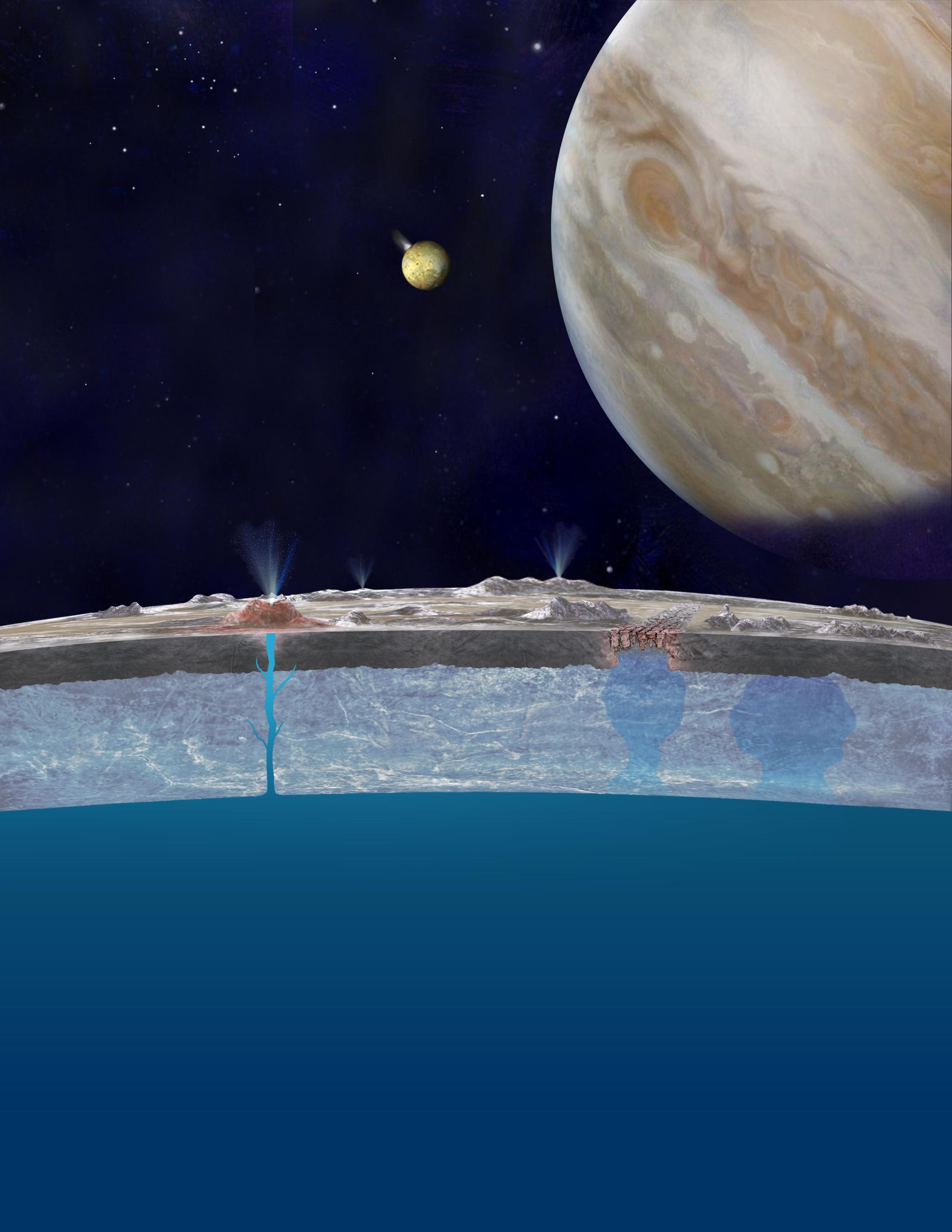

The huge ocean sloshing beneath the icy shell of Jupiter's moon Europa likely makes its way to the surface in some places, suggesting astronomers may not need to drill down deep to investigate it, a new study reports.

Scientists have detected chemicals on Europa's frozen surface that could only come from the global liquid-water ocean beneath, implying the two are in contact and potentially opening a window into an environment that may be capable of supporting life as we know it.

"We now have evidence that Europa's ocean is not isolated — that the ocean and the surface talk to each other and exchange chemicals," study lead author Mike Brown, of Caltech in Pasadena, said in a statement.

"That means that energy might be going into the ocean, which is important in terms of the possibilities for life there," Brown added. "It also means that if you’d like to know what’s in the ocean, you can just go to the surface and scrape some off." [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

Studying Europa's icy shell

Brown and co-author Kevin Hand, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, scrutinized Europa's surface with Hawaii's powerful Keck II Telescope, which sports an adaptive-optics system to compensate for the blurring caused by Earth's atmosphere.

Europa is tidally locked with Jupiter, meaning one hemisphere of the moon always leads in its orbit while the other one always trails. Keck detected a mysterious signal on Europa's trailing side that no other instrument had seen before, researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

“We now have the best spectrum of this thing in the world,” Brown said. “Nobody knew there was this little dip in the spectrum because no one had the resolution to zoom in on it before.”

After much experimentation in the lab, Brown and Hand determined that the spectroscopic signal was caused by a magnesium sulfate salt called epsomite.

"Magnesium should not be on the surface of Europa unless it’s coming from the ocean," Brown said. "So that means ocean water gets onto the surface, and stuff on the surface presumably gets into the ocean water."

An Earth-like ocean?

But the astronomers don't think Europa's ocean, which is believed to be about 62 miles (100 kilometers) deep, is rich in magnesium sulfate.

That's because the epsomite signal comes only from Europa's trailing side, which is blasted with sulfur expelled by Jupiter's volcanic moon Io. If magnesium sulfate were bubbling up to the surface directly from the ocean, its signal should have been seen on the leading side, too, the reasoning goes.

Europa's ocean, Brown and Hand say, can be only one of two types — sulfate-rich or chlorine-rich. With sulfate-rich off the table, the oceanic magnesium source is likely magnesium chloride (which gets broken apart on the surface by radiation, leading to the formation of magnesium sulfate on the moon's trailing side after exposure to sulfur from Io).

Other chloride salts are probably in the water as well, such as sodium chloride and potassium chloride, the scientists added. Indeed, previous work by Brown showed that atomic sodium and potassium are present in Europa's wispy atmosphere.

The composition of Europa's ocean may thus be similar to that of Earth's seas, researchers said.

“If you could go swim down in the ocean of Europa and taste it, it would just taste like normal old salt," Brown said.

If that's the case, the 1,940-mile-wide (3,120 km) Europa would become even more intriguing to scientists searching for signs of life beyond our planet.

"If we’ve learned anything about life on Earth, it’s that where there’s liquid water, there’s generally life," Hand said. "And of course our ocean is a nice salty ocean. Perhaps Europa’s salty ocean is also a wonderful place for life."

The new study has been accepted for publication in the Astronomical Journal.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to Live Science. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. This article was first published on SPACE.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus