Razor-thin crystalline film 'built atom-by-atom' gets electrons moving 7 times faster than in semiconductors

Scientists observed record-breaking electron mobility — seven times higher than in conventional semiconductors — with a material made from the same elements as quartz and gold.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have developed a new type of razor-thin crystal film semiconductor that enables electrons to move seven times faster than they do in traditional semiconductors — and it could have huge implications for electronic devices.

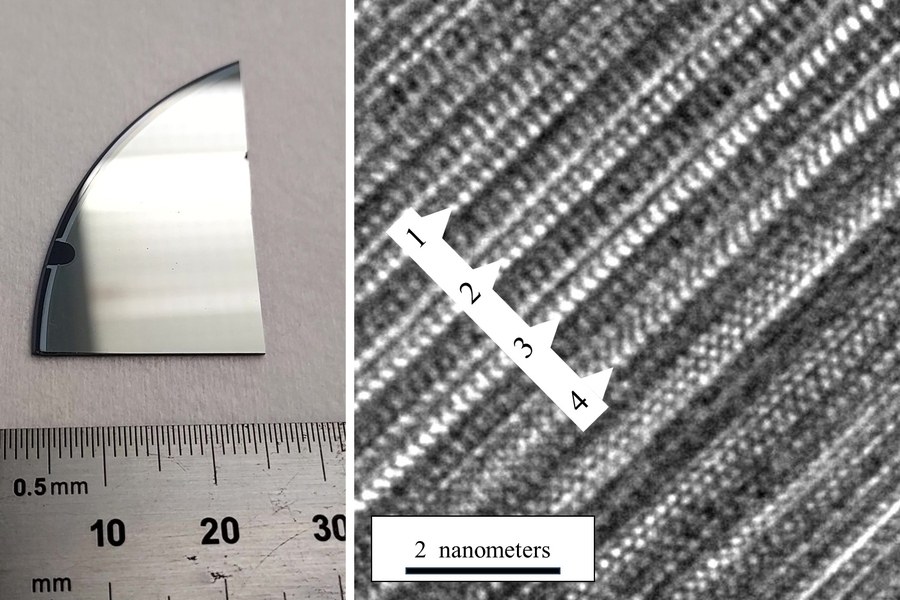

In a study published July 1 in the journal Materials Today Physics, physicists created an extremely thin film from a crystalline material called ternary tetradymite.

The film — measuring just 100 nanometers wide, or about one-thousandth of the thickness of a human hair — was created through a process called molecular beam epitaxy, which involves precisely controlling beams of molecules to build a material atom-by-atom. This process allows materials to be constructed with minimal flaws or defects, enabling greater electron mobility, a measure of how easily electrons move through a material under an electric field.

When the scientists applied an electric current to the film, they recorded electrons moving at record-breaking speeds of 10,000 centimeters squared per volt-second (cm^2/V-s). By comparison, electrons typically move at about 1,400 cm^2/V-s in standard silicon semiconductors, and considerably slower in traditional copper wiring.

Related: Charging future EVs could take seconds with new sodium-ion battery tech

This sky-high electron mobility translates to better conductivity. That, in turn, paves the way for more efficient and powerful electronic devices that emit less heat and waste less energy.

The researchers likened the film's properties to "a highway without traffic," saying that such materials "will be essential for more efficient and sustainable electronic devices that can do more work with less power." Potential applications include wearable thermoelectric devices that convert waste heat into electricity and "spintronic" devices, which use electron spin instead of charge to process information, the scientists said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Before, what people had achieved in terms of electron mobility in these systems was like traffic on a road under construction — you’re backed up, you can’t drive, it’s dusty, and it’s a mess," Jagadeesh Moodera, a physicist at MIT, said in a statement. "In this newly optimized material, it’s like driving on the Mass Pike with no traffic."

The scientists measured electron mobility in the material by placing the crystalline film in an extremely cold environment under a magnetic field. They then passed electrical current through it and measured quantum oscillations, which occur when electrical resistance fluctuates in response to a magnetic field.

Even tiny defects in the material can affect electronic mobility by obstructing the movement of electrons. As such, the scientists hope that refining the process for creating the film will produce even better results.

"This is showing it’s possible to go a giant step further, when properly controlling these complex systems," Moodera said. "This tells us we’re in the right direction, and we have the right system to proceed further, to keep perfecting this material down to even much thinner films and proximity coupling for use in future spintronics and wearable thermoelectric devices."

Owen Hughes is a freelance writer and editor specializing in data and digital technologies. Previously a senior editor at ZDNET, Owen has been writing about tech for more than a decade, during which time he has covered everything from AI, cybersecurity and supercomputers to programming languages and public sector IT. Owen is particularly interested in the intersection of technology, life and work – in his previous roles at ZDNET and TechRepublic, he wrote extensively about business leadership, digital transformation and the evolving dynamics of remote work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus