Untangling the Source of Ouch and Itch

Many of us have experienced the sting of a bad sunburn and the itchy, peeling skin that follows. For decades, scientists suspected that pain and itch were the same thing, only expressed at different intensities: Itch was just light pain, and pain was strong itch.

Scientists have been trying to better understand how these sensations occur on a cellular level. Recent studies funded by the National Institutes of Health show that pain and itch stem from a complicated process involving many types of neurotransmitters, chemicals that transfer nerve signals to the brain, and receptors, cell surface proteins that accept those signals. A major goal of this line of research is to find better ways to tackle chronic pain and itch conditions, which often persist despite use of soothing medicines.

Defining Pain and Itch

Pain and itch are both forms of nociception, the sensing of danger through stimulus from the environment. At a basic level, pain tells the body that there either has been an injury or that one is imminent. Nociception is the reason why we feel a burning sensation when we get too close to a flame. Itch, clinically known as pruritus, signals that there is an irritant or potential toxin around.

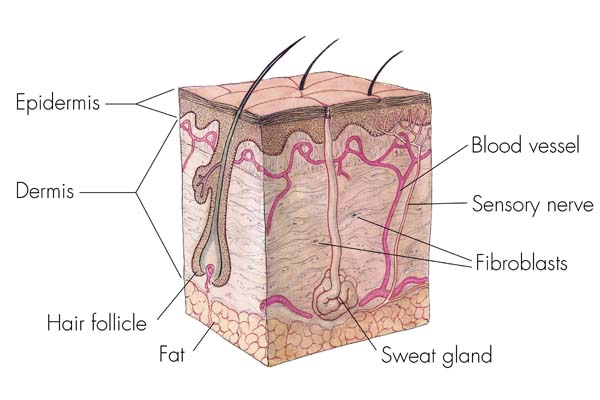

In both cases, the skin is vital to signaling. Cells called keratinocytes live at the base of the epidermis, the surface layer of the skin, and send sensory signals to nearby nerve endings. If skin were a stone wall surrounding a town, then keratinocytes would be the watchtowers that alert the townspeople about approaching intruders. The nerve endings transmit the signal through circuits of multiple nerve cells toward the brain.

But pain is not limited to the skin. The same pain receptors exist on nerve endings inside the body, producing the sensation of an achy muscle or stomach cramp. That's not the case with itch receptors. They only go as far inside the body as the mucous membranes, such as inside our nostrils or throat. This is why our internal organs never seem itchy. If they did, imagine how hard they'd be to scratch!

Pain and itch can come about in different ways. Itch, for example, can be brought on by chemicals called histamines. Histamines are a critical part of the allergic reaction that we feel with a mosquito bite or with hives. Histamine-mediated itch can be relieved with an antihistamine. But the majority of chronic itch doesn't involve histamine, making it difficult to medicate. In fact, that sort of histamine-independent itch is a common side effect of pain medications such as morphine.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists took this connection between pain and itch as another clue that the two are related, but they still weren't sure whether itch was simply dulled pain or a distinct sensation. They started looking for answers in the nerve cells.

Finding Pain and Itch

One answer comes from scientists at Johns Hopkins University. The researchers found two families of receptors on nerve cells that receive signals from keratinocytes: TRP receptors mediate pain and itch, and Mrgpr receptors mediate histamine-independent itch.

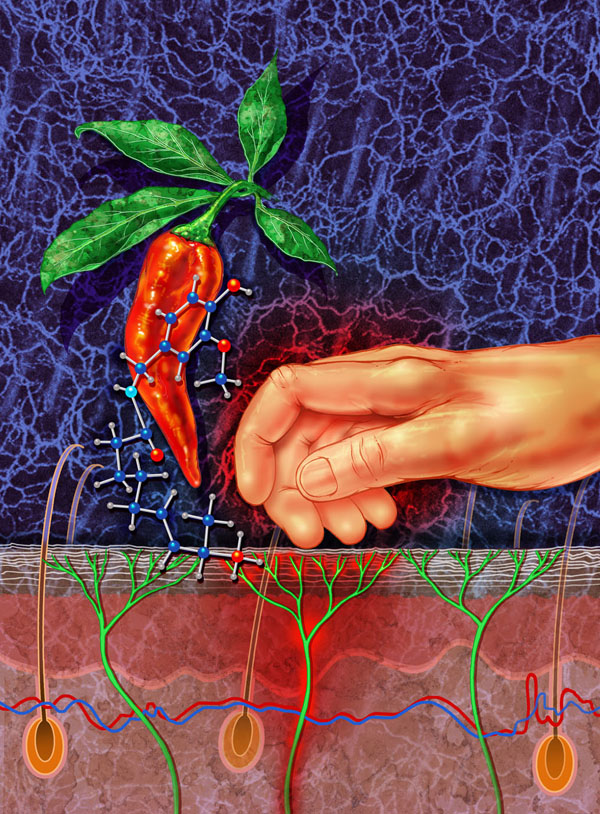

Scientists made these findings by turning off different types of receptors in mice, which have a similar nervous system to humans. By exposing the mice to chloroquine, an antimalarial drug that can cause itching as a side effect, and capsaicin, the "hot" compound in spicy peppers, they could tell what the mice sensed.

"If the mouse felt an itch, it would scratch behind its ears with its hind leg," says Xinzhong Dong, who led the study. "When it felt pain, it would rub its cheek with its front leg."

Mice lacking an Mrgpr "itch" receptor specific to chloroquine could feel pain but not itch. Mice that didn't have a TRP "pain" receptor that responds to capsaicin actually found capsaicin itchy instead of painful.

Dong explains that these findings indicate that neurons containing only the TRP receptor process pain sensation. On the other hand, neurons containing both the TRP receptor and the Mrgpr receptor transmit itch signals.

The results also suggest that pain circuits can inhibit itch circuits, so only one signal is sent at a time — explaining why pain and itch rarely happen simultaneously.

Today, researchers are pursuing drug compounds that directly block pain and itch receptors to deliver more targeted relief with fewer side effects.

The research reported in this article was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health under grants R01GM087369, R01NS054791, P01NS047399, R01NS014624 and R01NS070814.

This Inside Life Science article was provided to LiveScience in cooperation with the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Learn more:

Fact Sheets on Anesthesia, Burns and Trauma

Video: The Body's Response to Traumatic Injury

Also in this series:

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus