In Photos: A Tale of Two Censors

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two Censors

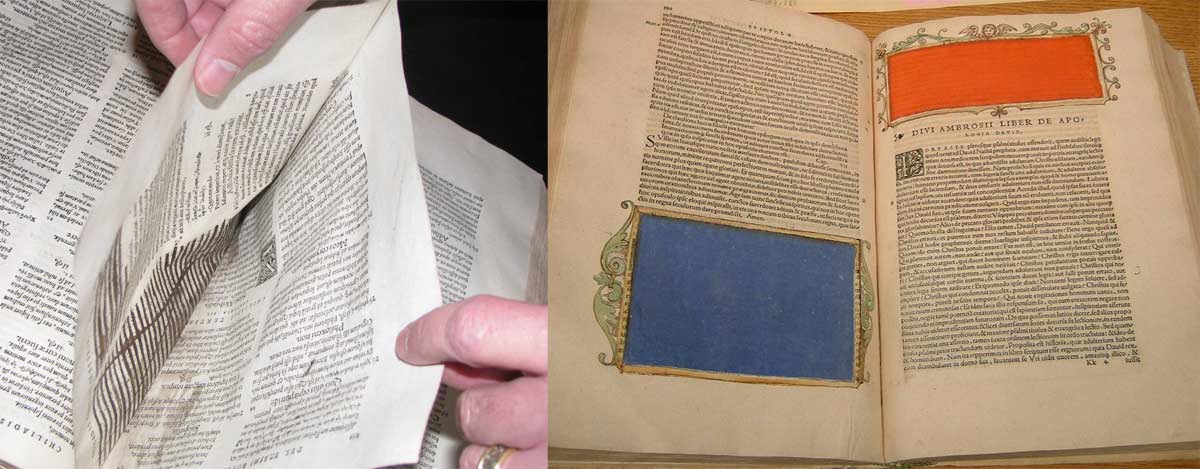

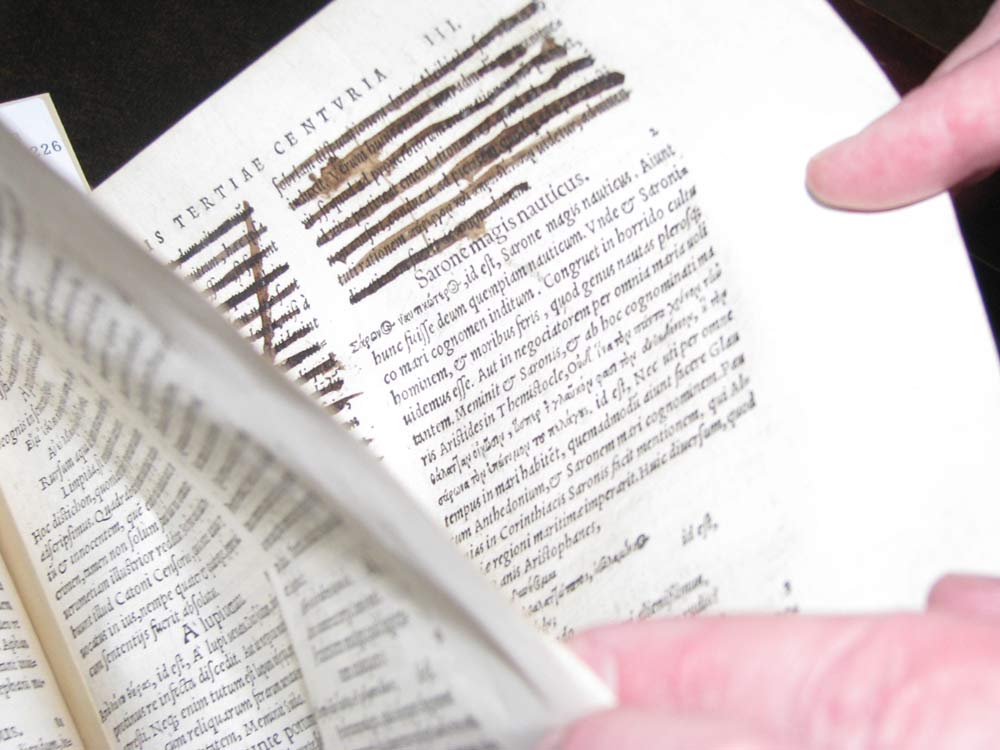

A newly catalogued 1541 book, written by Erasmus (left) has pages ripped out, text blotted out with ink and two pages glued together. This book is now in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto. A 1538 book in which Erasmus introduces the writings of fourth-century Saint Ambrose. In it Erasmus' work is censored but this time with great beauty, with watercolors and baroque frames; it is now at the Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies, also at the University of Toronto.

Erasmus of Rotterdam

Erasmus was born in Rotterdam sometime around 1466. He was a prolific writer who was critical of corruption in the Catholic Church. His lifetime would see a schism emerge in Western Christianity that would see breakaway groups called Protestants fighting against Catholics. Erasmus was seen as being sympathetic to the Protestants and, in 1559, more than two decades after his death, his works were put on an index of forbidden books and subject to censorship.

It's Stuck

After four centuries the pages of the 1541 text are still stuck together. Librarian Pearce Carefoote (holding the pages) has curated an exhibition on censorship and written a book on the subject. He told LiveScience that he has never seen a case in which a censor used glue in his work. More research needs to be done to see what the glued together portion contained.

Praise of Folly

If that wasn't enough the censor appears to have written a note on the front in Latin. It reads (in translation) "O Erasmus, you were the first to write the praise of folly, indicating the foolishness of your own nature." One of Erasmus' works was called "The Praise of Folly." Carefoote says that we cannot be sure that this note was left by the censor, though the ink appears to match.

Careful Censoring

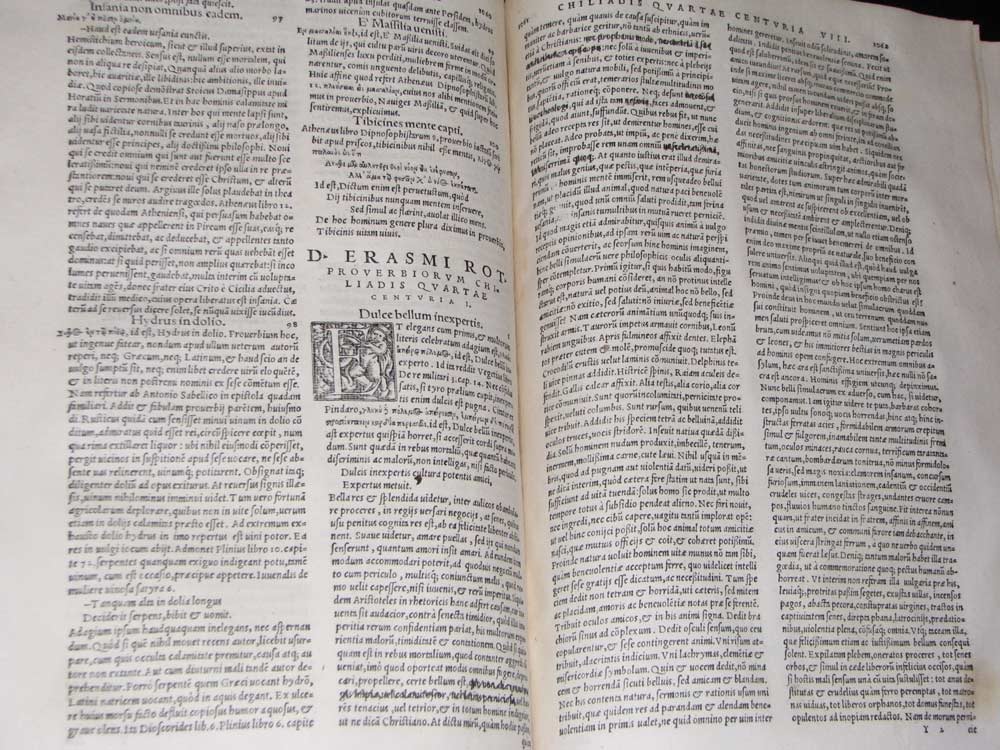

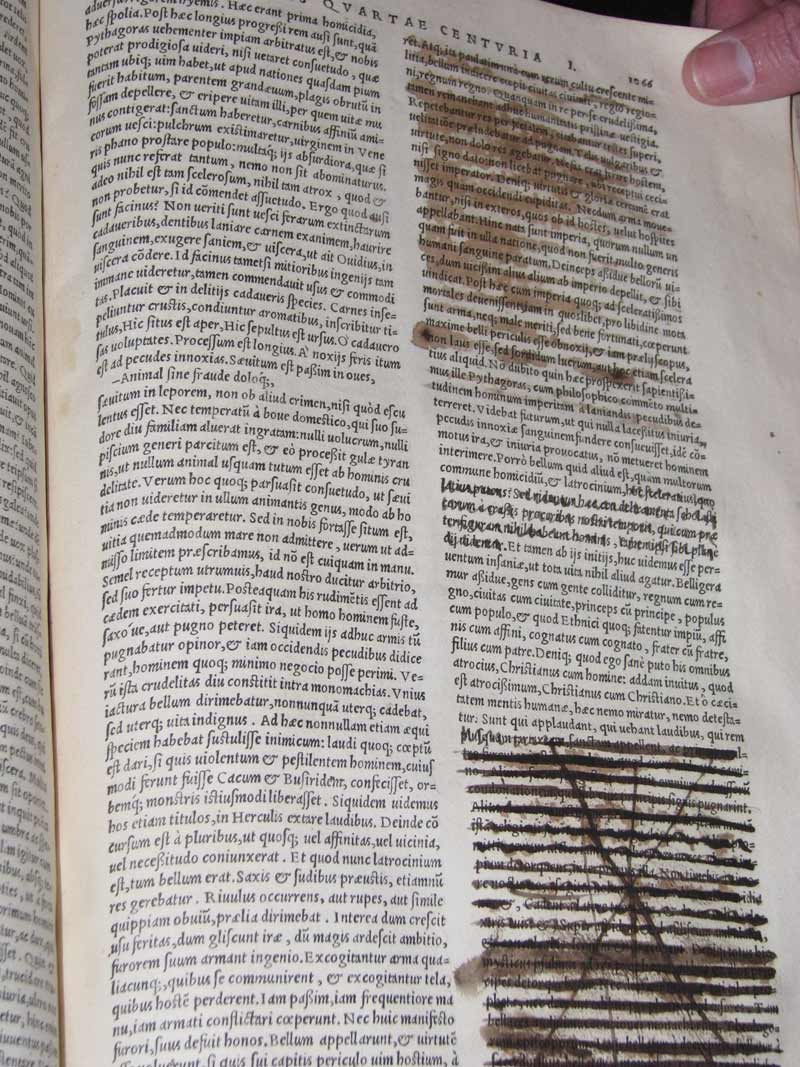

One section of the book starts with the phrase Dulce bellum inexpertis – “war is sweet to those who haven't experienced it.” At first it was subjected to some light censoring, just a sentence here and there ...

Lots of Marks

But, as the passage goes on, the censor goes to town, blanking out entire sections. More research needs to be done however Carefoote believes that the censor didn't like Erasmus's position against the idea of "just war."

Beauty in Censors

In contrast this 1538 book, containing essays by Erasmus introducing the work of St. Ambrose, was censored beautifully, this section with a blue pigment and ornately designed border.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Young Boy

This section, featuring an orange-colored pigment, has an image of at top, believed to be that of a putto, a male child.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus