200-year-old Text Sheds Light on Uganda's Homophobic Bill (Op-Ed)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

In Uganda, the President Yoweri Museveni has signed into law a bill which will punish same-sex relations with fourteen years' imprisonment. Next to this, Vladimir Putin’s support of the 2013 Russian legislation proscribing the “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships”, seems to pale in significance.

These kind of things make it very easy for us in the West to consider ourselves as occupying the pinnacle of liberal tolerance. But this contrast is dangerous. One option is to look back in time for some perspective, and see what kinds of arguments for sexual liberty existed in a time that we consider ourselves well removed from.

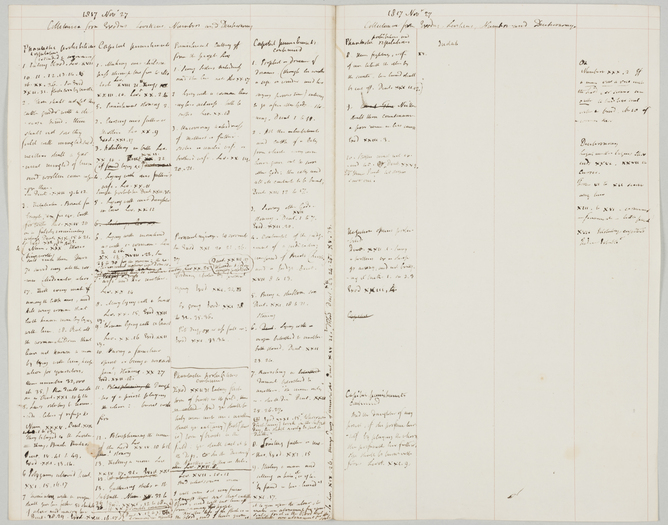

The latest volume in The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham was recently published by Oxford University Press. This text has lain tucked away in UCL’s manuscript collection since being written almost two hundred years ago, and, rediscovered, is now being published in full for the first time.

The volume in question, Of Sexual Irregularities, and other writings on Sexual Morality, contains the first systematic defence of sexual liberty in the history of modern European thought. And when Bentham’s manuscripts were catalogued in the 1930s, the following comment was added to the folder containing this discussion: “Would be prosecuted if published today.”

Written in 1814–16 as part of Bentham’s effort to overthrow the baleful influence of religious asceticism on popular morality, these essays recognise and celebrate the joy of sex. He describes sex as “the purest and most intense source of pleasure, and one equally available to rich and poor”, and rejects the question-begging label “unnatural”, which, when it means anything, means simply “uncommon”. He goes as far as to contrast the sensuality of Jesus, who not only never condemned homosexuality, but might well have indulged in gay sex, with the anathema pronounced on bodily pleasure by St Paul.

When Bentham was writing, male homosexuals, guilty of “the crime against nature”, were subject to the death penalty in England. They were being executed at about the rate of two per year. These rediscovered essays show that for Bentham, pleasure is a good thing – indeed, the only good thing.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In these writings, Bentham stressed that assuming sexual activity was consensual, a massive amount of human happiness was being suppressed, whether by the threat of hanging, by that of hell-fire, or by public condemnation, by preventing people from engaging in the activities that suited their taste. If an activity did not cause harm, then it should not be subject to punishment.

Bentham was writing after Malthus had advanced the argument that population growth always tended to outstrip food supply, resulting in misery, starvation and death. Bentham accepted Malthus’s diagnosis of the problem, but rejected his solution, that is “moral restraint”, or sexual abstinence before marriage.

For Bentham, moral restraint involved both direct loss of sexual pleasure and the pain of deliberate frustration of the sexual appetite. He did understand its justification – restraint supposedly prevented the greater pain of death by starvation of excess children. But Bentham contrasted this Malthusian trade-off between greater and lesser pains with an unalloyed good of consenting homosexual sex (and, by extension, all non-procreative sex). This delivered pleasure without the risk of pain, at least in so far it ran no risk of adding to surplus population.

Bentham did not publish these essays (and would almost certainly have been successfully prosecuted if he had). But he hoped that they might appear after his death, when legal sanctions would have held no further terror for him. Sadly, his Victorian editor John Bowring excluded not only these essays, but the entirety of Bentham’s writings on religion from his edition of Bentham’s works.

The past twenty years have seen massive strides towards the “normalisation” of homosexuality in the UK, and across large parts of the world. But prejudice persists, and in this we should remember Bentham’s response to the demand for homophobic persecution – always asking, “show me the harm”.

Bentham would be saddened, though not surprised, by President Museveni’s assertion that gay people are “rare deviations in nature from the normal”. He would see that assertion as an all-too typical example of the sort of question-begging premise from which pain-inflicting legal conclusions continue to be drawn, and to which he, as we have seen, would have given short shrift.

He would have been equally unimpressed with two other positions expressed by supporters of the Ugandan Bill, which are remarkably similar to arguments in 19th century Britain. The first is that homosexuality is “unAfrican”, a decadent practice unknown before western colonisation. The similar charge that homosexuality was “unBritish”, and had been imported by decadent foreigners, was one that Bentham dismissed as having no basis in fact.

The second equates homosexuality with paedophilia and child-abuse, on the basis that giving a dog a bad name facilitates hanging it. Again, the threat to innocence from predatory homosexuals was one that was raised in Bentham’s time, and again, he pointed out the absence of evidence for it. Perhaps we should send the President a copy of the volume – though I doubt it would change his opinion.

Michael Quinn has in the past received funding from the Wellcome Trust, the Economic and Social Research Council, and the Leverhulme Trust.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus