Copying Someone's Behavior? Watch Who You Mimic

While imitating another may be a sincere form of flattery, such mirroring can get you into trouble socially if you're copying the wrong person, new research shows.

When participants in the study mirrored (or copied the mannerisms of) an unlikeable person, they were also judged as less competent and likeable by others, the researchers found.

Mirroring happens all the time and has been shown to involve mirror neurons, which are the cells in the brain that activate when we watch someone else perform a particular action that we also perform ourselves.

One common mirroring situation occurs when a person laughs. Scientists have found that the brain responds to the sound of laughter and preps the muscles in the face to also laugh or smile. Other examples of mimicking behaviors include crossing your arms after someone you're standing next to does so, or moving nearer to someone you're speaking to after they lean in closer.

"Mimicry is a crucial part of social intelligence," study researcher Piotr Winkielman, a professor of psychology at the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement. "But it is not enough to simply know how to mimic. It's also important to know when and when not to."

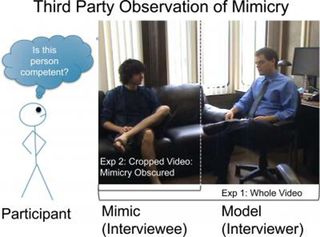

In the study, Winkielman and colleagues asked participants to watch several videos of staged interviews between two people. Some participants viewed videos in which the interviewer was friendly to the other person, and others saw videos in which that same interviewer was unfriendly.

The interviewees in the videos either mimicked or did not mimic the interviewer's simple mannerisms, including leg-crossing or chin-touching. Participants were not instructed to watch for mimicry and reported no awareness of it. After watching each video, participants evaluated the person interviewed in the video on general competence, likability and trustworthiness.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The participants rated the interviewees who mimicked the behavior of the unfriendly interviewer as less competent than those who didn't mirror him. This suggests that, in the eyes of the outside observers, imitating an undesirable model incurs reputational costs, according to the study, which will be published in a forthcoming issue of journal Psychological Science.

"The success of mirroring depends on mirroring the right people at the right time for the right reasons," Winkielman said. "Sometimes the socially intelligent thing to do is not to imitate."

In a corresponding experiment, participants watched the same videos but with the interviewer obscured. Because they couldn't see any evidence of mimicry, they did not judge the interviewees who mirrored the rude interviewer more harshly.

You can follow LiveScience writer Remy Melina on Twitter @remymelina. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Most Popular