Why Droughts Cost More Than You Think: Op-Ed

Andy Stevenson, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) Finance Advisor and Dan Lashof, Director of NRDC's Climate and Clean Air Program contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Texas’ reputation as a small-government, big-steak, business-friendly state is beginning to wither as it continues to suffer the consequences of an extreme drought that shows little sign of abating.

The latest state water plan calls for spending $57 billion over the next half-century to guarantee that there is enough water to meet the growing needs of the state. Meanwhile, 2,000 jobs were lost earlier this year at a beef processing plant in Plainview, a town of 22,000, due to drought-related culling of herds. [Drought Reaches Record 56% of Continental US]

Overall, the costs of last year’s drought are estimated at $60 billion to $100 billion —possibly even more than Hurricane Sandy. But who ultimately ends up bearing the cost?

It turns out that $16 billion of the drought-related costs are directly borne by U.S. taxpayers in the form of large federal crop insurance losses and higher government food purchase costs.

Scientists will continue to debate the roles that climate change and natural variability played in last year’s drought — both undoubtedly contributed — but with the concentration of carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere rapidly approaching 400 parts per million, more than 40 percent above natural levels, it’s clear that we need to start budgeting for the high costs of more extreme weather. That’s because the extra heat trapped by carbon dioxide, methane and similar pollutants evaporates water faster when weather is dry and also leads to more intense storms when weather is wet. [Perfect Storm: Climate Change and Hurricanes]

When it comes to drought, the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC), administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)'s Risk Management Agency, ends up footing a big part of the bill. The FCIC allows farmers growing corn, cotton, soybeans and wheat to purchase two main kinds of insurance that have been affected by the drought: yield-based insurance that pays out relative to the farmer's "normal" historical output and revenue-based insurance that pays out relative to a projected price and yield.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

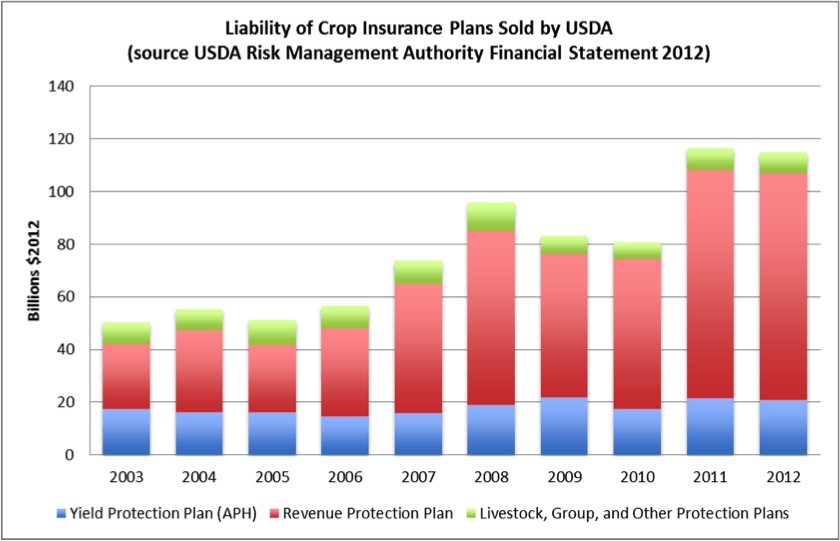

While both protection plans have increased in recent years, the face value of revenue protection insurance policies has risen by more than a factor of four over the past decade, accounting for $86 billion, or 75 percent, of the FCIC’s total liabilities of $115 billion.

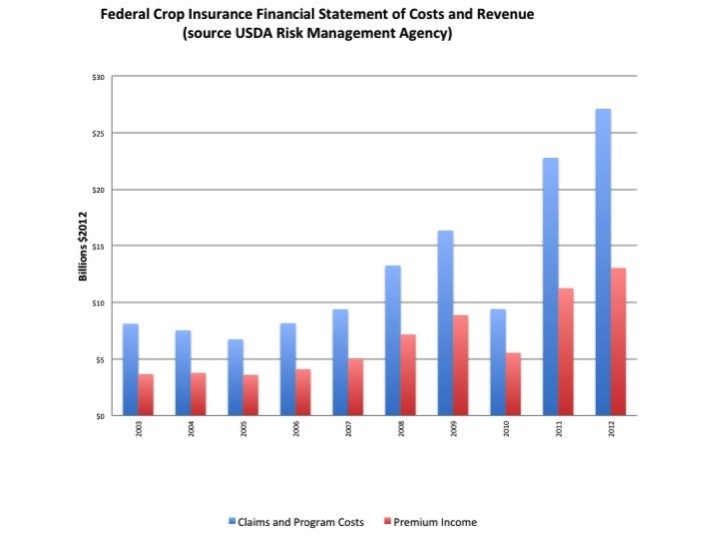

As the severity and duration of droughts has intensified over the past decade, the FCIC program has suffered from the same problems plaguing the National Flood Insurance Program — income from premiums is too small to cover rising claims and program costs. In 2011 alone, lower crop yields related to drought, rising incidents of insects and disease, and bad weather caused the FCIC to lose $11 billion, with losses this past year estimated at $14 billion.

In addition to the losses suffered by the federal insurance program, the U.S. taxpayer is also expected to see the drought increase the costs associated with government-sponsored food programs. These impacts are expected to hit government budgets in 2013 due to the 9- to 10-month lag between prices on the farm and prices at the grocery store.

Using USDA Economic Research Service estimates, last year’s drought is expected to increase our grocery bills in the U.S. by an inflation-adjusted 1.8 percent, or $24 billion in 2013. While most of these costs are being paid directly by U.S. consumers, the government is expected to cover about $2.3 billion of these costs directly as the country’s single largest purchaser of food.

When these higher food costs are added to the estimated $14 billion losses by the FCIC, total taxpayer losses from this past year’s scorching weather are expected to total $16.3 billion.

These costs contribute to a climate disruption tax that we are already paying today to deal with a changing climate. By comparison, the costs of curbing the pollution responsible for climate change is a fantastic bargain that we can’t afford to pass up.

Read Stevenson and Lashof's most recent Op-Ed: Why You Are Paying for Everyone's Flood Insurance

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.