Yippee Yi Yo: Study Reveals Physics of Lassos

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

DENVER - Aspiring cowboys take note: If you want to learn to lasso, you've got to start big.

The ideal lasso for rope tricks has a large loop, making up 70 to 75 percent of the total rope length, according to new physics research. Thus, the beginner's urge to start small and work up will only shoot you in the foot, according to study researcher Pierre-Thomas Brun, a physicist at the Swiss Federal Insitute of Technology in Lausanne

Other trick-rope tips include picking the right rope and finding the perfect rotation speeds for the hands, Brun told reporters last week (March 5) here at the March meeting of the American Physical Society. [Video: Trick-Roping Physics]

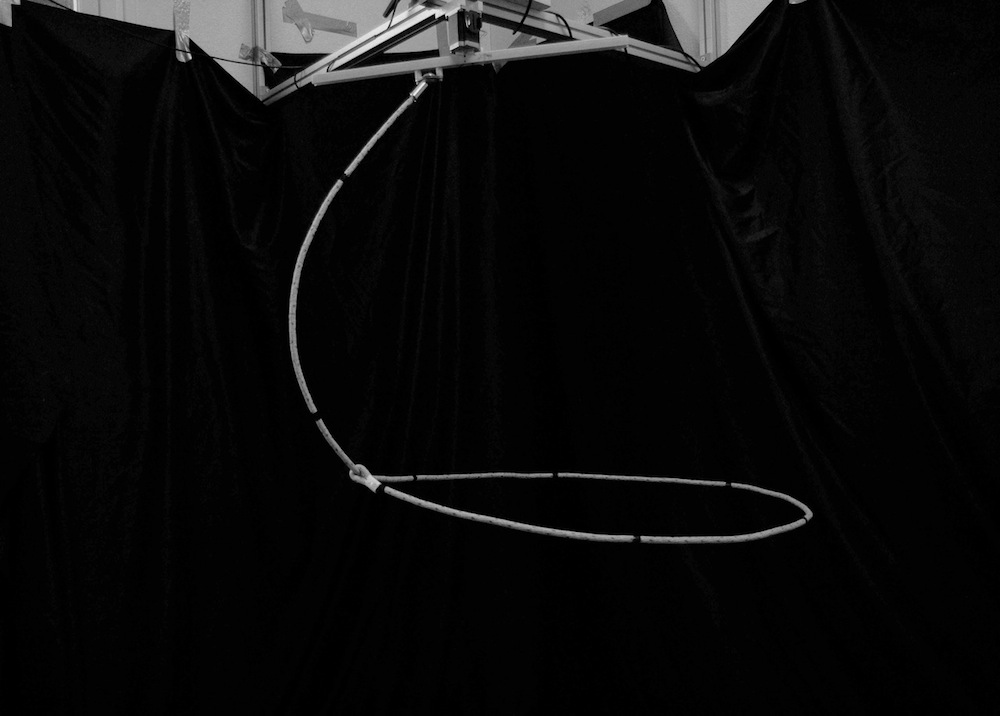

Brun researches the physics of elastic threads, a category that includes everything from DNA to human hair to transoceanic cables — and rope. He and his colleagues built a trick-roping robot, the "robo-cowboy," that spins a lasso to study the physics of tricks both simple and complicated. They also videotaped professional trick-roper Jesus Garcilazo performing complex tricks such as the "Texas Skip," which involves a cowboy creating a large vertical rope loop and jumping back and forth through it. The findings could have applications in textile manufacturing and in computer graphics.

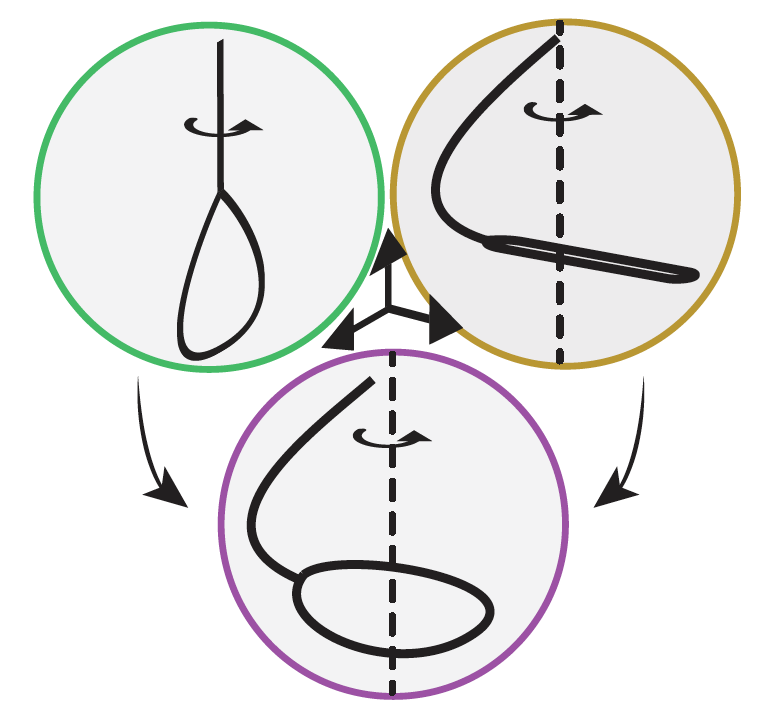

So far, Brun and his colleagues have delved into the math of the simplest rope trick, the flat loop, a horizontal spinning loop. They have found that the length of the non-looped portion of the rope (called the spoke) determines the shape of the loop when spinning. A long spoke creates what Brun calls "whirling mode," a nearly closed loop rotating horizontally. Move your hand down the spoke to shorten it, and the loop opens and flattens into a flat loop. Shorten the spoke even more and the loop continues to spin but opens vertically, looking much like a clothes hanger. The researchers dubbed this shape "the hanger."

Brun demonstrated the tricks for reporters at the APS meeting using a length of ball chain, which he recommends as a starter rope for trick-rope beginners. Further research will be necessary to understand the physics of more complex tricks, including the Texas Skip.

"Neither can I do it in real life, nor can I do it with math," Brun said of the advanced trick.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus