Capturing Cacti Before They Disappear: Q&A with Cacti Curator John Trager

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Zina Deretsky is a board-certified medical illustrator and science-technology illustrator based in Oakland, California. She has done work for U.S. National Institutes of Health, U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. National Atmospheric and Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Her illustrations have been published in Science, Nature, National Geographic, the BBC and many other publications and websites. Her work can be seen at www.zina-studio.com. Deretsky contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Each human is attached to his or her environment in more ways than one. We are animals and we fit into a broader world of our local geology, meteorology, topography, plants and other organisms. In California, that attachment is growing ever clearer, as the state has not had good rains, or snows, since 2010. The reservoirs are getting very low.

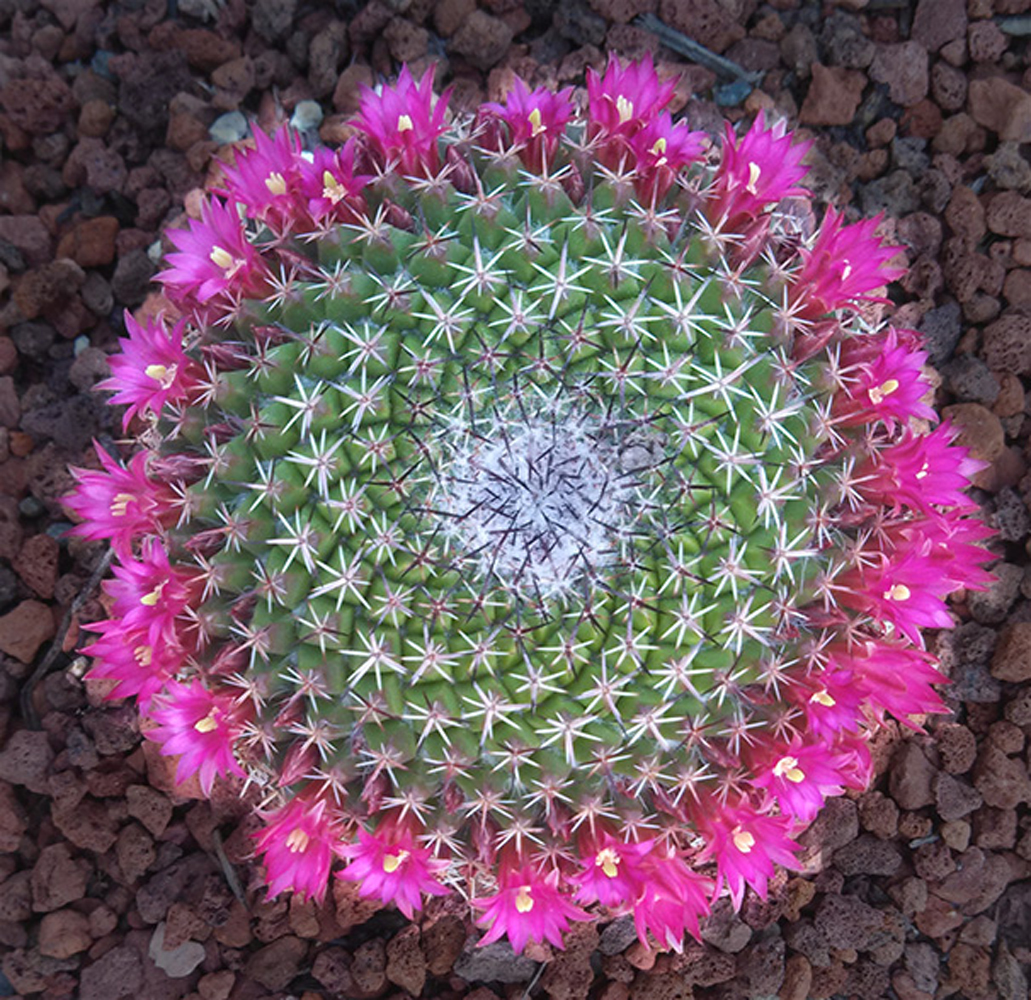

What thrives in low-water conditions? Cacti and succulents do. These plants are almost "designer-made" for the desert. They store their water smartly in stems, or fat leaves. They do so to the point it's hard to even map stems, leaves and other things we would think of as plant parts. In conditions of less and less water availability, cacti and succulents can continue to cover our gardenscapes, bringing beauty while conserving precious water resources. Botanist John Trager has been working with these remarkable plants for decades. Today, he is head curator of the Huntington Desert Garden, a place of great beauty that's a frequent tourist destination near Los Angeles. I recently asked him a few questions about his work, the Huntington and his "pets" of choice. For images of cacti, see the gallery "Drought Kill Your Garden? Consider Cactus."

Zina Deretsky: How are cacti and succulents important in the wild, and in gardens?

John Trager: Cacti fill important niches in varied habitats and serve as food plants for a whole host of organisms. Some of those feed on the stems, but more important are the flowers as sources of nectar and pollen for bees, birds, bats and other pollinators.

In some habitats, cacti comprise a significant component of the biomass. The genus Opuntia, for example, includes many species that dominate certain landscapes. []

In horticulture, cacti are becoming increasingly significant as drought-tolerant landscape plants prized for their sculpturesque architecture. In much of temperate Europe and North America, potted cacti are popular collector's items for greenhouses or windowsills, and botanical gardens often feature displays of potted specimens.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Z.D.: From where did cacti and other succulents originate?

J.T.: Cacti and succulents occur in most arid environments but are especially abundant and diverse in the dry tropics. For cacti, diversity centers around Mexico and parts of South America (Bolivia, Peru, Argentina), while other succulents are most diverse in South Africa and Mexico. Some are related to more familiar plants that are non-succulent: More than 30 different plant families are better known for their non-succulent representatives, such as Bromeliaceae (bromeliads), Cucurbitaceae (the cucumber family), Passifloraceae (the passion flower family) and Orchidaceae (the orchids). Others comprise families that are almost entirely succulent or include several hundred species of succulents, such as Cactaceae (cacti), Euphorbiaceae (spurges), Agavaceae (agaves, now included in the asparagus family) and others.

Succulents don't fossilize well, so there is scant evidence of their origins, but they appear to be recent (geologically speaking) innovations in response to drying climates. Pereskia, a genus of tropical, leafy cactus, is often cited as similar to less succulent, hypothetical precursors to the cacti we know today.

Z.D.: Cacti are so easy to propagate by cuttings (asexually or vegetatively) — you see it happen in the desert all the time: pieces fall off a cactus, take root and make new plants. If the evolutionary goal is to spread, they are already ahead of the game. Why do they also tap into the sexual route of multiplying and make the beautiful flowers that are so costly to make, energy-wise?

J.T.: Many succulents have a remarkable capacity for vegetative propagation and that can be part of the fun of growing them. Nevertheless, cacti and other succulents also propagate sexually, and as a result, often have spectacular flowers to attract pollinators (and horticulturists). The cacti also supply food for lots of animals in the desert: birds, bats, insects, bees, even lizards.

Z.D.: What is the best mix to use for a cactus in a pot or in a garden?

J.T.: There are almost as many potting mix recipes as there are growers. The primary components, however, are inorganic ingredients (course sand, gravel, pumice, perlite) and organics. The inorganics provide drainage and aeration, the organics provide moisture retention and a slow-release source of nutrients. Garden soil can be improved with these ingredients in varying proportion depending on the soil — heavier clays and silts will need more nutrients to be suitable for most succulents. Drainage can also be provided by slopes and raised planting beds.

Z.D.: What is the Huntington Garden doing in its desert garden that is important for preserving cacti?

J.T.: My role as curator of the desert collections is not only to try to keep all of our plants alive and thriving but also to keep track of all of the associated information about our collections. By maintaining a large and diverse collection of succulents, our gardens allow researchers to save considerable expense by using the wealth of species grown here rather than mounting expeditions to see plants in habitats in often dangerous parts of the world.

As with many habitats around the world, succulent habitats are often threatened by development, overgrazing, war, climate change and other pressures. So collections take on significant conservation importance as repositories of rare specimens.

The Huntington is taking its conservation efforts to another level through our plant introduction program (International Succulent Introductions), which propagates and distributes rare and unusual succulents to institutions, researchers and other interested individuals. These satellite collections can serve as living "insurance" should we lose one of our specimens. In addition, the Huntington is pioneering cryopreservation of seed and tissues to aid in long-term conservation. I work with our cryopreservation specialist and the coordinator of our tissue culture lab to select appropriate plants to target for these techniques.

Additionally, all gardens have their own unique set of microclimatic conditions, able to succeed with some plants where others can't. Horticulture trials that evaluate what can be grown in our region are of significant interest to other growers with similar climates. The nursery and landscape industries, as well as private collectors, benefit from our experiences and vice versa. The Huntington maintains collaborative relationships with members of the horticultural as well as scientific communities.

Z.D.: How does a cactus or succulent collection expedition work?

J.T.: Some floristic work— attempts to catalog the flora of a region — has been done for most regions of the world, so the first step is accessing the literature. The Huntington has an excellent botanical library that includes most of the significant publications about the plants in the regions where succulents occur. This is not to say that the world's flora has been exhaustively cataloged, but there has been a good start. In addition, the Huntington library collects ephemera, associated research materials, including the papers of noted botanical explorers. Among the most intriguing of these are often field books that read like botanical diaries of these people's travels. By perusing these pages, one can glean the types of plants collected, some of which are no longer in cultivation. Also, there may have been sightings of intriguing finds that remain to be collected and documented further.

So, some expeditions involve simply retracing the steps of those who have botanized these tracks before in hopes of finding the habitats still intact and the plants mentioned still extant. Alas, this is not always the case, as "progress" marches on with the passage of time. The time required for devastating change can be depressingly brief.

For example, the lovely pastel crème-de-menthe-colored Echeveria chazaroi was just described as new to science in 1995. In the spring of 2009 I had the privilege of accompanying a couple of echeveria specialists on an expedition to Oaxaca, the state in southern Mexico from which the species was described. When we drove by the road cut where it once grew on the rocky cliff side, we found it scraped clean of all vegetation. When later looking at the site on Google Earth, we could see that not only this road cut was affected but miles of roadside were similarly scraped as part of road widening, and to add to the devastation, the tailings were dumped off of the downhill side of the road, smothering yet more vegetation. It is not known if other populations of this species exist in the surrounding, yet-to-be-explored hills.

Roads aren't all bad. New or improved roads can provide access to areas that haven't been sufficiently botanized. These areas hold the most promise of new discoveries, but even well-trodden paths can yield new finds under the scrutinizing eye of a discerning naturalist. The potential for new insights into known species, and even more, the discovery of species new to science, is what motivates explorers to go "where no botanist has gone before."

Z.D.: Where have your collection trips taken you? What is your favorite cactus?

J.T.: I've had the privilege of travel to Baja California, Oaxaca, Namibia, South Africa and Venezuela. They were all great. My most recent trip was to South Africa this last July. The flora there is so incredibly diverse and fascinating that it might be my first choice, were it not for the greater distance and hassles of international travel. Once there, however, we had good arrangements with a local guide that made in-country travel smooth and accommodations were quite comfortable. This coming year holds the possibility of another Oaxaca trip and possibly one to Peru, home to many cacti we grow.

Funny you should ask that last question. We recently hosted a gathering of the Garden Writers of America. That was the most common question from people I spoke with. My answer is that I love all my children, so can't play favorites. But, if pressed, I will mention a favorite-du-jour, one that I've been working with recently and learned something about. This can involve a plant for which I've discovered provenance information in our records or those of others that sheds new light on where it grows and with what other plants, its cultural needs, physiology or ecological role. Another day, it might be a specimen I've been nurturing for decades that continues to thrive and is a great source of enjoyment.

Z.D.: What is the future for cacti? What would improve the outlook for the species, known and unknown?

J.T.: A recent study published in the journal Nature suggests the alarming statistic that up to one-third of all cactus species are threatened. The first step to improving the situation is habitat preservation. The range and diversity of many cacti and other succulents is well understood. However, continuing research is needed to expand that understanding, and new species and variations continue to be described and documented annually. A couple of new cacti genera have been discovered in the last few decades. Once the natural range and ecology of species are better known, rational conservation plans can be implemented to staunch the advance of habitat destruction.

Another positive approach is ex situ conservation, the preservation of documented material in cultivation. Horticulture is at its most developed state in history in regards to understanding the cultural requirements of some of these rare plants. Plants in cultivation also play a role in displays in homes, public landscapes, hobbyist plant shows and at botanical gardens (in order of increasing attention paid to conservation concerns, but all crucial in stimulating interest in and concern about these plants). Conservation biologists are also paying increased attention to size and diversity of ex situ populations needed to preserve a meaningful percentage of the genetic diversity of species, which varies from species to species.

The future of cacti, then, as with all groups of organisms, is one of preserving habitats and populations so that research can continue into the best ways to assure their conservation so that future generations can learn from and enjoy them, as well.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus