There Is Evidence That a Planet in Our Solar System Was Destroyed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An asteroid that slammed into the Sudan desert on Oct. 7, 2008, shot out lots of little space rocks holding a precious secret: diamonds that likely formed billions of years ago inside the embryo of a now-decimated planet.

That lost planet was the size of Mercury or perhaps Mars, researchers now say.

In the space rocks, which are also called meteorites, researchers found compounds common to diamonds on Earth, such as chromite, phosphate and iron-nickel sulfides. It's the first time these diamond components have been found in an extraterrestrial body, the researchers said in a new study describing the findings. [See Photos of Meteorites Discovered Around the World]

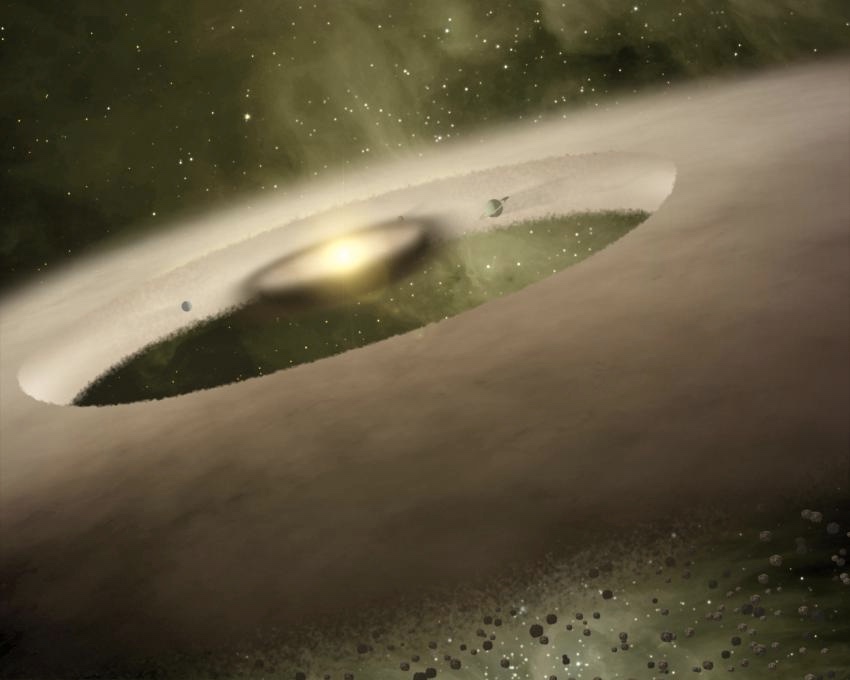

The finding provides more information on the early days of our solar system about 4.4 billion years ago, when the zone near the sun had several planetary embryos. Many of them coalesced into the planets we see today. Others fell into the sun or were ejected into interstellar space.

The meteorites were formed after an asteroid slammed into Earth's atmosphere — making it technically a meteor — exploding 23 miles (37 kilometers) above the Nubian Desert in Sudan. The explosion from the 13-foot-wide (4 meters) body shot fragments all over the desert below. Researchers picked up 50 of these pieces, which ranged in size from 0.4 to 4 inches (1 to 10 centimeters).

(An asteroid is a space rock, a meteor is a space rock burning up in Earth's atmosphere, and a meteorite is the leftover fragment that reaches Earth after a meteor comes through the atmosphere.)

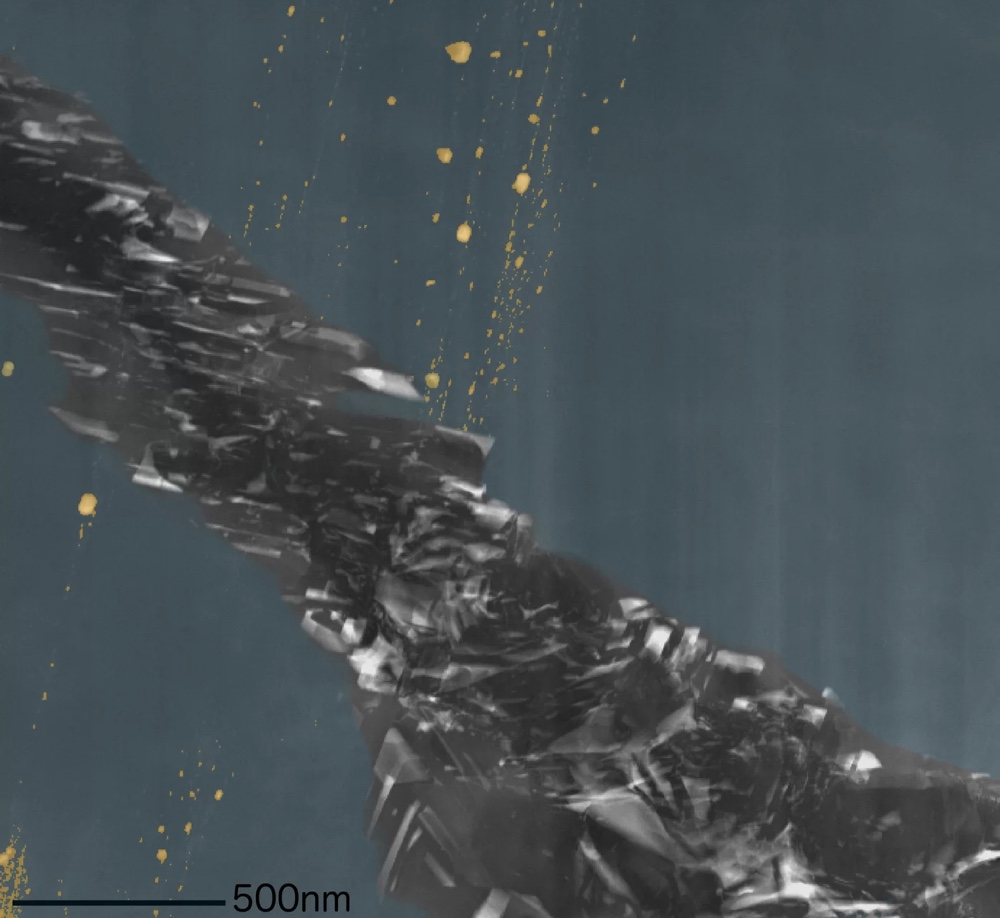

Researchers collected these tiny meteorites into a collection called "Almahata Sitta"; this is the Arabic word for "Station Six," a train station nearby the meteorite fall and between Wadi Halfa and Khartoum. After collecting the tiny meteorites, researchers discovered nano-size diamonds inside them. But at first, the origins of the diamonds eluded researchers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nanodiamonds can form from "normal" static pressure inside a large parent body like Earth, but there are other origin theories as well. High-energy collisions between worlds in space can leave such diamonds behind, as can deposition by chemical vapor,according to a statement from the Federal Polytechnic School of Lausanne in Switzerland.

The new study, however, revealed that the diamonds in the meteorite could form only under pressures higher than 20 gigapascals. This is an extremely high form of pressure that humans can generate with certain explosives.

"This level of internal pressure can only be explained if the planetary parent body was a Mercury- to Mars-sized planetary 'embryo,' depending on the layer in which the diamonds were formed," the researchers said in a statement from the Federal Polytechnic School of Lausanne in Switzerland. Farhang Nabiei, a doctoral student at the institution, led the research.

That planetary embryo would have then been destroyed through violent collisions, the researchers noted.

The research was published online yesterday (April 17) in the journal Nature Communications.

Originally published on Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus