Plague in the US: Study Details 100 Years of Cases

People may think of the plague as a disease from centuries past, but more than 1,000 people in the United States have become infected with plague in the last 100 years, according to a new study.

The researchers examined cases of plague in the United States from 1900 to 2012. During that time period, there were 1,006 cases of plague, in 18 states, the study found. Patients ranged in age from less than 1 year old to 94.

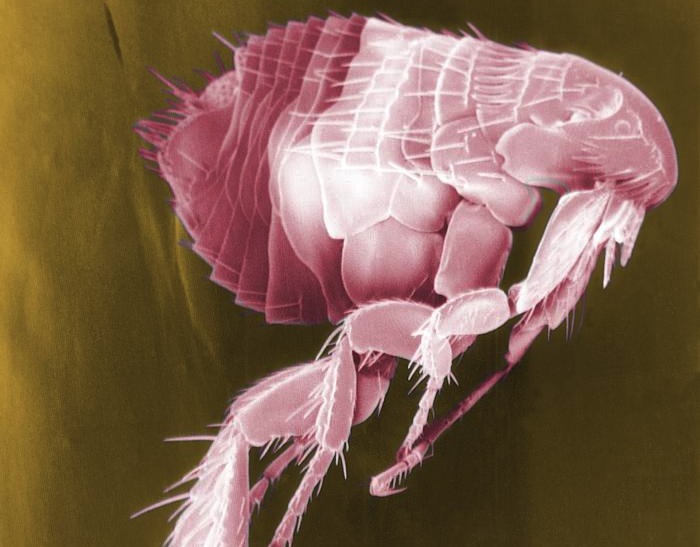

Plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, and is carried by animals such as rats, ground squirrels and prairie dogs, and their fleas. The disease is known for killing millions of people in Europe in the 1300s, in a pandemic called the Black Death. [Pictures of a Killer: A Plague Gallery]

In the U.S., between 1900 and 1925, there were nearly 500 cases of plague, mainly in port cities such as those in California and Louisiana. The disease was brought to the United States by infected rats who found their way aboard steamships, the researchers said. (The very first case of plague occurred in San Francisco's Chinatown.)

In this early period, there were several outbreaks of pneumonic plague, the only form of plague that can be transmitted from person to person. Most cases, however, were of bubonic plague, which is most often transmitted by fleabites.

Then, between 1926 and 1964, there were only 42 cases of plague (about one case per year). These cases occurred mostly inland, in California and New Mexico, with a few cases in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Oregon and Utah.

But cases rose again between 1965 and 2012, when there were 468 reported cases of plague — typically about eight cases per year, mostly in the Southwest.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This rise suggests that Yersinia pestis has become "fully entrenched" in disease transmission cycles in animals in the West, the researchers said.

The researchers were able to find information about how the person caught the disease in only about 300 of all the cases over the century. Of these, most patients were bitten by a flea. Others handled infected animals or were bitten by an infected animal. About 50 people caught the disease from person-to-person contact.

After the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s, the mortality rate from the disease dropped considerably, from 66 percent to 16 percent. People were more likely to die from plague if they were infected from an animal than a fleabite (21 percent mortality rate versus 9 percent mortality rate), the researchers found.

"The overall plague mortality rate decreased with availability of effective treatment. Nevertheless, the risk of death from plague infection is still substantial," researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention wrote in the January issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Now an endemic disease in the United States, "plague is likely to continue causing rare but severe human illness in Western states," they wrote.

People infected with plague today most often contract the disease during outdoor work, like cutting brush or chopping wood, in areas where the disease is endemic, the researchers said.

The new study may underestimate the number of plague cases, because cases may not have always been recognized or recorded.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.