Your last chance to watch Venus cross the face of the sun is less than a month away.

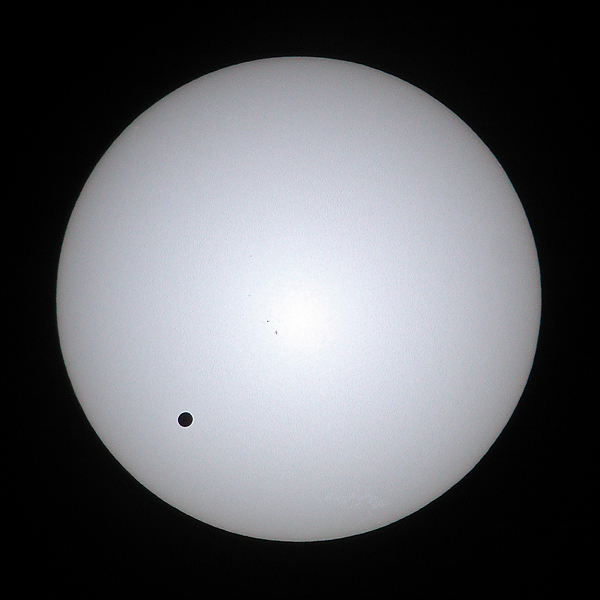

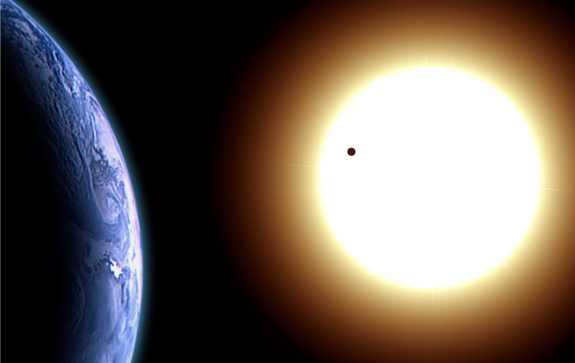

This rare event, known as a transit of Venus, will take place on June 5 for Western Hemisphere observers, though it will be June 6 local time for skywatchers in the Eastern Hemisphere. Over a seven-hour span, Earth's so-called sister planet will trek across the solar disk from our perspective, appearing in silhouette as a slow-moving tiny black dot, weather permitting.

Venus transits occur in pairs that are eight years apart, but these dual events take place less than once per century. The last one happened in 2004, and the next won't come until 2117.

"Only six such events have occurred since the invention of the telescope," said astrophysicist Sten Odenwald, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., in a statement. [Venus Transit of 2004: 51 Amazing Photos]

Historical significance

Venus transits hold a special place in astronomical history. In the 18th century, scientists and explorers traveled around the world to watch them, in an effort to calculate the size of our solar system.

The idea came from astronomer and mathematician Edmond Halley, of comet fame. In the 1700s, scientists knew the relative size of the solar system — they knew that Jupiter orbited the sun about five times farther out than Earth did, for example — but its absolute dimensions remained a mystery.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1716, Halley suggested a way to get the answer: Send teams to different spots around the globe to observe a Venus transit. By noting the precise start and stop time of the transit from various locations, researchers could calculate the Earth-sun distance using the principles of parallax. With that information in hand, the scale of the rest of the solar system would follow.

An effort was mounted for the 1761 Venus transit. It failed due to bad weather and various other factors, but observers did witness a fuzzy halo around the planet that they interpreted, correctly, to be evidence of an atmosphere.

A repeat try in 1769 — which sent famed British explorer James Cook to Tahiti and other teams to a total of 76 points around the world — went more smoothly, but still came up short. In the end, scientists got the data they needed by photographing the next pair of Venus transits, which came in the 19th century.

Scientists are still interested in Venus transits today, though for different reasons. NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory spacecraft, for example, will watch the June 5/6 event to help calibrate its instruments and to learn more about Venus' atmosphere, researchers said.

And NASA's Hubble Space Telescope will observe the transit using the moon as a mirror, to test out a technique that could eventually probe the atmospheres of faraway alien planets.

Observing tips

The coming transit is also a seminal event for skywatchers, since very few folks alive today are likely to be around to see the next one in 2117.

At least part of the June 5/6 transit will be visible from most places around the world. But if you want to see the entire seven-hour event, you may have to jump on a plane or gas up the car. The whole transit will be widely visible from eastern Asia and eastern Australia, New Zealand, the western Pacific, Hawaii, Alaska, northern Canada and most of Greenland.

Warning: NEVER look at the sun with your naked eye, binoculars or a telescope. Serious and permanent eye damage, including blindness, can result.

To safely observe the sun, you can buy special solar filters to fit over your equipment, or welder's glasses to wear over your eyes. But the safest and simplest technique is to watch the transit indirectly with the solar projection method. Use your telescope, or one side of your binoculars, to project a magnified image of the sun’s disk onto a shaded white piece of cardboard.

The image on the cardboard will be safe to view and photograph. But make sure to cover the telescope's finder scope or the unused half of the binoculars, and don't let anybody look through them.

NASA also plans to air live footage of the transit taken by various instruments. Check the space agency's website (www.nasa.gov) for specifics as June 5 approaches.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.