Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Earth probably became a "synestia" for a brief period about 4.5 billion years ago, according to a new study.

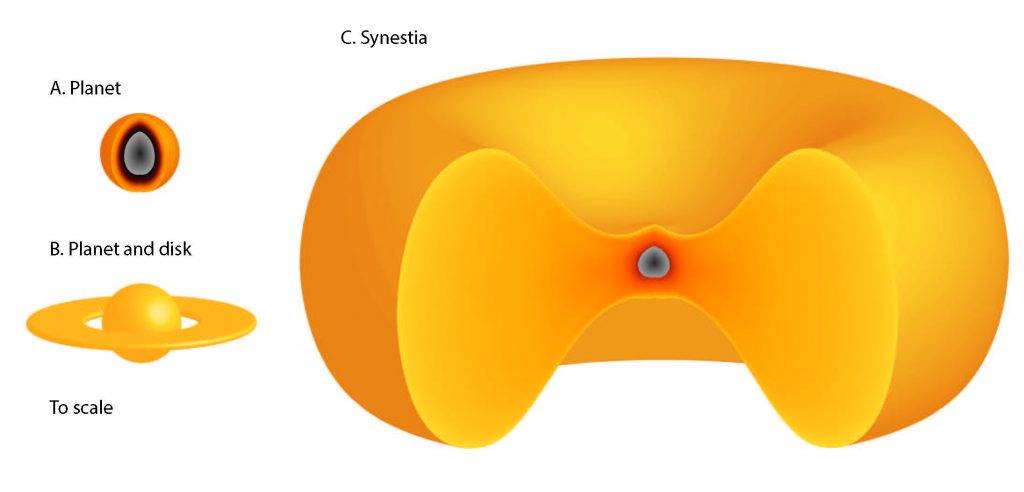

That's the term for a newly proposed cosmic object: a huge, hot, donut-shaped mass of vaporized rock that results from the collision of two planet-size bodies.

Astronomers think Earth endured such an impact shortly after the planet's birth, slamming into a Mars-size object known as Theia. (This smashup — or series of smashups, as one recent study posits — also resulted in the creation of Earth's moon, scientists believe.)

"We looked at the statistics of giant impacts, and we found that they can form a completely new structure," study co-author Sarah Stewart, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Davis, said in a statement.

Stewart and lead author Simon Lock, a graduate student at Harvard University, modeled what happens when rocky worlds about the size of Earth crash into other large bodies that are moving, and spinning, relatively fast. The researchers' simulations suggest that the most violent encounters would produce synestias, putative structures that look like gigantic red blood cells.

Previous studies have posited that such impacts might produce a debris ring around a planet. But a synestia is a far bigger and weirder object; it is made mostly of vaporized rock and has no solid or liquid surface, Lock and Stewart said. (The name synestia, incidentally, comes from "syn," Greek for "together," and "Estia," the Greek goddess of structures and architecture.)

Synestias — if they exist — are short-lived objects. Earth likely stayed in the synestia phase for just a century or so after the collision with Theia, according to the new study. The synestia-Earth then lost enough heat to condense back into a solid object, the thinking goes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At the moment, synestias are hypothetical objects; nobody has ever seen one. But astronomers may be able to spot them in alien solar systems, Stewart said.

The new study was published online May 22 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus