Never-before-seen brain cells discovered in mice. They're called gorditas.

Researchers discovered two previously-unknown cell types in the brains of adult mice and named one of these cell types "gorditas," due to their plump, rounded appearance, The Scientist reported.

Both newfound cell types are called glia, meaning they are part of a class of non-neuronal cells found in the nervous system that help out neurons by supplying structural support, nutrients and insulation, among many other functions. The two glial cells sprung from a pool of stem cells — self-renewing cells that can differentiate into different cell types — that the research team activated in their experiments.

These stem cells usually remain fairly dormant in the adult mouse brain, but the team figured out how to switch them on, according to the new study, published June 10 in the journal Science.

Related: From dino brains to thought control — 10 fascinating brain findings

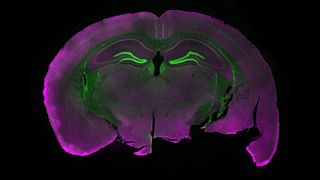

The stem cells sit in an area of the brain called the ventricular-subventricular zone (V-SVZ), within the walls of fluid-filled cavities called ventricles located on the left and right sides of the brain. By comparing dormant V-SVZ stem cells with active ones, the team found that most of the dormant cells carried high levels of a receptor called platelet-derived growth factor beta (PDGFR-beta), while only about half of the active cells carried a similar amount.

The team disabled PDGFR-beta in genetically modified mice; the GM mice without that receptor function had more active stem cells in the V-SVZ compared with unmodified mice. It was in these experiments that the gorditas cells appeared, as the newly-activated stem cells differentiated into new cell types.

The gorditas are a kind of glial cell known as an astrocyte, which are usually large and spiky-looking, unlike the chubby, squat gorditas. Astrocytes help to build, maintain and refine connections between neurons and also form part of the blood-brain barrier, which keeps harmful substances from entering the brain, according to BrainFacts.org, a public information initiative of the Society for Neuroscience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team also discovered a never-before-documented kind of oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC), an intermediate between stem cells and glial cells called oligodendrocytes, which insulate neurons in the brain and spinal cord, according to BrainFacts.org. OPCs usually lie buried deep within solid brain tissue, rather than within ventricle walls, as seen in the new study, study co-author Fiona Doetsch, a stem cell biologist and neuroscientist at the University of Basel in Switzerland, told The Scientist.

"Nobody expected them to be inside the ventricular system and attached to the wall of the ventricle, and so nobody had ever looked there before," Doetsch told The Scientist. "But when you actually look, you can see them really beautifully."

Although the OPCs didn't mature into full-blown oligodendrocytes, the cells still grabbed hold of neurons that reached into the V-SVZ via long-range "wires"; these connections may allow the cells to communicate with brain regions far away from the ventricles, Doetsch suggested, but the OPCs' exact function is not yet known.

The new study is "a very important addition to the whole story about these fascinating [stem] cells that exist in the adult brain of rodents that have the capacity to generate new cells," Arturo Alvarez-Buylla, a developmental neuroscientist at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the work, told The Scientist.

Read more about the newfound brain cells in The Scientist.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Most Popular