Ancient Roman necropolis holding more than 60 skeletons and luxury goods discovered in central Italy

A newfound necropolis in central Italy that once sat near an exclusive villa along an ancient road holds the remains of 67 people and their treasures, including gold jewelry.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A Roman-era necropolis that likely holds the remains of the upper crust has been discovered in central Italy, and it contains nearly 60 graves replete with gold jewelry and the remains of leather footwear, pottery and other precious goods.

The cemetery, found ahead of construction work for a solar energy project in the town of Tuscania, may have been associated with a hotel-like villa that served as a way station for important travelers, such as provincial officials.

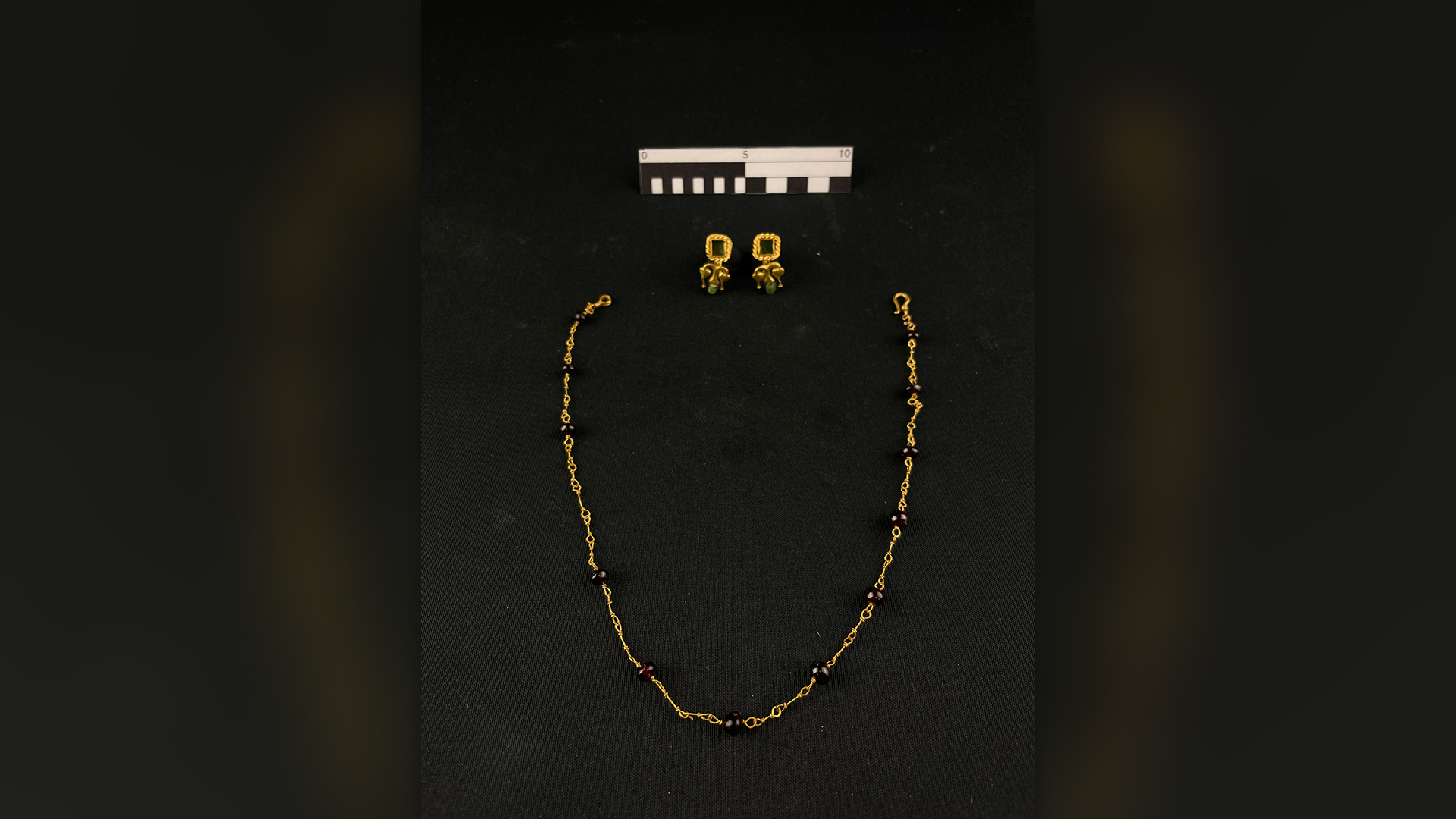

"The jewels, but also the glass, pottery, the footwear, the numerous coins, give us an image of people who enjoyed a certain well-being and could afford some small luxuries," Emanuele Giannini of the archaeology firm Eos Arc and the lead archaeologist at the site, told Live Science in an email.

Most of the tombs were in the so-called "cappuccina" style — a common burial type in which the deceased were covered with stone or ceramic tiles arranged in an A-frame shape. However, the archaeologists also found simple graves with no such covering, as well as skeletons contained in large ceramic vessels and evidence of some cremations.

Related: Elite Roman man buried with sword may have been 'restrained' in death

Dated to the height of the Roman Empire, to between the second and fourth centuries A.D., the necropolis was likely associated with a way station called a "mansio." There, dignitaries and other officials could stop for rest and refreshments while on government business. Giannini said that historical sources mention a mansio called Tabellaria along the via Aurelia, an ancient road which ran roughly from Pisa to Rome; the location of this mansio is just 1,640 feet (500 meters) from the cemetery, suggesting a connection.

So far, archaeologists have made only basic assessments of the newfound skeletons in terms of sex and age-at-death, and they suggest that the people lived in an urban context. "Discovering who they were is part of my research," Giannini said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

He and his team plan to undertake genetic studies to learn more about the 67 people who were buried in the necropolis, including trying to figure out whether the tombs that contained more than one person held the remains of family members.

In addition, the artifacts found in the excavation are being studied and restored, Giannini said, and when that is complete, they will be exhibited in a local museum. "We have already done a lot, but much still remains to be done," he said.

Using the latest technology, Giannini and his team hope to extend their research by reconstructing the lives of the ancient population of the area in as detailed a manner as possible. The project is "ambitious but realistic," according to Giannini, but key to better understanding how people lived during the time of the Roman Empire.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus