Fatty Ears May Help Baleen Whales Hear

The remains of stranded minke whales, mostly from Massachusetts beaches, have helped scientists understand how they and their close relatives hear.

Minke whales are baleen whales, whales that use baleen plates in their mouths to filter meals of tiny organisms out of the ocean. Scientists have known for some time that their relatives, the toothed whales including killer whales, sperm whales and dolphins, use fat associated with their lower jaws to guide sound into their ears. Land animals use air-filled ear canals to do the same thing.

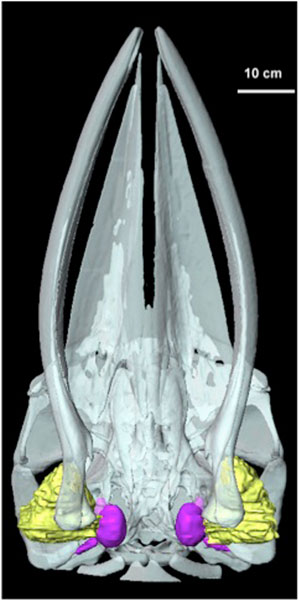

Using a combination of scans and dissection, a team of researchers found the baleen whales have similar lobes of fat that appear to provide a direct conduit for sound to the middle and inner ear.

Baleen whales' hearing systems have been harder to study than those of toothed whales. Their size is part of the problem, as baleen whales include the largest animal ever to have lived, the blue whale. The animals' large size makes them difficult to dissect or fit into a scanner. What's more, their bodies are hard to come by; live baleen whales are not kept in captivity and decompose rapidly in the rare event that they die on a beach.

Minke whales, meanwhile, are relatively small and abundant.

Lead researcher Maya Yamato, an oceanography graduate student in a joint MIT/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution program, received the heads of seven minkes that had stranded and died. Using computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and verifying the results through dissections, she and colleagues identified the fat lobes associated with the lower jaws in these baleen whales.

This is the first study to describe the fat beside the ears as a potential sound reception pathway for baleen whales, Yamato and colleagues write in a study published online April 10 in the journal The Anatomical Record.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Although we propose the ear fats to be a primary sound reception pathway in the minke whale, it is also possible that additional mechanisms of sound reception may exist in baleen whales," they write.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.