The Truth about Tooth Decay

Are you worried that your mass consumption of Halloween candy this year will rot your teeth so badly that you will have the smile of a hockey player by next year?

Well, don't take this as an invitation to eat a dozen Zagnut bars in one sitting, but there are worse foods than candy to cause tooth decay. If you're the kind who never brushes your teeth, then you'd be better off avoiding potato chips and raisins.

The reason is that sugar doesn't rot your teeth. Surprised to hear that? Tooth decay is caused by acid-producing bacteria in your mouth that feast on carbohydrates, be it sugar from candy or starch from wholesome foods such as bread.

Potato chips and raisins cling to your teeth, giving the bacteria something to savor. But a simple chocolate bar can get washed away naturally with saliva. The faster a food is removed, the less chance it will have to feed bacteria and cause decay.

The oldest profession, dentistry

Tooth decay existed long before the dawn of M&M's. Archaeologists regularly find signs of tooth decay (and painful tooth repair ) as far back as the Neolithic period, about 9,000 BCE, when humans began to shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture and grain-eating. Starches in the grain and other plants led to tooth decay. Before this, in the Atkins-diet era, tooth decay was rare.

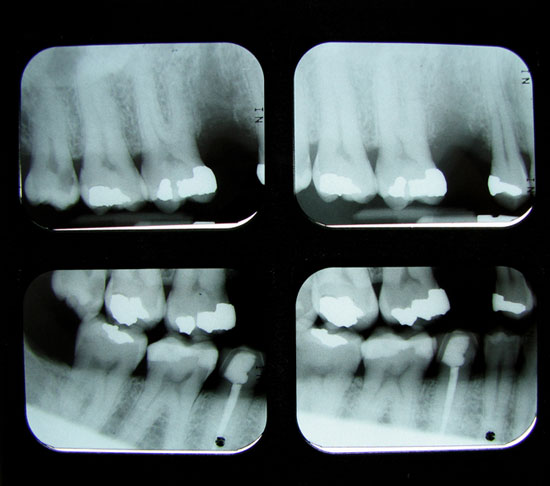

Several species of oral bacteria feed on carbohydrates and produce acid as a byproduct through a process of simple fermentation. These bacteria live on the teeth in a biofilm called plaque. The acid slowly eats away at the tooth enamel, a thin layer of largely calcium that covers the tooth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The human tooth is in a constant state of mineralization and demineralization. Saliva helps neutralize acid from food to keep demineralization at a minimum. But if the region gets too acidic, then demineralization takes over and rot sets in.

Flavor savor

Brushing regularly will clear away food residue and starve the bacteria, keeping its growth in check. In the absence of brushing, the carbohydrates that linger the longest can cause the most damage.

Harald Linke of the New York University Dental Center has conducted numerous studies on the staying power of food on teeth. He has found that cooked starches, particularly potato starch in products such as potato chips, cling longer to the teeth than many sugar foods, like chocolate bars, thus leading to a longer period of acid production.

Other studies have found that tooth decay is related more to the frequency of eating than to the amount of starch or sugar. The best scenario for the teeth is to eat three meals a day (and, of course, to brush). Saliva naturally washes away residual food during the period between meals. Frequent snacking hurts the teeth because it reintroduces food particles and keeps a thin layer on the teeth all day, enabling plaque buildup.

That is, you can eat a reasonable amount of sweets and not get cavities if you eat the sweets with regular meals and then brush.

Acid-aide

Soda pop has long been associated with tooth decay because it is loaded with sticky sugar, as high as 10 teaspoons per bottle, and is often drunk between meals. But some dentists are worried that soda pop and sports drinks can cause tooth decay not just because of the sugar but because of the acid content, too. The word on the street, for example, is that an iron nail will dissolve in Pepsi in a couple of days.

That sounds frightening for the teeth, but no one is holding Pepsi in his mouth for two days. If the acid doesn't stick to the tooth or lower the pH of the mouth, then it cannot cause any damage. While acid baths in the form of constant soda sipping might take their toll, no health study has conclusively demonstrated a link between tooth decay and acidic drinks.

My only worry is my acidic tongue.

- 10 Easy Paths to Self Destruction

- Top 10 Bad Things That Are Good For You

- Why Do We Grind Our Teeth?

Christopher Wanjek is the author of the books “Bad Medicine” and “Food At Work.” Got a question about Bad Medicine? Email Wanjek. If it’s really bad, he just might answer it in a future column. Bad Medicine appears each Tuesday on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus