Fossil Microbes Could be Earth's Oldest Life

Even before there was much oxygen on Earth, there was life, a new fossil discovery reveals.

The findings have implications for finding alien life in our solar system such as on Mars, the researchers speculate.

Scientists have unearthed microscopic fossils of microbes that subsisted on sulfur instead of oxygen almost 3.5 billion years ago. At the time, the Earth was a warm, violent place without land plants or algae to produce oxygen through photosynthesis. The sky was overcast, trapping heat near Earth's surface, and the oceans were the temperature of a hot bath.

"At last, we have good solid evidence for life over 3.4 billion years ago," study researcher Martin Brasier of Oxford University said of the fossils, which were found in Australia. "It confirms there were bacteria at this time, living without oxygen."

Ancient life

Sulfur-loving bacteria still exist today, found in hydrothermal vents, hot springs, soil and other extreme environments that do not have much oxygen. The newly discovered fossils were found in some of the oldest sedimentary rocks on Earth, in a remote part of Western Australia called Strelley Pool.

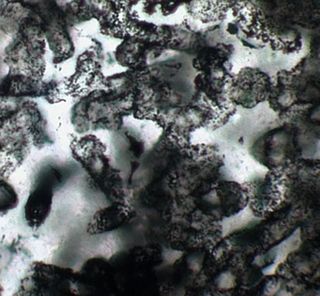

Determining that microscopic formations that look like fossils are actually biological in origin isn't easy. Brasier and his colleagues say their discovery satisfies three crucial tests: First, the preservation is good, showing cell-like structures of similar size. The fossils have similarities to well-known but newer microfossils, and they are not oddly shaped.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Additionally, the researchers reported in Nature Geoscience on Aug. 21, the cells are clustered in groups, appear only in the habitats you'd expect to see such organisms, and are found attached to sand grains, all markers of biological behavior.

Finally, the chemical makeup of the fossils suggests biological metabolism, the researchers reported. Fool's gold, or pyrite, found around the microfossils is likely a byproduct of the organisms' sulfur metabolism, they wrote.

Old or oldest?

Previously, researchers have reported the existence of microfossils up to 3.5 billion years old, which would mean the new discovery isn't the oldest example of life on Earth. In 1993, J. William Schopf, a paleobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, reported finding these older fossils near the site of the new fossil find. Brasier and his team disagree that Schopf's discovery is a sign of life, arguing that the structures found are a byproduct of mineralization.

The debate and the new findings have implications for the search for extraterrestrial life in our solar system, providing a template for what such life might look like. (Similar hopes have been pinned on the controversial "arsenic bacteria" reported in the journal Science in 2010.)

"Could these sorts of things exist on Mars? It's just about conceivable," Brasier said. "But it would need these approaches — mapping the chemistry of any microfossils in fine detail and convincing three-dimensional images — to support any evidence for life on Mars."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.