Teaching Science Policy With Creative Nonfiction

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

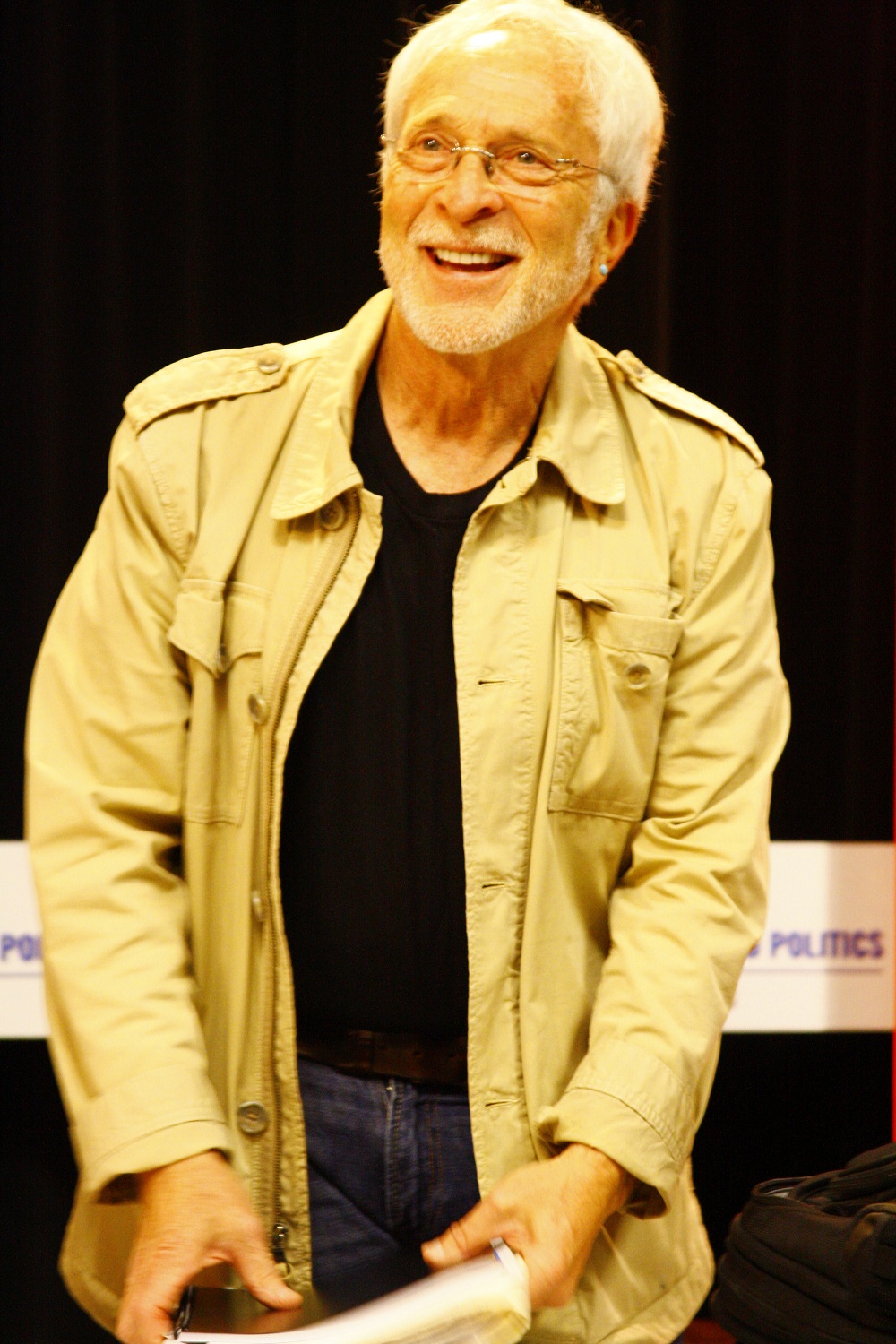

Lee Gutkind is the founder and editor at Creative Nonfiction magazine and the author of a number of creative nonfiction books including Almost Human: Making Robots Think — featured on the Daily Show with Jon Stewart — and the award-winning Many Sleepless Nights: The World of Organ Transplantation.

Below, Gutkind describes the creative nonfiction movement and the field’s potential to change public thought.

A science policy book on the New York Times bestseller list for more than two years — one that is being made into an HBO movie produced by Oprah Winfrey — who ever heard of such a thing? Yet, that’s what happened to science writer Rebecca Skloot’s creative nonfiction bestseller, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

Skloot was my student at the University of Pittsburgh and her writing techniques — and incredibly successful book — serve as a model for To Think, To Write, To Publish, a program of intensive, two-day workshops at Arizona State University. The workshops brought together next generation of science and innovation policy scholars with rising communicators, writers, and editors, who, together introduced new ways of understanding established policy concepts through the ancient art of storytelling.

The program has been expanded and extended for 2012 with two four-day workshops and year-long mentoring. We are in fact already seeing applicants — scholars and writers both. More information is available at www.thinkwritepublish.org.

Why write

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There are many motivations behind the program and its potential to represent a game-changing and culture-changing approach, foremost being the challenge of communicating complicated ideas to the general public.

Communicating science — and science and innovation policy, the practices that form the guidelines and principles concerning the social and ethical dimensions of the work of scientists and innovators — to the general public has never been more vital. The world is becoming more complex by the day, and to succeed in business, education, economics — even politics — people have come to realize they should have, at the least, a working knowledge of genetics, robotics, physics biology and a host of other science and technology fields.

But, science is foreboding. It often demands a different mind-set and an understanding of processes and terminology that seem foreign and elusive. Communicating science and innovation policy creates even more complexity and challenges, beginning with the public's incomplete understanding of what science and innovation policy actually is. The concept of "policy" sounds foreboding and academic, something far beyond the general public's need to know or care, and scholars often are not experienced, or even comfortable, talking to the general public and explaining what they do.

Connecting with the public

When I joined the Consortium for Science Policy and Outcomes at Arizona State, this was one of the challenges I wanted to address. How can science and innovation policy scholars connect with the general public, make them aware of what policy scholars do and how important it is to think ahead about this subject? I was convinced that the way to succeed in doing this was through storytelling.

I helped pioneer the creative nonfiction literary genre, spawning a movement that has made creative nonfiction among the fastest growing genres in the publishing arena, and now including related fields, such as narrative law, narrative medicine, narrative science and narrative history. In the time since I helped to start the first Master's of Fine Arts program in creative nonfiction at the University of Pittsburgh in 1993, there are now more than 100 graduate level creative nonfiction programs throughout the world.

So what is creative nonfiction, exactly? In brief, it means: "true stories, well told." Essentially, the idea is to communicate facts in a more cinematic way, to introduce real characters behind the facts, to tell a true story with action and excitement to communicate information about a subject in a more compelling way than would generally be possible with straight exposition or traditional journalism.

Collaborative work

My consortium co-director David Guston — who is the project’s co-principal investigator — and I realized that the multifaceted science and innovation policy communications problem required a unique, collaborative approach. We established "To Think, To Write, To Publish" to bridge the multiple communications gaps by establishing 12 collaborative, two-person teams that paired next-generation science policy scholars with next-generation science writers. Together, they were tasked with learning creative nonfiction and narrative techniques and writing a creative nonfiction essay together, utilizing the scholar's research.

Writers and scholars were recruited independently with nationally circulated announcements from Consortium for Science Policy and Outcomes and the Creative Nonfiction Foundation, which publishes the magazine "Creative Nonfiction." For the 12 communicator positions, there were 177 applicants including journalists, creative nonfiction writers, publishers, playwrights, poets and teachers, and for the 12 science and innovation policy scholars, we selected from a pool of more than 40 applicants.

On the first day, the writers attended an immersion workshop in the techniques and craft of the genre, learning how to utilize creative nonfiction storytelling techniques to reach a general audience and make policy more accessible. On the second day, the writers and scholars came together and prepared a presentation for a third constituency — editors and literary agents. Representatives were on hand from Smithsonian Magazine, Nature, Creative Nonfiction, and Issues in Science and Technology, published by the National Academy of Sciences. An editor-publisher from Simon & Schuster and a literary agent from Folio Management were also part of the editorial panel.

In a "pitch slam," the collaborators presented two-minute "pitches" outlining the subjects they intended to write about, the angles they would take, and the stories they envisioned. The stories combined the scholars’ research and the communicator’s ideas about how to frame the research in story.

More work

Kevin Finneran, editor of Issues in Science and Technology, explained the effort well: "The goal is to develop a way to make science policy more accessible and engaging to a large audience. The method is to incorporate the policy analysis into a large narrative structure because, though this is hard to believe, some people would rather read a compelling story than a meticulously organized piece of rigorous academic argument."

Since the first workshop in 2010, we have been inspired to see a subtle but growing impact within — and beyond — the consortium and Arizona State, including graduate students contemplating narrative dissertations, my ongoing work with psychologists, psychiatrists and former mental health patients to write stories of recovery in Arizona, and presentations about the program across the country. One participant has even started an online creative nonfiction social action journal and another has become publisher of a medical science-oriented book series.

Issues in Science and Technology has since accepted for publication the first group of four successful essays — the first time the journal published creative nonfiction and narrative.

Editor's Note: The researchers depicted in Behind the Scenes articles have been supported by the National Science Foundation, the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Behind the Scenes Archive.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus