The Milky Way's supermassive black hole is spinning incredibly fast and at the wrong angle. Scientists may finally know why.

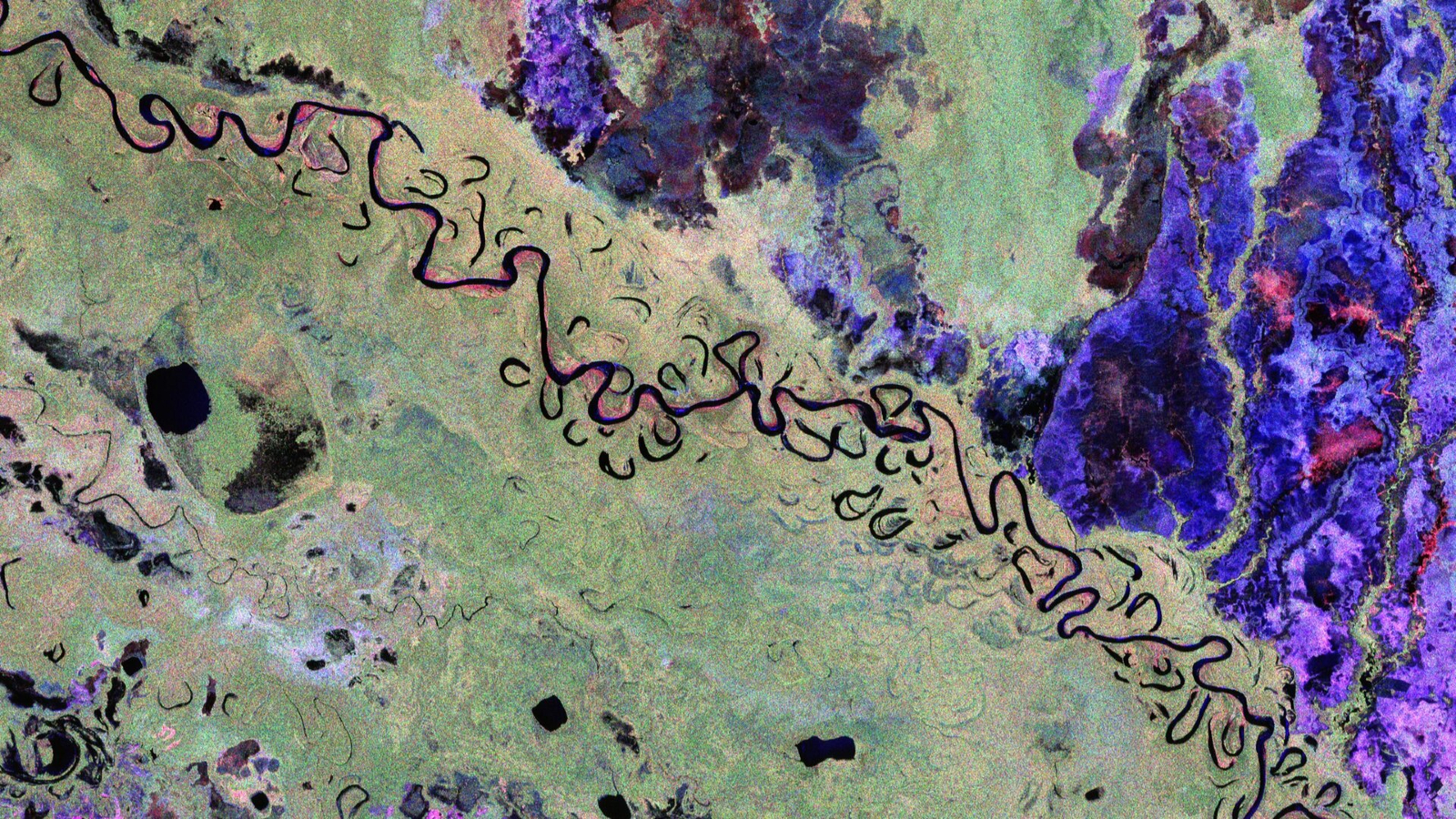

Observations from the Event Horizon Telescope may reveal a secret merger in our supermassive black hole's past, potentially explaining the cosmic monster's unusual spin.

Astronomers studying the Milky Way's supermassive black hole have found "compelling evidence" that could finally help explain its mysterious past.

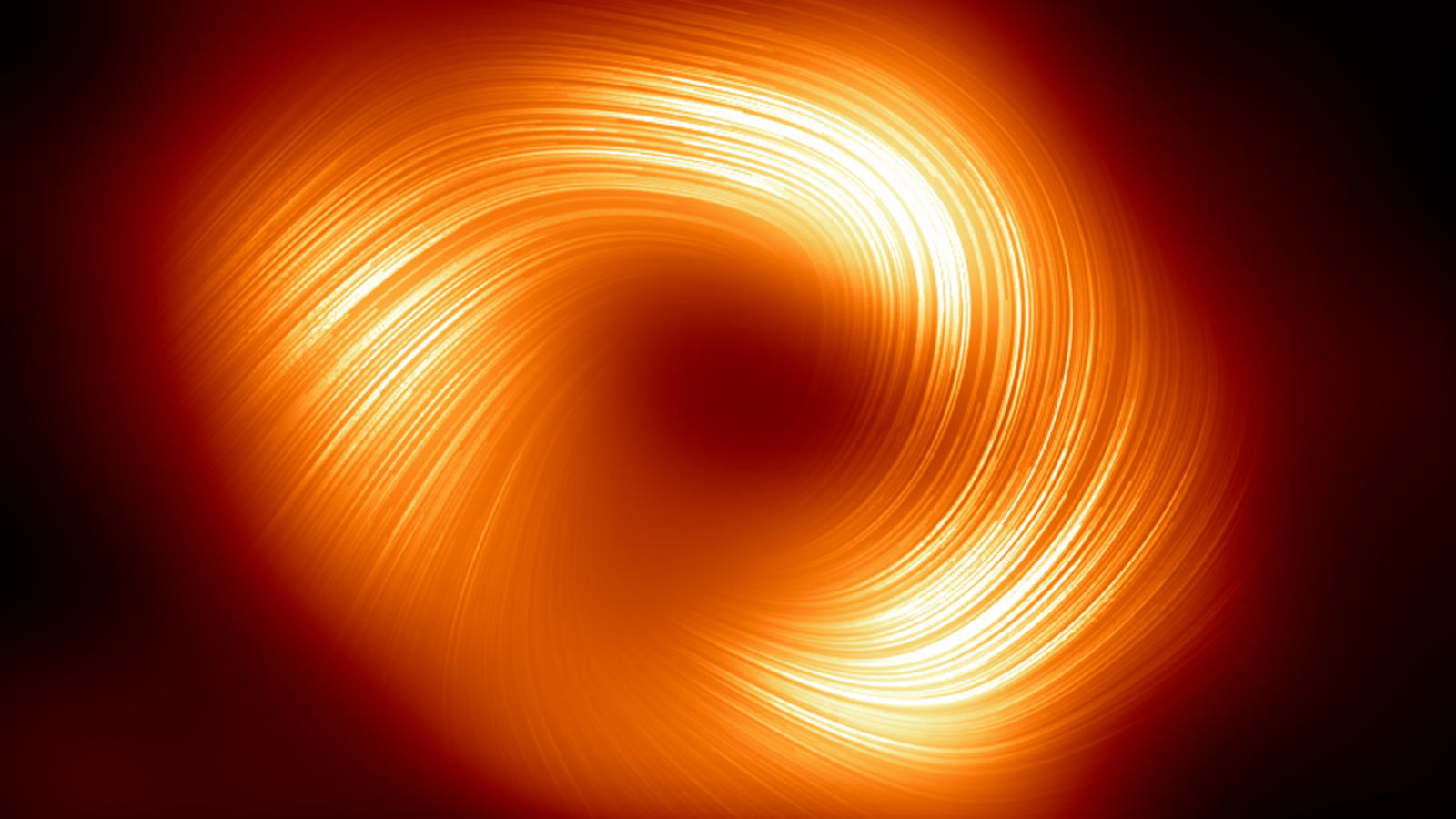

Located 26,000 light-years away in the center of our galaxy, Sagittarius A* is a gargantuan tear in space-time that is 4 million times the mass of our sun and 14.6 million miles (23.5 million kilometers) wide.

But how the black hole came to be, and why it is spinning surprisingly fast and out of orientation with the rest of the galaxy, remain unknown. Now, data from the telescope that first captured the black hole's image in 2022 has revealed a clue: The Sagittarius A* we see today was born from a cataclysmic merger with another giant black hole billions of years ago — and it's still showing the effects of this violent collision. The researchers published their findings Sept. 6 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"This discovery paves the way for our understanding of how supermassive black holes grow and evolve," study lead author Yihan Wang, an astrophysicist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), said in a statement. "The misaligned high spin of Sgr A* indicates that it may have merged with another black hole, dramatically altering its amplitude and orientation of spin."

Despite making up a scant 0.0003% of the Milky Way's mass, Sagittarius A* is a powerful engine that periodically sucks matter in before spitting it out at near-light-speeds, creating a feedback process that has shaped our galaxy since its beginnings.

Related: Some black holes have a 'heartbeat' — and astronomers may finally know why

Scientists think the gigantic black hole started out much like others, born from the collapse of a giant star or gas cloud before gorging on anything that came too close. After swelling to a monstrous size, black holes can even feed on other supermassive black holes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Supermassive black hole mergers occur when entire galaxies merge together. Bumps and kinks in the Milky Way's disk indicate it likely collided with at least a dozen galaxies during the past 12 billion years. But astronomers still aren't sure how important black hole mergers are when it comes to creating supermassive black holes, or whether these tears in space-time can grow to such mind-boggling proportions simply by consuming gas and dust.

To look for direct evidence of Sagittarius A*'s origins, the researchers behind the new study used data taken from the Event Horizon Telescope to create a model of the black hole's behavior throughout time. Across a number of simulations, the astronomers discovered that the black hole's unusual spin — which is completely misaligned with our galaxy's rotation — was best explained by a massive merger event with the supermassive black hole of another galaxy.

"This merger likely occurred around 9 billion years ago, following the Milky Way's merger with the Gaia-Enceladus galaxy," study co-author Bing Zhang, a professor of physics and astronomy at UNLV, said in the statement. This merger not only adds evidence to the idea that black holes can grow ever larger by gobbling up their own kind, but also "provides insights into the dynamic history of our galaxy," Zhang added.

To uncover further evidence of giant black holes merging across the universe, the researchers say they are waiting for the construction of space-based gravitational wave telescopes such as NASA's and the ESA's Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) project. Once LISA is lifted to space in 2035, it will detect the shock waves created in space-time when supermassive black holes collide.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus