In Photos: Lost Prehistoric Code Found in Mesopotamia

Peering inside clay balls

Scientists are using CT Scans and 3D modelling to peer inside sealed clay balls, often called "envelopes" by researchers. Only about 150 intact examples survive worldwide today and they contain, within them, tokens in a variety of geometric shapes. Their purpose was to record economic transactions but how exactly they did this, before writing was invented, is unknown. The examples the team scanned were excavated from the site of Choga Mish, in western Iran, in the late 1960s and are now at the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute. They date back about 5,500 years, roughly two centuries before the invention of writing. The exterior of each ball contains an "equatorial" seal running down the middle and, often, two polar seals running above and below.

Valuable clues

The seals on the exterior may provide valuable clues as to how the balls were used in prehistoric times. Christopher Woods, a professor the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute, notes that the “polar” seals tend to be repeated more frequently and contain simpler geometric motifs. The seals in the middle, on the other hand, tend to be unique and contain more elaborate mythological motifs. He hypothesises that the seal in the middle represented the “buyer” and the polar seals the “seller” or distributor and perhaps third parties who were involved in the transaction or served as witnesses. After an important transaction was complete he suggests that the clay balls were created as a receipt for the seller so they could keep track of what was expended.

How we know

The reason scholars know that these clay balls were used for economic transactions is because this example, excavated at the site of Nuzi in Mesopotamia, dates to about 3,300 years ago, long after writing was invented. It contained 49 pebbles and a cuneiform contract commanding a shepherd to care for 49 sheep and goats. How these balls would have communicated information like this before the invention of writing is a mystery which the researchers shed light on by scanning intact examples.

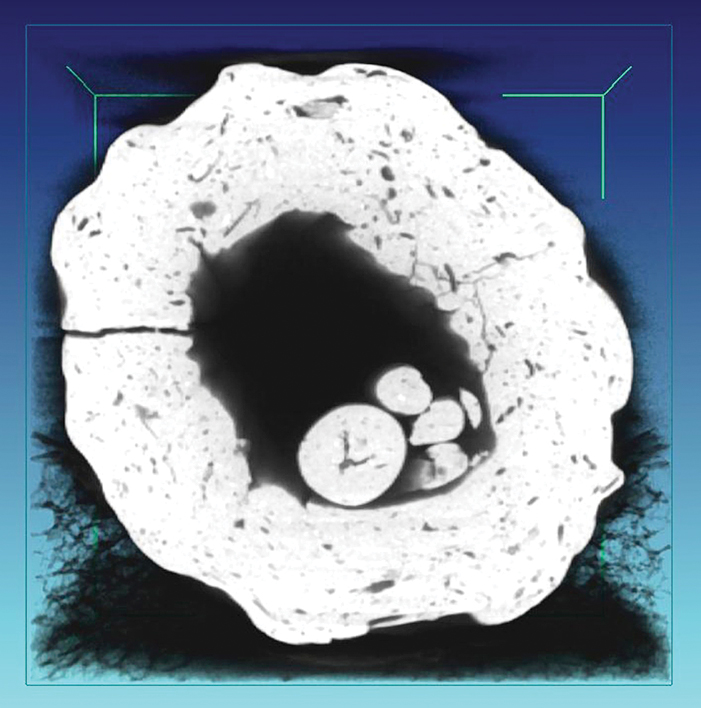

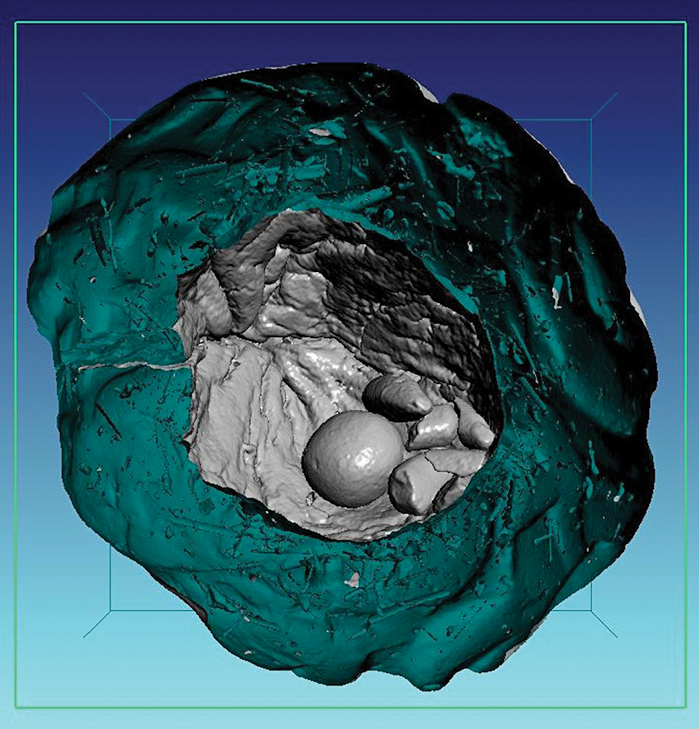

A peek inside

At North Star Imaging in Minnesota multiple high resolution scans were made of each of the balls, an image of which is seen here. These images were then turned into dissectible 3D models at Kinetic Vision in Cincinnati.

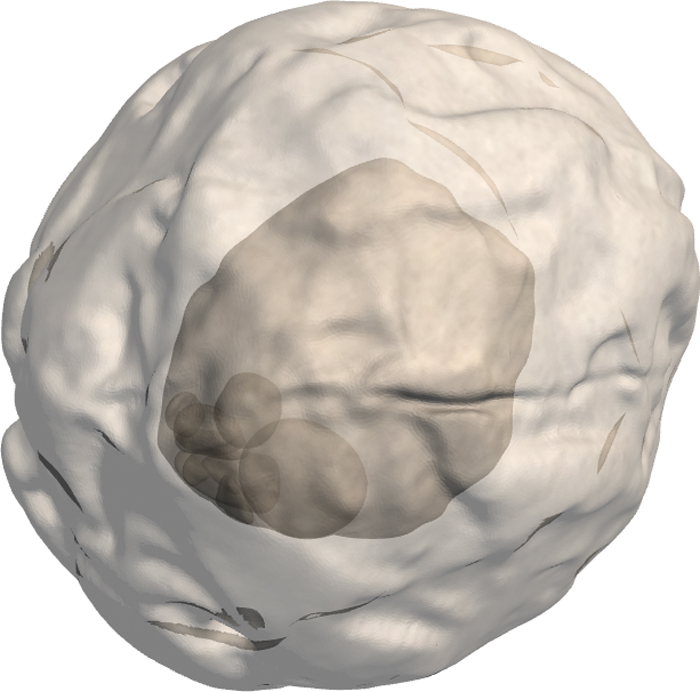

Detailed views

The CT Scans and 3D modelling allowed for incredibly detailed views of the clay balls, and their contents, to be created, allowing researchers to analyze them layer by layer. Christopher Woods said that they can get more information by using these non-destructive techniques than they could by breaking open the balls.

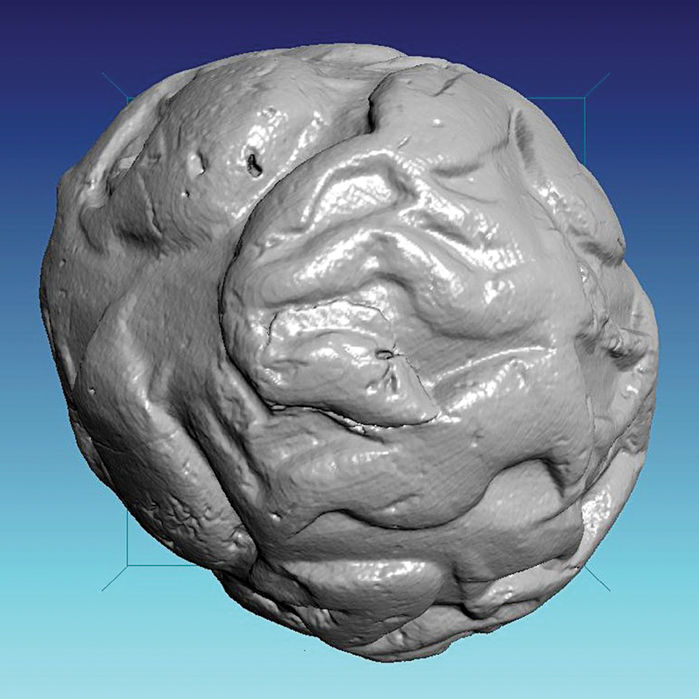

Better view of the outside

Even the exterior of the balls, which were already visible, could be analyzed in greater detail.

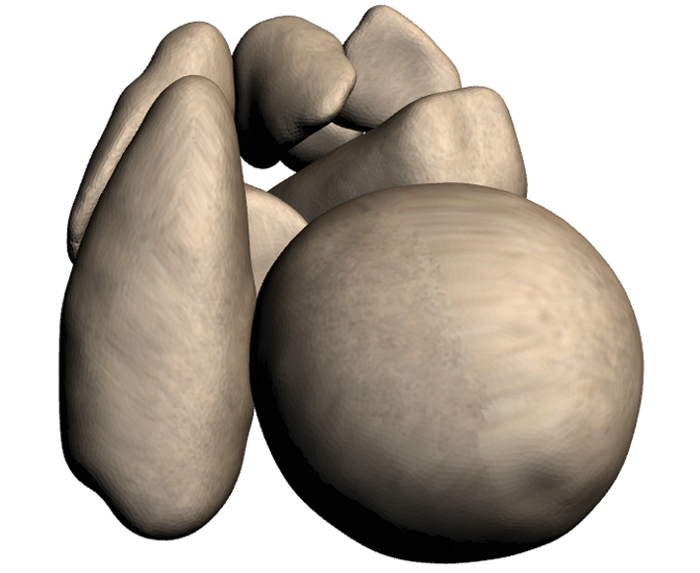

Greater clarity

The scientists were able to see the shape and markings of the tokens, within the balls, in great detail. In this image a “false color” is applied to the shell of a clay ball. After scanning more than 20 clay balls the scientists could identify 14 geometric shapes, including spheres, pyramids, ovoids, lenses and cones, within them.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

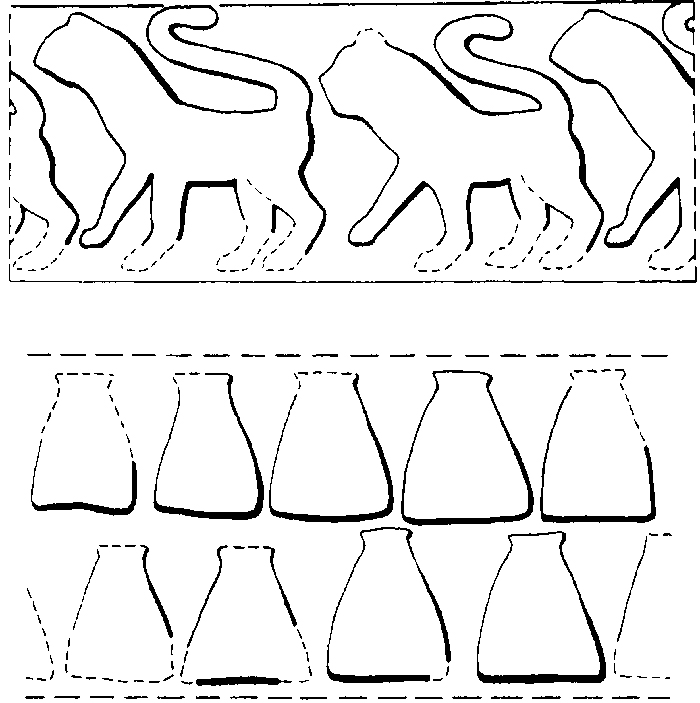

Geometric translation

Christopher Woods hypothesises that, rather than whole words, these tokens would have conveyed numbers connected to a variety of metrological systems used in counting different types of commodities. A sphere, for instance, could mean a certain unit (ie- 10) that was used while counting a certain type of commodity.

Prehistoric communications

The information the team obtained may make it possible, in time, to crack the prehistoric code. Woods points out that we know how numbers and metrical units were depicted 200 years later when writing was invented. If people in prehistoric times depicted these numbers and units in a similar way, using the different shapes of the tokens, than it may be possible to gain some understanding of what they were trying to communicate. This image shows a clay ball, with tokens, found broken at the site of Choga Mish.

Putting the pieces together

The highly detailed information about the different ball layers allow scientists a chance to piece together how they were put together. This photo shows Brian Zimerle, the Oriental Institute’s preparator and ceramicist, creating a modern day clay ball with tokens.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus